Few know their names…but everybody knows the sound that they created. In the documentary Standing in the Shadows of Motown, some of the greatest artists of Twentieth Century's pop music scene like Steve Wonder, the Supremes, and the Temptations paid homage to a group of little-known studio musicians known collectively as The Funk Brothers. This unlikely collection of musicians comprised Motown founder Berry Gordy and Hitsville USA's in-house studio band, providing the background composition that made Motown and many of their musical artists into recording legends. Only recently has this collection of talented white and black troubadours finally gotten their due – thanks in large part to the research and work of Philadelphia producer/author Allan Slutsky and his book Standing on the Shoulders of Motown: The Life and Music of Legendary Bassist James Jamerson – much of the focus of The Funk Brothers has been on their collective musical association and their enigmatic yet troubled leader and bass player James Jamerson. While Jamerson's contributions to Motown's early history cannot be understated, there is another interesting element of The Funk Brother's story in that all members of this iconic backing band brought their own stories and musical upbringings to the table and each deserves to have their stories told in their entirety.

One such member of the Funk Brothers has a distinct tie to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the rough quarters of the quarry company town of Billmeyer in Coney Township, Lancaster County. This roadmap of early musical influences runs from the halls of a local high school that has vanished from the map, to the churches and civic halls of nearby, mostly white, Anglo-German communities who had never really been exposed to the musical traditions of American Americans, all the way to the other side of the world with the US Air Force, before finally ending up at Berry Gordy's Studio A on 2648 West Grand Boulevard in Detroit. There, guitarist Robert Willie White served as a major part of The Funk Brothers' iconic guitar trio, but his contributions to popular music are far more significant. Through his unique style of play and his talent for clarity of pitch, White provided some of the most iconic guitar riffs in popular music history as he drew from his own styles developed over a decade of musical education. While White himself did few interviews about his life, and accounts of his early years prior to 1960 when he joined Motown are limited, the few clues that do exist paint an interesting picture of a talented young musician destined for bigger things. His personal musical journey fits like fingers to frets in the larger historical context of an evolving African-American music scene: the influence of traditional gospel of the late 1940s and early 1950s, the marketing power of jazz as well as commercial rhythm and blues in the mid-to-late 1950s, and the evolution of mainstream pop and soul of Motown via the growing recording and record industry in the early 1960s. These three-phased evolutions in popular music influenced the musical growth of White as he went from amateur to professional musician. This article will also pay homage to White's humble upbringing and relatively unknown status as a musical "favorite son" of Pennsylvania and Lancaster County, which has (sadly) been mostly forgotten when it comes to the collective history of the area.

Preface: The White Family’s Arrival in Billmeyer

The story of Robert W. White begins with his father, Willie Franklin White, the family patriarch who contributed to his son's future music development by bringing his family to Lancaster County. Born in Louisa, Virginia, in 1912, Willie White grew up in a small working-class community in the Virginia triangle of Fredericksburg, Richmond, and Charlottesville. Census records show that Willie immigrated north in the early 1930s sometime during the midst of the Great Depression. Like many American men (black and white) during that time, Willie was probably searching for better economic prospects in an era of epic financial decline. Heading north seemed like a logical answer, so Willie White joined the millions of other families making the pilgrimage to the economic sanctuaries of New York City, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Detroit. However, the so-called later portion of the Great Migration that had characterized this era of African-American history from the 1910s through the 1930s had slowed to a trickle by the time Willie White was making his journey. Because of the economic troubles of the nation, as well as the realization that racism was no less in the North than it was in the South, young African-American men did not find their fortunes as readily in major urban areas like they had expected. So, what drove Willie White to pack up and head north? Perhaps it was the influence of another African-American man, one who understood the destitute nature of families in Willie's situation and offered the opportunity for a better life.

In his article for Pennsylvania Heritage Mennonite Magazine, local historian Dale Good wrote about a unique character who brought economic opportunity to African-American families and considered Lancaster County his home base. His name was Harvey V. Arnett. According to Good's research, Arnett was a man who in many ways mirrored Willie White's story. Born in the same Virginia community as Louisa and Willie White, Arnett was the son of former slaves and had moved north to the company town of Billmeyer in Conoy Township, Lancaster County, near where present-day Bainbridge, Pennsylvania is located. His reason for moving was also motivated by economics as his wife's brothers had migrated to Billmeyer years prior seeking a better life and found it working for the J.E. Baker Company of York, Pennsylvania, that owned and operated the massive limestone quarries. Founded in 1889 by York businessman and banker John E. Baker, the J.E. Baker Company started as a Wrightsville company leasing quarry lands and kilns to the iron and railroad industry. By the late 1890s, the company had grown considerably and began to invest in new quarries both inside and outside of Pennsylvania. By 1896, the Billmeyer Quarry had opened, offering employment opportunities not just for local men but also for scores of African Americans and newly arriving immigrants from Eastern Europe. Arnett would rise, according to Good, to a place of economic prominence in the Billmeyer community, serving as a foreman (officially) and as a recruiter of labor for J.E. Baker's Billmeyer opportunists. Good believes that, between the 1910s and the 1930s, Arnett traveled back to his native Virginia often to visit family and to recruit from an available workforce of men. To do so, he showcased his own success story with the J.E. Baker Company and the promise of economic opportunity to anyone who followed him. In many cases, Arnett paid for his new co-worker's moving expenses. Census records of the time, according to Good, also seem to bear this out as the African-American communities in Billmeyer and other local areas of Lancaster County saw African-American populations skyrocket to over three 300 during Arnett's recruiting period. World War I and the need for "dead burned" dolomite as a substitute for European imported magnesite in the production of steel may have also helped in this regard, but the sight of a "a large, well-dressed and impressive-looking Black man," as Good described Arnett, may have left more of a lasting mark on men like Willie Franklin White to come north and seek their fortunes in Lancaster County.

Willie White makes his first appearance in Billmeyer between 1935 and 1940, towards the end of Arnett's career. White is listed on his World War II draft card and the 1940 census documents as a twenty-eight-year-old man of average height and build (5'9" at 169 pounds) with a dark complexation, black hair, and brown eyes. In 1940, census data shows that Willie White's occupation is listed as a laborer in the Billmeyer quarry where he made a little over $900 a year and lived in a rented home on Conoy Road with $3.50 a month in rent. He is also listed as the head of a growing family. His wife, Margaret C. White, was young in 1940 (only eighteen) and is originally from Ohio. It is unknown how she and Willie White met and fell in love, but a theory could be that she was drawn to Billmeyer by the pull of her sister, M. Irene White, who also happened to be married to Willie's older brother Ison. The White family also lived right next door to their close in age in-laws in the laborer quarters known as "Society Row." While the story may sound like a Hollywood screenplay – that two sisters would end up marrying two brothers – in a small community like Billmeyer with a cloistered African-American population, it may have been more common than some might realize. Listing his occupation on the 1940 census as driller for the quarry, Ison White also worked for the J.E. Baker Company. M. Irene White's obituary appears in an October 1954 issue of a local newspaper known as the Elizabethtown Chronicle, and she was buried alongside other employees of the J.E. Baker Company in the Bainbridge Cemetery. Both Willie and Ison would not serve overseas in World War II as both of the local newspapers in the area, the Elizabethtown Chronicle and the Lancaster Intelligencer, list them as "2-B Candidates – Necessary for War Production," which meant their labor in the Billmeyer quarry was seen as more vital to the war effort than their potential service on the battlefield. Willie White also had four children in his household by 1940 – seven-year-old Margaret, five-year-old Floyd, three-year-old Robert, and two-year-old Melvin. Early in the conflict, men with large families were not called to military service, so this fact might also be an explanation as to why Willie White did not serve. The family continued to grow with the years. In 1941, William White was born, joined later by two more daughters, Lola and Irene. Another daughter, Joyce Ann White, only lived three months, following a nine-hour bout with meningitis. Her grave is listed as in the Bainbridge Cemetery according to her death certificate. However, the grave itself cannot be located on any of the cemetery's registry or other burial records. This family roadmap provides a clear picture of the economic and social surroundings that Robert W. White was born into and where his musical education began.

Part One: The Rise of Gospel Music and the White Family Singers

While census data post-1940 is not readily available due to the Federal government's "72-Year Rule," a 1958 article published in the Elizabethtown Chronicle by reporter James DeLong discusses a visit to the White family's home in Billmeyer, twenty years removed from that last significant data point. In his writing, DeLong describes the Whites as no longer living in a rented worker's home in Bainbridge, but in a "two-and-a-half story house on the banks overlooking the Susquehanna River," probably closer to Willie White's job in the quarry. Apparently, Willie White was either very good at saving his money or, like Arnett, perhaps he too had risen to a position of some importance in the J.E. Baker Company. By this time, the heyday of the quarry started to fade, and management began to scale back operations leaving only a skeleton crew of workers by the 1950s to keep the quarry's massive water pumps operational and local troublemakers off of company property.

Another unique feature of Willie White and his family's life in Billmeyer was their connection to music, specifically gospel music, which is the main reason for DeLong's visit to the White family household. Sitting diagonally opposed to the White's home, according to DeLong, was the First Baptist Church of Billmeyer. While the church itself no longer exists and its records have since been lost to history, DeLong details how the White family from top to bottom were avid musicians and their first stage was in the choir rehearsals and worship services of Billmeyer's lone African-American church. Like other African-American communities across Lancaster County (and the US), the church was more than just a place of worship for African Americans. It was also seen as the center of community social and political life and, in a community like Billmeyer with families coming from all over to a foreign township along the Susquehanna River, the First Baptist Church may have also been the thread that bound this community together. According to DeLong, all the White children (including Robert) were active in the church and its music program, with younger brother William (or "Willie" Jr.) rising to become its choir director and church pianist by age seventeen. All of the White boys, according to DeLong, played the piano and all the White girls sang. The family even formed a traveling musical group of sorts, known as the White Family Trio, that played in local churches and community halls.

The presumably white reporter, DeLong, may have been at the White family home and writing this account to highlight not just the local success and talents of the White children but also to show how this group was mediating the tensions of the Civil Rights Movement in their area of Lancaster County through music: "During these times when tension grows between [the] races and desegregation has begun," wrote DeLong in a reference to the political climate, "these Christian youths have done [much] to dispel the animosity…that might have existed towards [African-Americans] in the area." As the Harlem Renaissance was coming to an end in the early 1950s, the White Family Trio also fit into a larger historical subset of African-American musical and cultural tradition as black popular music and culture evolved.

According to historian Samuel Floyd in his 1995 book The Power of Black Music: Interpreting Its History from Africa to the United States, the 1950s were the bridge period between the end of one influential era of African-American musical culture to the rise of another. World War II had slowed, but not stopped, the eventual death of Harlem's cultural and intellectual New Negro Movement. By 1952, African Americans were starting to redevelop their cultural radar in new directions, buoyed by a postwar economic boom and a desire to reestablish themselves in American society after serving their country alongside their white counterparts. Floyd highlights two new directions in African-American popular music spawned from the ashes of the Harlem Renaissance. First, the period saw the passing of the baton of cultural and musical achievement from an older generation of African-American cultural figures to a younger version of black innovators and artists. The 1940s and 1950s were not kind to many of the luminaries of the New Negro Movement as the hysteria of the second "Red Scare" ruined many careers and lives of prominent Harlem Renaissance figures deemed communists. Thus, fresh ideas and new leaders were needed.

Secondly, Floyd highlights what he calls the "promise of integration," an idea that in the new culture of postwar America, African Americans would finally get the respect and dignity they deserved after doing their part to help defeat the Axis powers. Unfortunately, this dream was strained as events such as the Brown v. Board of Education decision and the Montgomery Bus Boycott revealed social justice to be a work in progress. Nevertheless, Floyd argues that these two elements resulted in a cultural push to make American-American music and artistic culture more mainstream in the US and thus more acceptable to a larger audience of both whites and blacks. For example, African-American composers Ulysses Kay and George Walker blended mainstream classical music with distinctly African-American elements to develop a new sound for audiences; the development of "cool jazz" with artists like Miles Davis and Charlie Parker to make the art form more accessible to white audiences while still encouraging black experimentation; and the so-called "peak of the great gospel quartets," which made traditional African-American spiritual music the most iconic and accepted it had ever been to the mainstream white American audience.

Gospel music and spiritual hymns performed by traveling African-American musicians had been around since the 1920s, but in the late 1940s and 1950s with its growing commercial base in the booming record industry, many gospel groups became national stars. Acts like the Wings over Jordan Choir, the Mills Brothers, or the Evangelist Singers brought the styles and sensibilities of Southern church music, born in the back country of Alabama or the tidewater of Virginia, to audiences across the country. Since this musical style would have been a cultural way of life to kids like Willie or Ison White, it would not be a stretch of the imagination to see these children participate in and become purveyors of this evolving venue of American music.

The talents of the White children were not just confined to Billmeyer's African-American church. In both the Elizabethtown and Lancaster newspapers of the 1950s, references can be found to the local music group made up of the White children, first known as the "White Family Quartet" or the "White Family Singers" and then later as the "White Vocal Trio," This traveling musical act – almost like a local Von Trapp troupe – played church socials, civic events, and local talent contests and festivals across Lancaster County. For example, an announcement from an August 1954 issue of the Elizabethtown Chronicle touts an upcoming performance of the White Family Singers at a local Evangelical Church of Elizabethtown, Lancaster County. "The musical talents of these young people were discovered by a Conoy township music supervisor," states the author of the article. The writer adds, "Throughout the past several years, under the supervision of their mother, Mrs. Margaret White, the group has been providing musical selections for various religious gatherings." An advertisement in a 1958 issue of Lancaster Intelligencer for the Christian Families Conference at the Neffsville Mennonite Church, Lancaster County, features the White Family Singers as one of the main entertainment draws for the symposium.

Young Robert White, who often accompanied his siblings on these outings as an accompanist on piano or guitar, developed a taste for musical performance while feeding into a popular African-American musical trend, touring about the county with his musical siblings and protective mother as they played these shows. But Robert also had other career ideas – aspirations he would put into motion following his graduation from high school and subsequent military enlistment in 1954. Many of the White children continued their musical journeys in gospel and church music following Robert's departure from the group. Margaret White graduated from high school in 1956, married, and continued to sing locally. Both Floyd and Melvin White continued to sing and play locally before graduating from high school and joining the armed forces. Staying in Billmeyer was not part of the plan for some of these young musicians.

Another interesting tidbit mentioned in DeLongs article is that Willie White is described in the article as a guitarist. In other short contemporary histories of Robert White’s career, the authors state that his first lessons with a guitar were with an uncle, most liked Ison. Could further instruction for Robert White’s early guitar playing have also come from his father? Did Willie White, being probably a self-taught musician, play with the unique thumbnail-picking style that would eventually become Robert’s trademark? While the historical record cannot verify any of these details, White himself seemed to confirm that his first experiences with the guitar and love of music came from his family in an interview with Allan Slutsky in 1985 remembering that, “everyone in my family played something.”

Another interesting tidbit mentioned in DeLong's article is that Willie White is described as a guitarist. In other short contemporary histories of Robert White's career, the authors state that his first lessons with a guitar were with an uncle, most liked Ison. Could further instruction for Robert's early guitar playing have also come from his father? Did Willie White, probably a self-taught musician, play with the unique thumbnail-picking style that would eventually become Robert's trademark? While the historical record cannot verify any of these details, White himself confirmed that his first experiences with the guitar and love of music came from his family in an interview with Allan Slutsky in 1985 remembering that, "everyone in my family played something."

Part Two: The Musical Influence of I. Scott Hamor and the US Air Force

The second musical transition of White's early musical education appeared outside of the First Baptist Church of Billmeyer at the local Bainbridge High School, a small rural school that graduated around a dozen students each year, but had a thriving local music department according to historical sources. The comment of a "Conoy Township music supervisor" in the local press could provide a clue to another local landmark's influence on Robert White's musical development as the White Family Singers often participated in "songs and choruses [shows] at the Bainbridge High School auditorium held each week." The man at the center of Bainbridge High School's musical endeavors was Mr. I. Scott Hamor. According to A Pictorial History of Conoy Township: From Colonial Days to 1976 by local historian Carl Smith, Hamor came from a family that was well known in local lore. His father, Bert L. Hamor, was a local icon, having landed the first plane at the nearby Olmsted Airfield Military Base outside of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (today Harrisburg International Airport) during the closing days of World War I. A graduate of Illinois University and the University of Texas, Bert Hamor parlayed his love of flying from his military service into a career as a stunt pilot for the traveling Rickenbacker Circus, a flight instructor for the US military, and later an air mail carrier for the US Postal Service. His son, known as "Scotty" by his friends, was described in his 1945 senior high school yearbook as "tall and dark" with a love of jazz records and swing orchestra music. Given these interests, it's little surprise that the younger Hamor would go on to attend nearby Lebanon Valley College to study music education. While in college, he got married to his high school sweetheart, Grace Frick of Elizabethtown, graduated with his degree in 1952, and accepted a teaching position as the one and only music teacher/supervisor at Bainbridge High School in his old hometown.

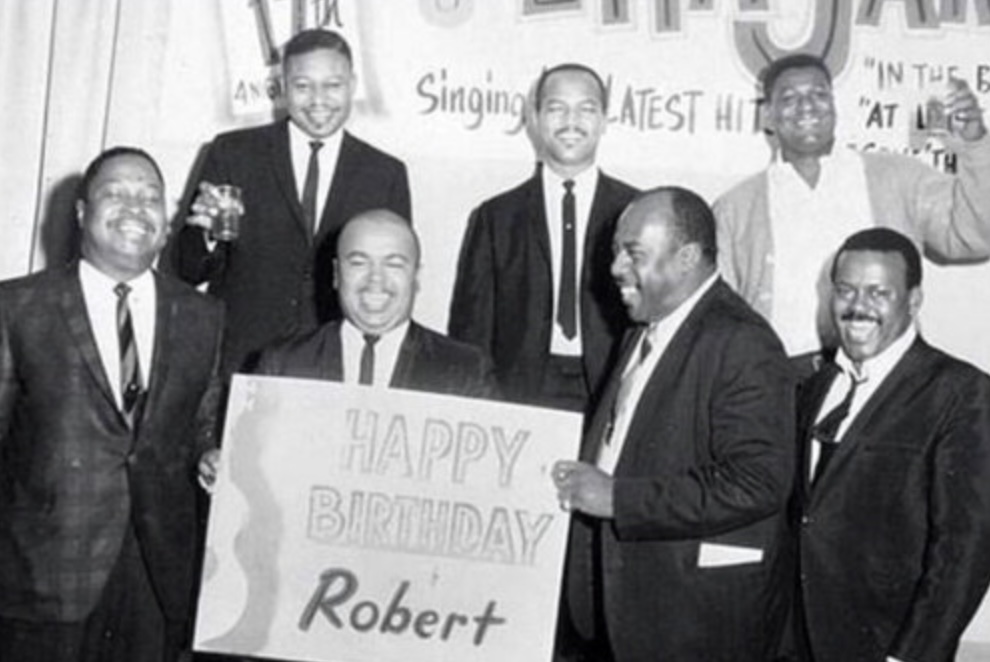

While the exact nature of the connection between Robert White and I. Scott Hamor remains unclear, they must have had some form of student-teacher relationship as Hamor was instrumental in helping to launch the White Family Singers as local newspaper accounts regularly mentioned the teacher at local musical events with his young protegees. A 1954 newspaper account of a concert with the Bainbridge High School Band featured White as one of the central Glee Club musicians under Hamor's direction, a distinction not given to just any student. At his 1954 graduation, White received one of the Senior Awards from Hamor who also chose White as a commencement speaker for the event. Again, both these honors are not positions done for just any pupil at the school. Regular articles promoting music festivals at the Conoy Township High School, such as one from October 1954, feature the White children performing several different types of gospel and religious hymn selected by local music lovers and school officials, specifically under the direct care of Hamor. Perhaps Hamor was almost like a kind of Colonel Parker for the White Family Singers and their budding guitarist sibling. Maybe Hamor's love of jazz and the growing cool jazz/bebop movement of the mid-1950s introduced White to his first taste of the musical stylings outside of his traditional gospel roots. Perhaps this mentorship is where White, again recounted decades later in his interview with Slutsky, developed his love for jazz guitarist Wes Montgomery. One could also speculate that White developed his signature playing style by mimicking Montgomery's tendency of using his thumb rather than a pick, which gave the guitar intro of the Temptation's version of the song "My Girl" that unique Robert White sound. To be sure, his experiences at Bainbridge High must have been positive for the budding musician and given him lasting pride in his now-extinct alma mater. "Graduated from Bainbridge High School," White said proudly, years later when asked where he went to school. Obviously, some of that musical education remained as a possible influence over Robert White's life and career.

Following his graduation from Bainbridge High School in 1954, White enlisted in the US Air Force and became an airborne technician. A brief article in the Lancaster Intelligencer lists White's name among other local youth who had graduated from basic training at Sampson Air Force Base in New York followed by a mention in the Elizabethtown Chronicle of White's graduation from technical school at Keesler Air Force Base near Biloxi, Mississippi, and eventual service overseas with the US Air Force in Japan. White's trip to the Deep South for further military education may have inadvertently had an influence on White's musical education in jazz and early rhythm and blues. Biloxi was a major stop on the so-called "Chitlin' Circuit" of African-American nightclubs where scores of iconic jazz and blues artists would eventually cut their teeth and hone their musical talents. As historian Richard J. Ripani writes in The New Blue Music: Changes in Rhythm & Blues, 1950-1999, popular music was going through a transformation by the mid-1950s. Sliding away was the popularity of pure gospel music and in its place appeared cool jazz, bebop, as well as rhythm and blues. Ripani points out that the stylings of this new music would emerge to be “one of the most important song forms of the decade,” which built the foundation for other forms of popular music. African-American artists like Wynonie Harris and "Big Mama" Thornton influenced others through their rhythmic interpretation and vocal confidence, so future artists like Little Richard and Ray Charles could elevate the new rock and roll. These musical elements of doo-wop, rhythm and blues, jazz, and gospel propelled not just African-American musicians, but also white musicians, like Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis, into the heights of superstardom and would have been on full display for young Robert White if he ventured into the Biloxi musical halls.

White himself described his time in the Air Force as "typical" and that music was a part of this next chapter of his life as well. In one of his interviews with Slutsky, White claimed to have played for the Air Force's elite Top of Blue touring ensemble. Formed in 1953 by Air Force Major Al Reilly, the ensemble was known for its grueling touring schedule, playing 230 shows around the country in 235 days. The Top of Blue could also explain the broadening of White's musical scholarship as it featured group compositions in jazz, classical, instrumental marches, and vocal music. Another interesting music-related aspect of White's military service came during his one-year deployment to Korea as part of the 311th Fighter-Bombing Squadron where he served as a radio communications technician, working on F-86 jet fighters. White had been assigned for overseas service at Osan Air Force Base (code named K55) where he struck up a friendship with fellow air tech Billy Gray from Sheffield, Alabama. In his recollections of this period, posted to an online memorial to another fellow Korean vet, Gray recalled that White was "probably one of my closest friends in Korea" and that White's passion for music (especially cool jazz) rubbed off on him. As Gray described it:

Bob [Robert White] was an extremely talented guitarist who taught me to appreciate and love all forms of jazz music. He formed a jazz trio and played on the base radio station. Often, I would go with him and the trio to the back room of the Enlisted Men’s Service Club where they would practice. Talk about a taste of heaven – this very talented jazz trio, three black musicians, jamming – and their audience of one tall, skinny, white guy sitting there for hours, loving it. Bob seldom went out partying and drinking; he stayed on the base and played his guitar. That was his total pleasure...

White's friendship meant a lot to Gray, so he was disappointed when Robert pulled his colleague aside to remind him about the brutal truth once they moved back to the US:

Bob [Robert White] came to me and said, "You know that when we get back to the States, we cannot run around together." I was shocked. Here I was, a white boy raised in Alabama (but, praise the Lord, not in a home where prejudice was taught) – and I had not even thought about that. But I realized that what he told me was right. In Texas, in the late 1950s, he could not go to the clubs with me; and I could not go to his clubs with him. A thought that makes me sad, even to this day...

While official military records of Robert White's service in the Air Force have been lost, he may have gotten out of the service in either 1957 or 1958. Following his discharge, White entered the next chapter of his life as a professional musician, but one that needed a miracle of sorts to get things going. His term of enlistment ended at Bergstrom Air Force Base, about seven miles from the major urban hub of Austin, Texas.

Part Three: Touring, Studio Work, and the Making of a Motown Legend

After Robert White's discharge, no record survives of any return to Conoy Township, Bainbridge, or Billmeyer even for a visit with his family, and it may be possible that White never returned to Lancaster County or even Pennsylvania before beginning his new career. Now a civilian in Austin, a chance meeting with another up-and-coming musician sealed his fate on the road to Motown. As White described it in an interview with Slutsky:

I was stuck in Austin, Texas…it was there that I met Harvey Fuqua who was looking for a bass player for his band. After hanging out with him for a bit, he came to me and said if I could find him a new bass player for his tour, he would pay $100. I said, "Good news, Harvey…I found him and it's me!"

In the late 1950s, American popular music went through yet another metamorphosis, though this one was decidedly more beneficial to the young Robert White. As pointed out by music historian Samuel Floyd, the advent of the electric guitar and the development of a robust and competitive record and recording industry in postwar America opened the door for young, talented African-American musicians. The guitar became front and center in the composition, and while the guitar player was not always be the band's frontman, the guitar sound and solo became a musical staple.

Harvey Fuqua was another one of the unique and talented African-American artists following this new evolution in African-American popular music. As the leader of an up-and-coming rhythm and blues group known as the Moonglows, Fuqua had performed in several different vocal groups in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, before moving to Cleveland where famed rock and roll disc jockey Alan Freed discovered him and added Fuqua's group to his traveling stable of stars. Record contracts and hit singles soon followed, but caused turmoil within the original band. When White entered the picture for the Moonglows in 1957, Fuqua had recently fired many of the original members of the group and brought in new backing musicians. The new group had already recorded their top twenty hit "Ten Commandments of Love" when White signed on as a bass player. After that, touring became the major focus over studio work and recording.

On the road, Fuqua's new backing band was dubbed the Marquees. This new incarnation displayed their evolving musical style – less doo-wop and saxophone, more solo vocals and electric guitar, as noted by Marv Goldberg, who also explained that one of the vocalists who toured with the group that year was future Motown singer Marvin Gaye, drummer for the Marquees. Gaye, another recently discharged member of the US Air Force like White, had been persuaded to join the tour by a friend and would continue to work and record with Fuqua even after the tour ended. According to White's own account in the Slutsky interview, the tour itself lasted for about a year, crisscrossing the country until the traveling musical caravan ended up in Detroit where Fuqua abruptly quit the group. "The whole thing just petered out," explained White in 1985. He added, "We got the tour extended another week, but that was the end."

Finding himself unemployed and stranded in Detroit, White looked for work as a musician wherever he could. As luck would have it, his next big opportunity came from an unlikely source and catapulted him into the next great chapter of his musical career thanks again to the burgeoning and competitive record industry. According to White's interview with Slutsky, his landlords were the "Gordy females," which introduced him to the family that would eventually build Motown. While White's account here might be correct considering Barry Gordy's father, Barry Gordy Sr., owned buildings in Detroit's African-American community and allowed his children to live in them – according to Barry Gordy's autobiography – the introduction to the family might have also been in part related to White's previous professional relationship with former boss, Harvey Fuqua.

When Fuqua quit the Moonglows, he took a job as a talent scout for local recording company Chess Records. There, he became connected with Anna and Gwen Gordy, Barry's older sisters who also had an eye for musical talent. As Frankie Gaye recounted in his memoir, Fuqua eventually went into business with Anna and Gwen – who became Fuqua's wife in 1961 – and established Anna Records. In The Motown Encyclopedia, Robert Betts explains that Fuqua then brought in former members of his backing band, the Marquees, to do session work, including drummer/singer Marvin Gaye – who married Anna Gordy in 1963 – as well as guitarist Robert White. One memorable session at Anna Records, as related by journalist Don Waller in The Motown Story, White was brought in by his neighbor to provide guitar work. That neighbor was Detroit rhythm and blues singer-songwriter Marv Johnson. Some of the first sessions White played on eventually became the song "Come to Me," which was Johnson's first big pop hit in the US and propelled him to fame as one of the founding voices of Motown.

While White surely would have been noticed in the studio at Anna Records, there also could have been another connection that led White into the orbit of the Gordy clan. In his Slutsky interview, White mentioned that he ran into Gordy and other local record executives playing the local club scene in Detroit. At night, White played local bars with a group fronted by musician Joe Weaver, a local pianist and bandleader. As Kingsley Abbott put it in Calling Out Around the World: A Motown Reader, "In those early times, all these players were selling their talents wherever they could. They would play live most nights in the regular clubs and pick up whatever they could with sessions...I guess they were putting in the range of $10-$20 for sessions then." Gordy liked White's guitar playing so much that he started to bring in White for occasional session work at his new label, Motown Records, before finally taking him on as a regular backing musician. Whether through his rental, session work, connections to Harvey Fuqua, or playing in the local bar scene, as Betts and Bill Dahl explain, White developed a lifeline to the next chapter of his life in the recording industry and the soon-to-be flourishing pop music scene of Motown.

Conclusion

As one of the principal guitarists for the The Funk Brothers house band at Motown, Robert White played on dozens of iconic tracks. His work and playing is especially prominent on Stevie Wonder's 1969 hit "My Cherie Amour," the Four Top's 1965 song "Something About You," and "You Keep Me Hangin' On" by Diana Ross and the Supremes, among other classic Motown recordings. His lasting fame, however, is summed up in a single riff he created in November of 1964 for the iconic Temptations' song, "My Girl." As fellow Funk Brother Jack Ashford wrote in Motown: The View from the Bottom, "His [White's] signature performance on 'My Girl' will stand undisputed as the most famous four bars probably ever recorded." This riff alone seals Robert White's place in pop music immortality.

Through it all, Robert White remained a humble and spiritual man, adored by those who knew him as the "glue" of their sound. "I never felt more loved than when I was with the Funk Brothers," remembered White in the Slutsky interview. While White would not live to see the success of the book and documentary that resurrected The Funk Brother's story, the legacy of the studio band he helped to create is finally being rediscovered and honored by a new generation of music lovers. White's rise to prominence also correlates with the three-phase evolution of African-American music from gospel to rhythm and blues to guitar-driven pop of the modern era that continues to have ramifications for popular music today. Robert White's upbringing in the Billmeyer Baptist Church and the White Family Singers where he learned his musical foundations, his evolution to popular and modern musical tastes at Bainbridge High School and the US Air Force, and his emergence as a professional musician in the early days of record recording and guitar-generated rock all contributed to his unique talent, adapting to the changing waves of the music industry. Perhaps the musical contributions and Lancaster County connections of Robert White may also someday be honored and reexamined in a way more fitting of an unsung Twentieth Century musical icon.

February 2025

From guest contributor Gerald G. Huesken Jr., Penn State Harrisburg |