|

The Voice of America website intoned on September 12, 2011, that “the National September 11 memorial opens to the public Monday in New York City more than a decade after the twin towers of the World Trade Center were taken down by terrorists.”

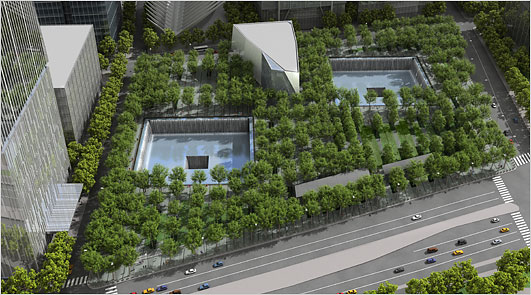

There then ran in simple declarative sentences a description of the dark granite, cube-shaped pools forming “the largest man-made waterfalls in North America.” There were hundreds of trees, the report continued, and bronze panels inscribed with the names of nearly 3000 dead. The five-hour remembrance service heard each name read with the hum of waterfalls in the background, an evocation, perhaps, of Psalm 23, “he leadeth me beside the still waters.”

The Other Shoe

The simplicity of the memorial itself and the prosaic reporting used to describe it was certainly suited to convey peace and reverence, but something else as well. That something is a latent sense of numbness with which the national reaction to the events of September 11, 2011, seems still freighted. In trying to penetrate the anguished inadequacy of the artistic community so far, it is good to remember the insight of Aldous Huxley who asserted that the artists were the “antennae” of a society. The gifted novelist was himself hailing other gifted souls who almost unwittingly channeled the signs of their times into a muted gift of prophecy.

Two offerings by New Yorkers, one a graphic artist and the other a novelist might make valuable stand-ins for the higher culture.

Art Spiegelman, a Pulitzer-Prize winning graphic novelist and cover artist for The New Yorker, lived in view of the Twin Towers. His oversized, two-page scratchy black-ink sketches in his 2002 offering, “Dropping the Other Shoe,” was one of the first artistic responses to 9/11. It was not exactly an encouraging assessment. Three lines resonated for many reviewers in Spiegelman’s lament: “On 9/11 time stopped. By 9/12 clocks began to click again. But everyone knew it was the ticking of a time bomb.” Essayist Deborah Eisenberg’s response in “Twilight of the Superheroes” was equally minimalist. Her book’s cover featured a tearful, battered Batman figure overlooking a terraced apartment in view of the towers. Though the 9/11 literature is still young, it is not throwing up the reassuring patriotic stereotypes that even Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney embodied in such popular films as Casablanca and Captains of the Clouds. Ben Marcus noted in the New York Times that “the dream of the superheroes has turned too dreamlike.”

The Los Angeles Times book review section of September 4, 2011, was sure that the filmed responses were still unsatisfying, at least so far. In that article, book critic David Ulin nominated The 9/11 Commission Report - a government tome - as embodying “a victory of humanity over fear.” This comment, too, reads like minimal reinforcement for such a seminal event.

The Superhero Surfeit

Is it possible for the popular arts to embody what Huxley expected from the more highbrow corners of the culture? Interestingly, the summer of 2011 will go down in the history of American popular film as “the summer of the Superhero.”

From Thor’s strong opening at the El Capitan in Hollywood on May 2 to the eruption of Captain America across the major cineplexes in mid-July, audiences were treated to a popcorn-leavened digitalized revelry in some of America’s most traditional comic-book figures. The summer of 2011 at the movies spanned a gamut from retro-World War Two Captain America to the embryonic X-Men averting the Cuban Missile Crisis down to Ryan Reynold’s Green Lantern given a CGI-laced day-pass from earth to Asgard.

Heroes have been with us since the dawn of time, as Joseph Campbell has made blindingly clear. The movie fascination with heroes from the uncomplicated Tom Mix and Gene Autry down to Davy Crockett and Zorro limns the outline of a well-known trajectory. But to have passed through the anti-hero phase from Bonnie and Clyde to Hawkeye Pierce and then to cram four styles of avenging sacrificial superheroes into one summer may indicate the presence of a phenomenon. What critic Adam Mason called “the crumbling superhero genre” may have been a premature analysis given that another Batman sequence is already in the works almost before Christian Bale can get his cape on.

Is there something metaphysical at work here? Could the dream stream that issues forth (however inadvertently) from the creative minds of screenwriters and producers into popular film be signaling something more significant? Is this asking far too much of the popular arts? European-born film critic Seigfried Kracauer did not think so. A generation back he gave testimony to film’s subdued psychological dispositions: “those deep layers of collective mentality which extend more or less below the dimensions of consciousness.”

O’Connor and Jackson’s “Foreword” was written by a public intellectual very much in the mainstream, the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. In trying to penetrate what he called “the only art where the United States has made a real difference,” Schlesinger himself made so bold as to take film seriously as a cultural signpost. As a popular art, he wrote, film “is the carrier of deep if enigmatic truths.” The movies “offer the social and intellectual historian significant clues to the tastes, apprehensions, myths, inner vibrations of the age.” Schlesinger’s much neglected commentary probed film’s “latent content” as well as its manifest content. The movies, he said, ”tell us not just about the surfaces but about the mysteries of American life.”

Dreams and Nightmares

The resemblance between watching movies and the dream state is not a new proposition. It’s dark. You’re in a fairly strange place. Normal human interaction is suspended. The colorized performers are blown up to the size of a warehouse wall. In The Soul of Screenwriting, Keith Cunningham considers film as close as most people get to an “out of the body experience” - boundaries are down, inhibitions are dulled or enhanced by the effect of pulsating or sympathetic music and the subconscious is more free to frolic. In deciphering the dramatic content of movies, he draws upon the dynamics of tension and release which he sees as its essence, usually expressed as “growth through crisis.” Thus, in that summer of 2011, the would-be Green Lantern candidate, Hal Jordan, has issues tracing back to his father and his own failure to break through the barriers of his own self-imposed limitations. Captain America must break out of the barriers imposed upon him by meddling “suits” if he is ever to achieve his full measure.

It is well-known that the hero as construct has been in trouble in American culture for some time. What remains intriguing is the appearance of so many crisis-bearers/problem-solvers in one summer - actually a nine-week period. What “inner vibrations of the culture” were the popular arts showing forth? What did they tell us about “our common dream life,” as Schlesinger phrases it. This is a murkier realm that most film critics are perhaps wise to steer away from, but social historians, as Schlesinger indicated, are willing to broach it. At least suggestively.

The opposite of the dream state (but closely allied to it) is, of course, the nightmare. In The Terror Dream, social critic Susan Faludi sketched the terrain of a post 9/11 America that had its illusions of security and invincibility shattered. The “protective myth,” she wrote, came crashing down along with “the idea that our might makes our homeland impregnable, that our families are safe in the bower of their communities and our women and children safe in the arms of their men.” The heaviest disillusionment ripped into the would-be safeguards of our security, she argues: “The events of that morning told us that we could not depend on our protectors: that the White House had not acted on warnings of impending attack, that the FAA had not made safe our airports and planes, that the military had not secured our skies, that the 9/11 dispatchers had not issued the necessary warnings…”

Those disturbing emotions, Faludi went on, “inundated our cultural dream life, belying the bluster of the ‘United We Stand’ logos.” The narrative we had trusted in from the days of John Wayne no loner held. In movie terms, audiences now know that the President is not Captain America. Thor-like demigods and Green Lantern cosmic guardians - where are you?

Heroic Minimalism

As if echoing Faludi, Ryan Reynolds’s Green Lantern barely pulled off his conquest of self-doubt in the closing scenes. (“Will someone slap him?” one reviewer asked). The Avengers needed to sharpen their skills in a much less ambiguous time period - the deep freeze years of the Cold War. This was heroic minimalism amidst a plethora of superheroes. For the Avengers, victory came in October 1963 not September 12, 2001.

In the words of Bonnie Tyler’s 1980s offering, we need a hero. The media saturation on September 11, 2011 - the tenth anniversary of the fall of the Twin Towers - insisted that there were heroes aplenty among the first responders and ordinary civilians that grim day in 2001. While there is good evidence for this claim, in the larger analysis the political culture failed to respond successfully. The United States went into a full-fledged invasion of Iraq which thoughtful commentary has conceded was a failure. “The Iraq war was intended to project American strength in the world,” wrote Ambassador Peter W. Galbraith in Unintended Consequences, “instead it revealed weakness."

And then came more numbing pathos in the late summer of 2011 with the downing of some of the same Navy Seals who actually killed Osama bin Laden, the author of the decade of discontent. Once again the dropping of yet another shoe (killing bin Laden) was followed by a deadened, almost speechless anticlimax. Even the recent drone strike in Yemen killing Anwar al-Awlaki has been met with calls from the ACLU and others that he should not have been assassinated by the CIA, but should have been captured and tried, allowed the rule of law.

“We need a hero.” Was the superhero surfeit of Summer 2011, then, projecting a society unconsciously aware of Faludi’s thoughts on vulnerability? Will there never be the kind of resolution as occurred (at least ostensibly) in the Cuban Missile Crisis and in Captain America’s topos of World War Two? The summer of 2011 at the movies offered an often ambiguous response: heroic minimalism in a season of superheroes. Thor fell from heaven - his on-earth sequences enlivened the film more than heavenly Asgard’s computer-generated props, and the Green Lantern barely pulled it out in the end. The most clearcut victories in the summer blockbusters traced back to other eras of national peril. Faludi thinks the nation’s “myth of invincibility” was irretrievably shattered on the morning of September 11, 2011. She may be right. Both high and popular culture seem unable to come to terms with the jolt to consciousness that the events of that day inflicted.

Finally, the piece de resistance: Time magazine’s September 19, 2011, special tribute edition “Beyond 9/11” shocks with its severe black-and-white shots of everyone from President George W. Bush to armless Iraqi civilian Ali Abbas. The images - even of Rudy Giuliani - are funereal not heroic. The 9/11 Memorial at ground zero with its dark granite, cube-shaped pools rests recessed, somber, quiet, unlike the heroic, jutting presence of the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Memorial, or even the recently unveiled Martin Luther King Memorial.

Is the anniversary of 9/11 the reason for the superhero summer - yet also the reason for the almost subliminal, proleptic undercutting of it as well? Audiences trying to cocoon themselves in the reassurances of another era could not quite escape what blogger Tim Grierson claimed - that something seems gone for good. Or at least that the numbed mood in the special National Cathedral Day of Prayer on September 14, 2011, replayed over Trinity Broadcasting, has yet to subside.

October 2011

From guest contributor Neil Earle

|