The historiography of men’s magazines is quite large. Scholars have studied specific titles or genres, ranging from Esquire to Playboy to pulps. Others have analyzed the impact of men’s magazines upon various facets of American culture. However, forgotten today is one periodical that dominated the genre throughout the 1950s and 1960s: True – the Man’s Magazine. Starting out as low-brow, albeit purportedly factual, confessionals in the Depression, True revamped its format during World War II, stealing Esquire’s chief illustrator Alberto Vargas, defied paper shortages, and became the first man’s magazine to reach a circulation of over one million copies per month. With the exception of historian Thomas Pendergast, who has documented True’s format change from 1944-1950 to become the Esquire equivalent for the “hunting, beer, and poker set,” True has all but been ignored. This essay attempts to uncover what made this magazine the periodical preference for men in the atomic age. In particular, this essay focuses on True’s self-described “best” issue as the 1950s ended: the twenty-fifth anniversary commemorative cover-dated February 1961.

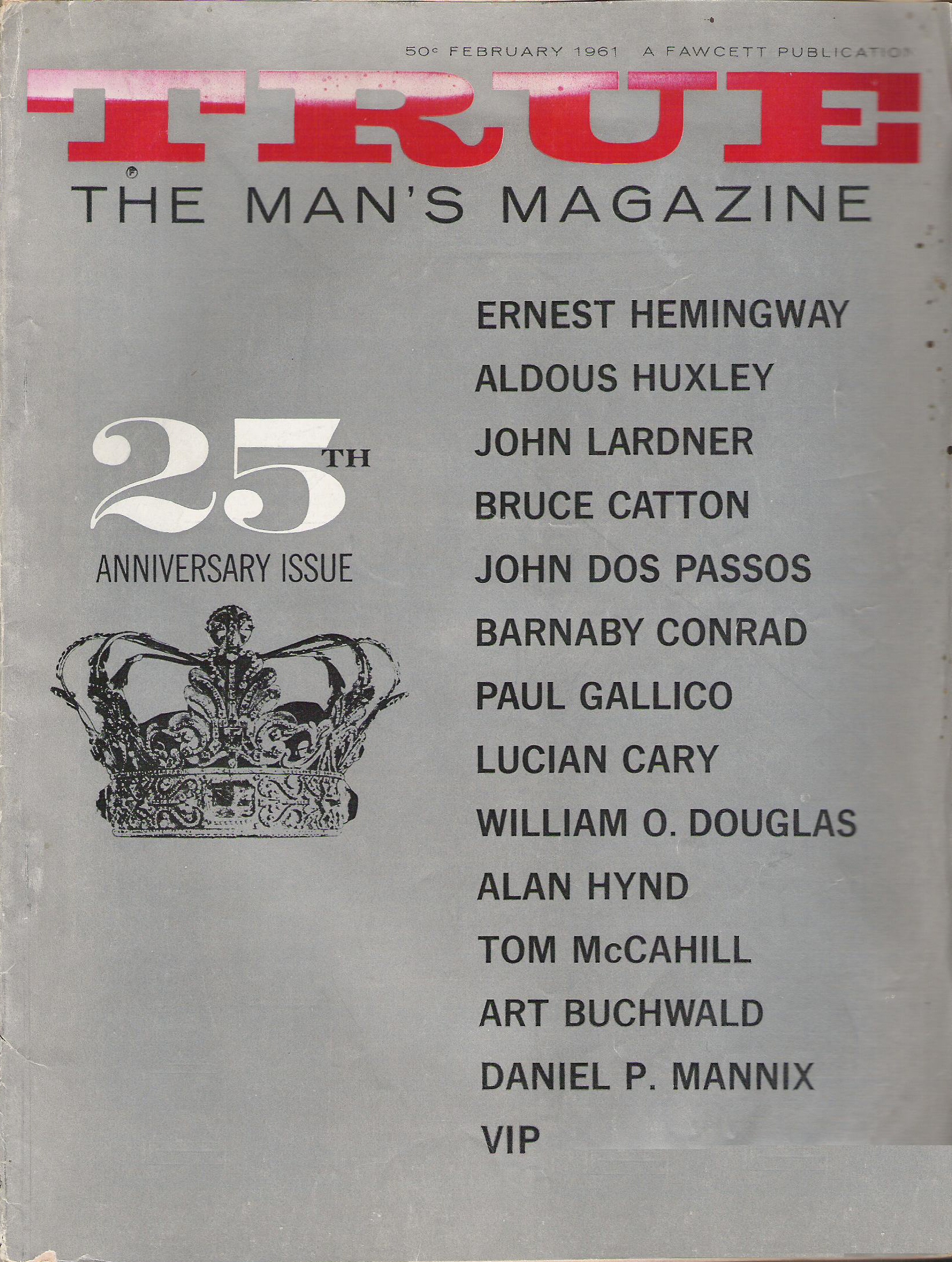

True honored its anniversary with a series of books containing “best of” selections of articles and cartoons. However, for the magazine itself, editor Doug Kennedy previewed the celebration to come in the January 1961 issue and included the cover and broke down the 182-page issue by author (and one artist) ranging from True’s editors to Ernest Hemingway and Aldous Huxley. “The above list of famous writers,” Kennedy notes, “will clue you in to the scope of our super-colossal 25th Anniversary Issue” so you will know “what to expect when you rush off to your newsdealer and mailman to pick up next month’s ‘Collector’s Item’ copy.” This list of names underscored True’s appeal: the utilization of common male characteristics that united all men, regardless of social standing. Such qualities were frequently found in history, as many articles expressed nostalgia. However, writers did not just simply yearn for bygone eras. According to Thomas Pendergast, True asserted that everything it published was based entirely on fact instead of fiction, a “pet belief” of editor Horace Brown, who masterminded the revised format. As a result, readers only encountered “true” men, and in the anniversary issue, the magazine emphasized that the successful hero was one who maintained the masculine core of yesteryear, but used those values to transcend the past and actively create a new tomorrow.

Upon opening the anticipated issue, Kennedy greets readers from the publisher’s point of view: “First, we’re proud, editorially, because the staff of True thinks this is the best issue we’ve ever produced. It’s certainly the biggest. The issue has set other records, too: biggest print order in our history, commensurate with out new circulation guarantee of 2,400,000 (another record), equally important, the advertising department has come through with more advertising than has ever before been published in this gazette for gents.”

The issue’s articles were a mix of different genres and were in no particular order. On the intellectual front, Aldous Huxley predicts the world for True's projected fiftieth anniversary in 1986: "by the end of the present century there will be six billions. It is against the background of this unprecedented biological fact that the dramas of man’s political, economic, and social life are destined to be played.” Moving beyond atomic war, Communist China, and other factors that could heat the Cold War, the brave new world Huxley describes is one of automation, “leaving humans beings free to use their minds and hands in craftsmanship, in mechanical tinkering and invention, in the practice of an art either as means of communication or, where there is no special talent, as a form of occupational therapy.” However, “leisure has its problems. Sex, drinking, looking at TV, watching other people play games and even playing games oneself are not enough. Something more purposeful and constructive is required to make leisure tolerable.” Huxley has no answers, but concludes that “If 1986 is to be a good year, we must work hard and fast, beginning right now in 1961.”

Huxley poses the predicament, and other authors responded, each composition contributing a call to all men-of-action that covers the entire social spectrum. In the political sphere, Senator William Proxmire declares “Democracy is Dying in the U.S. Congress.” With this alarming title, Proxmire explains the emasculation of the Congressional body: “Never in our history has a vital, active Congress been more important – yet my colleagues and I are held helpless in the grips of a powerful minority. We must smash the old traditions that stifle progress – and we must do it now!” Proxmire further outlines the problems confronting lethargic lawmakers, from a “bureaucratic committee system” to “a Senate tradition of indefinite debate fully supported by sacrosanct rules, the necessity of legislation passing both Houses in identical form, the Presidential veto.” The senator offers suggestions to streamline the Ship of State to make the political process more action-oriented, which he claims would maintain the original system set up by our Founding Fathers.

Far from Washington but no less passive, U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglass chose not to embellish the hi-jinks in the High Court. Instead, Douglass reminisces about his time hunting with the Ghashghais – a group of Arabian horsemen. The justice’s excitement enhanced his prose, such as his description of hunting partner Malek Mansour, who had spotted a hawk. Douglass admired his partner’s stallion which never lost the hawk, and “was still on a hard, fast run when Malek Mansour dropped his reins, stood slightly in his stirrups, and brought the hawk down with one shot.” The camaraderie between horse and hunter rubbed off on Douglas himself: though an outsider to the group, the justice was surprised when a young colt entered his tent and “nuzzled me looking for sugar. He kept coming back as a dog might, friendly and intimate, a regular member of the family.”

Likewise, following Douglass’s Arabian knights, author Daniel P. Mannix contributed his own article about hunting. Mannix concentrates on austringing, or “training the short-winged, forest hawks to hunt for you without losing an eye in the process.” In particular, Mannix details his experience with Tara, a goshawk with a four-foot wing span and “such a grip that it could drive the talons through the skull of a rabbit with one conclusive clench of its fists, causing death almost instantaneously.” Despite the intimacy between hawk and hunter, Mannix concludes that raising a goshawk is a full-time job, one that he didn’t have time for. Thus, he freed Tara in the wilds of Wyoming and expressed confidence that she could easily find a mate.

In another article about hunting, Peter Barrett highlights his safari in Hawaii, accompanied by Governor William F. Quinn, who was big-game hunting in his home state. Barrett applauds the statesman for downing a ram that sported “a generous curl and a half” in its horn and for bagging “seven-boars-with-seven-shots”; one photo showed the governor and his hunting party roasting a boar in a feast-filled luau. Emphasizing that this was the governor’s first big game hunt, True posits that anyone could score such impressive trophies, and provides a color map with symbols showing the animals available in the “game-filled state.” In maintaining its fact-based standards, the article ends informing readers that they could contact True “for help in planning a big-game hunt in the Hawaiian Islands – even if it’s just a side trip out of Honolulu – and for airline travel information” followed by an address. Along similar lines, the “Pamplona!” photo essay highlights a “Spanish Folk Festival” complete with running bulls. Photographs by Henry Cantor-Bresson and captions from Ernest Hemingway depict business-suited gents and local-attired folk fleeing the bulls together.

Just as hunting had done with Justice Douglass, Governor Quinn, and Mannix, True also used boating that united men under one banner. In the issue’s longest feature, Tom McCahill devotes nearly forty consecutive pages to his love of all things seaworthy. McCahill traces boats from Noah's time to now, and notes the sport’s transformation from being a prior generation's luxury into one "being enjoyed by everyone from beatniks to bank presidents." Indeed, McCahill bestows a title upon his sport with a claim that "boating in general has blossomed, bloomed, and burst into America's Number One Recreational Sport."

With this disclaimer, McCahill centers the rest of his article to reviewing different models of boats trying to find harbor in the pockets of men. Lavish photographs accompany the text, and the layout is cosmopolitan in nature; an $85,000 Rybovich sports-fisherman vehicle sails alongside a foldable one-seat aluminum pram; either one “makes a skipper of its owner, opens the doors to places that the landlubber never knows." McCahill's reviews run the gamut of thirty-six foot houseboats to 8’x10’ pontoon craft, providing men with any sort of means of escape.

McCahill's article's length is due to the numerous ads that surround his text. Manufacturers directed their goods to find harbor in the pockets of various men. Glasspar promised that their boats provided a "maritime mardi gras" with a color photo that showed just that. Meanwhile, Brunswick Boats designed a "Million-Bubble Ride" that that was "America's #1 Deal Boat for Family Fun." For those who wanted a swift ship-of-the-line on sale, the Chris Craft Cavalier claimed that their goods were "So Big and Luxurious, so sleek and fast, so low-priced!" Solicitations flooded the forty pages, from fishing tackle to boat trailers, indoor to outdoor engines, direction finders to depth sounders. For readers daunted by such selection, McCahill was there with such helpful hints as the following: "Some engines are better adapted for racing, endurance runs and other hardship trials, while others feature ease of operation, trolling speeds, and, in some cases, economy. There's a rig being built in America today for just about any possible maritime use needed." Indeed, the conclusion suggests that this escalating trend in boating is, if anything, patriotic. According to the author, our nation's history read like a melting-pot manifestation of maritime destiny: "In summing up, it's only natural that Americans should take to boating as they have; after all, it's in their blood. The largest majority of our citizens are here only because some ancestor had the guts enough to take a sporty trip across the ocean long before the days of radio, modern navigation equipment, electricity, and even power plants. These cats were real boating enthusiasts - so don't look aghast when Junior says, 'Pop, let's get a boat.' When you do get it, you're only doing what comes naturally." In case some man out there still weren't convinced, True also offered True - Boating Magazine, a "fact-crammed" quarterly that included information on "how you can build an outdoor racing catamaran."

Exotic locals and adventures abroad whisked readers away into a consumer kaleidoscope in ads and travelogues. A typical example was the Panoramic Colorslide Projector that encouraged cosmopolitan readers to “visit France, Japan, U.S.S.R., Italy, Mexico, etc., in Living Color and Sound.” Automobile ads also emphasized the ability to escape the confines of an automation lifestyle. One layout from Pontiac asserted that a team of teenage test-drivers legitimized the hardiness of their vehicles. The accompanying image showcased the youngsters who drove the car “101,002 tough miles!” Writer Barnaby Conrad describes the hardiness of another kind in his travelogue of Tahiti, where he claims that “there is a French ordinance that says all women must wear bras but I guess [the house servant] can’t read French because all she had one was the lower half of her green and yellow floral pareu.” One color photograph of a bared and shapely Tahitian torso assisted his assertion.

On the other hand, for the more economically minded traveler, Paul Gallico writes “My Bargain Expatriate World” where he “can escape the costs and cares of the twentieth century wherever I choose.” Having chosen Europe, Gallico states that cash-strapped sojourner can “rent castles for $6 a day,” see “native-bodies – Bikini-clad” everywhere for free, and even make a profit in the Riviera, which offered “unlimited treasures to the scuba diver” with photographs that illustrate his points. Gallico assures readers he is not a tax dodger, but could still rent “a property high up on an Alp which included two furnished houses with garages, a swimming pool and a staggering view – all for $75 a month. Four hundred dollars a month saw me entire living costs, food, servants, car, etc. paid. One can easily pay that much for an apartment in New York.” Like Barrett’s essay, Gallico’s article ends with a claim that even skeptical readers could experience this bargain: “For complete information on seeing Europe this year, write to Travel editor, True Magazine” followed by an address. Likewise, the “All Roads Lead to Rome” feature displayed the latest trends from the center of the classical world, with prices from a five dollar ostrich belt to a $100 wool-lined cotton car coat. More illustrations asserted that clothes do make the true man.

Barnaby’s and Gallico’s smile-clad women were a glimpse of the genre’s slant on the fairer sex. In 1945, Pendergast notes, Horace Brown had asserted that masculine men had to “try their damndest [sic] to figure out what women are all about.” Fifteen years later, Kennedy’s selections were still exploring the relationships between men and women, husbands and wives, and the gender roles of all. One such article was Art Buchwald’s “Why the Frenchman has it Made,” in which Buchwald examines the low divorce rate in France.

In his attempt to uncover the secrets of happy matrimony, Buchwald suggests that such firm wedlock was due to French values of love and morality. Like the other authors, Buchwald applies his factual findings for readers, suggesting that if Americans studied Gallic gallantry, “they could cut down their own divorce rates and, with the billions of dollars saved in alimony, be the first ones to get to the moon.” Buchwald traces happy marriages to open deception by both parties, claiming that the both husbands and wives could have amorous admirers “as long as it doesn’t interfere with the family’s two-hour lunch period or the evening dinner.” Furthermore, France’s patriarchal society leaves a divorced woman in detrimental standing among her peers, and “no woman has the right to inspect her husband’s conduct or spy on him in any way, as her husband in all cases is superior.” On the other hand, a husband would certainly stay with his wife, especially if she were experienced in concocting fine cuisine. Cartoons enhanced Buchwald’s argument that, properly equipped with a cook and concubines, Frenchmen certainly had it made.

In the second article highlighting the role of women, Edmund G. Love describes his own experiences as a soldier in the Second World War. In “For Every Guy – GIRLS!” Love displays the trapping of a female mind that wants to snare a man. Love centers on Flo Lansing, who “was not only a WAC officer, she was a beautiful and intelligent girl” and understood the “law of supply and demand – a boy for every girl – and she undertook to supply her fellow WACs and a few of the civilian woman employes [sic] with the necessities of life.” Stationed in San Francisco, Lansing used her rank to delay troop movement passing through to the Pacific. Lansing managed to tie up paperwork and medical exams; indeed, Love himself had an extended fifty-four day stay while on route to Hawaii. During that time, Love spent his time seeing two man-hungry WACs. Unfortunately, Love unknowingly exposed the WACs and shortly thereafter, Lansing shipped the men overseas. “I never heard of Flo Lansing again,” Love writes, “and I never knew whether she changed her ways, but I strongly suspect that she did not. In December, 1944, we got a second lieutenant from the States who claimed he had spent seven months in San Francisco waiting for a ship. The commanding officer didn’t believe him, but I did.”

Amorous behavior was one aspect in the armed services. However, men had more to do than engage in the battle of the sexes while performing their duty. Like many men's magazines, True frequently ran stories about World War II. In 1961, True still published factual articles about that conflict, but for the anniversary issue, writers concentrated on other wars. For instance, Pulitzer Prize winner Bruce Cotton spotlighted the coming of the ironclad ships in the Civil War. For the military buffs in True's audience, Cotton dives into the evolution of naval warfare and includes color paintings illustrating the naval battles between the Blue and the Gray.

For those interested in more warfare, John Dos Passos writes "The Undefeated Dignity of General Bill Dean." Passos reconstructs how the "Korean Reds" captured Major General William Dean and "froze him, tortured him, tried to brainwash him. But the general took all they had - and spit in their eyes." However, despite the bravery of Dean's men, Passos glorifies more than the macho mannerism of the Major General. Passos consistently points out that Dean himself felt he deserved no such hero's welcome. Even as the top brass presented Dean with the Congressional Medal of Honor upon returning home, Passos notes that Dean "kept reminding the reporters that he was a general captured because he took a wrong turn." Dean survived the horrific conditions and treatment in enemy territory, but it was the general's genuine humility and his recognition of his limits that made him a True man.

Indeed, Passos describes Dean's hardships in his early years: the general had initially failed West Point and was too young to enlist in World War I without his mother's permission. Concerning his assignment in South Korea, Passos records Dean's objective to "teach the Koreans how to run their sawed-off nation American style [yet] he regretted he hadn't tried to learn more about the Koreans before he tried to do that job." Passos also notes Dean's own private feelings in his capture; the general was proud "of how few of his men surrendered in the European Theater [of World War II. Now,] he felt ashamed enough squatting in that little cage, a prisoner." However, having learned first hand both the kindness and cruelties of his captors, Dean himself summed up his experience and revealed those hard lessons: "The most important discovery to me was that the ordinary Communists who guarded me and lived with me really believed that they were following a route that could lead to a better life for themselves and their children....It was easy for us to say they were mistaken but not so easy to explain to their men of limited experience just why their ideology must fail...we can't convince them with fine words, we've got to show them something better. We must have an answer simple enough for the dullest of them to understand.” Passos concludes, "The American people were right to make a hero of him." Indeed, Dean himself modestly responds to Passos’ words in a letter, thanking Passos but suspecting “that the author has weighed the events of Korea heavily in my favor – a kindness, which if not entirely deserved, is sincerely appreciated.”

Man's imperfection and the ability to recognize and overcome such limitations was staple of the heroes of True. That certainly seemed the case in John Lardner's article titled "The Life and Loves of Magnificent Mick" which features the roller-coaster life of professional boxer Mickey Walker. Lardner's biography depicts Walker as the lightweight champ who "married seven times [to a total of four women] and drank enough to keep six bootleggers busy” during Prohibition. At first glance, Walker seemed like the one-dimensional boxer who just didn’t know when to quit. Walker's toughness invited readers to admire, if not applaud, him as he fought heavyweight champions and refused to back down.

In one example, Lardner describes Walker's match with World Heavyweight Champion Max Schmelling in 1932. Lardner writes that Schmelling punched Walker “almost senseless in the eighth round. Glassy-eyed and slack-kneed, Mickey went reeling from one side of the ring to the other." Finally, Schmelling himself broke down and asked Walker's manager, Doc Kearns, to "stop it!" Kearns “dragged his battered business partner off to the showers. ‘I guess this was one we couldn't win, Mike,’ the Doctor said somberly, when the fighter pulled his brains together. Walker gave him a blurry but arrogant stare. ‘Speak for yourself, Kearns,’ he mumbled, spitting blood on the floor, ‘you threw in the sponge, not me.’" Walker lost the match, but his mop-up muttering gave the diminutive underdog a testosterone triumph.

Nevertheless, despite Walker’s role as the professional tough-guy, Lardner portrays him transcending the image of the stereotyped boxer. In 1935, one year after the Volstead Act fizzled out, Walker found himself penniless in a bar. After a fellow tavern traveler called Walker a "cheap bum,” the boxer’s temper flared up to take his insulter down. "Then, all at once, the interest died. The liquor and the nonsense turned cold in his stomach." Instead, Walker asked for a cheap beer and, contrary to True’s many liquor ads, "drank it off, and then, on the spot, he quit for life." Beginning a new phase in life, Walker turned to art. Lardner writes, "Walker of 1961 is a man who, without having taken a lesson in his life, can get his pictures shown in one-man shows, and can even, once in a while, sell one." The adjacent photograph shows the artist flanked by his works, proudly showing off his paintings rather than his punches.

Lardner includes a dialogue between Walker and his old-time fighting friends from a 1955 show:

"'He called you a primitive," said Benjamin to the painter.

"Yeah," said Walker smugly.

"Twenty years ago, if somebody called you that, you'd a knocked him on his can," Benjamin said.

"Yeah," said Walker, "I would. But all this guy means is that I got something special. He can't figure out what it is, but it's special."

"Maybe it's that thing on your head," said Anthony Galento, another retired tiger, referring to Walker's beret.

Lardner interjects, "It's true that this top-piece gives the Mick an indescribable air of Jersey-Parisian je ne sais quoi and fills his friends with disgust." Nevertheless, as indicated by his haute contour, Walker manages to cross class lines.

Similarly, True’s Gun Editor, Lucian Cary, composes a piece about Sam Colt, a showman who had invented nothing, but by age forty-two, built “the largest private firearms factory in the world and he owned about nine-tenths of it.” Colt tapped into the essentials of universal manhood: one lavish illustration depicted the showman presenting the Czar of Russia a Colt heavily inlaid with gold.

However, not every protagonist had such happy endings. Writer Alan Hynd’s "The American Tragedy Murder," describes the life and death of Chester Gillette, a playboy who whacked off working girl Grace Brown with a tennis racket in a row boat in order to marry an upper-class beauty and avoid a scandal. (True placed this story right after McCahill’s boating article; among the prose is one cartoon depicting a husband constructing his wife's future casket and an ad for more boating gear).

However, Gillette received no sympathy from either his peers or the author. Hynd writes that Gillette had “the best lawyer money could buy – a former state senator named A.M. Mills, who was an organ-toned orator given to pulling out all the stops the courtroom,” but it came to naught. Instead, as the trial wound down, “the 12 good men and true – four farmers and a blacksmith among them – were out just five hours to assay what they had been looking at for a month. Then they returned with Chester Gillette’s death notice.” Gillette’s electric chair execution sparked more than the demise of a murderer. True inserted an editorial that “with this drama of greed and lust and death to draw on, Theodore Dreiser wrote An American Tragedy, a novel which has become a classic in American literature. In it Dreiser was attempting to show broadly what evil could come from the wholly material goals the rising generation had set for itself: wealth and position. He could hardly have picked a better example for the moral he had in mind.” With the implication that Gillette was snared by affluent aspirations and had lost his touch with the common man, Hynd could hardly have picked out a more appropriate jury to bring about justice.

Similarly, in a condensed, yet “double-length feature” novel, Gene Caesar’s “Tom Horn: Rifle for Rent” also detailed the fate of a man whose social environment grew beyond him. Just as Gillette lost touch with the realities of the working world, Horn, a vigilante detective, could not transcend the trappings of a disappearing past. “He rode alone and died alone, a professional killer. Still, thousands mourned his passing, and the end of an era” the tagline announced, next to a colored rendition of the rear view of a hanged man.

The author contrasts this lone gunslinger with other “old-time gunfighters” whose masculinities were in doubt. Unlike the “small men, quick and nervous intent, soft-hands and white-skinned and pudgy-faced, men with that same curiously-effeminate quality in their movements that bullfighters and male ballet dancers have today,” Horn was “six-foot one and carried and amazingly wide set of shoulders.” With sun-bronzed skin and calloused palms, Horn “looked for all the world like a top cowhand or even a champion rodeo-rider – both of which, as a matter of fact, he was.” Among images of mustached cowboys on the range, Caesar quotes an anonymous “grizzled old-time cattleman,” even mimicking the western drawl: “Sure he killed a lot o’ men – Apaches, outlaws, cow-thieves – and he only started killin’ cow thieves after it got so juries wouldn’t convict ‘em. Even then he always gave ‘em notice, give ‘em a chance to clear out fust. He rode though a lot o’ nester country and he rode alone. Any o’ them he wanted to try that fust shot, they had their chance.”

However, despite his success, Horn is framed for the murder of a teenage boy. Caesar quotes the townspeople wondering, “Maybe he killed the boy and maybe he didn’t. What difference does it make? The man admits he’s a killer, even brags about it. This is the year 1902! You can’t have men like Horn running around loose anymore." Indeed, the trial confirmed the fears of a new century, with Horn as a reminder of an era out of date. Caesar writes that the prosecutor mocked the notion that Horn, as an old-time detective, could just halt horse-thieves merely with his reputation. Despite leaky evidence, the prosecution claimed that if let go, “he’d be back out on the range killing off whole families in a few weeks.” That prophecy prompted psychological pandemonium when Horn escaped, albeit for both folk and felon alike. Caesar writes that, after eighteen months in jail, Horn saw modern day Cheyenne with sober eyes, “at automobiles parked on the streets, at a carnival with a steam calliope, at the decorations for Frontier Day when dudes would swarm in for a comic-opera celebration of a West they’d never known complete with tamed reservation Indians. For the very first time, Tom Horn realized what the men who’d condemned him to die had always known – that this was the Twentieth Century, the year 1903.”

Horn is recaptured and later hanged. Caesar provides an epithet for the deceased, suggesting that though Horn was innocent, he was symbolically “a casualty of a changing world. The West couldn’t possibly have been tamed without men like Tom Horn but in a tamed West there was no more need, no more room for such men.” Indeed, Caesar ends with the old-time ranchers who claim that Horn lives on in seclusion, haunted by the ghosts of the past.

The anniversary issue ends with several pages of advertisements under the heading “True Goes Shopping.” While the features depict a yearning to get away – either into a stylized past or an escape into elsewhere – the magazine encouraged their readers to indulge in a fantasy of factory goods. As Kennedy’s introduction stated, the advertising department compiled the greatest number of advertisements for their celebration. True provided more fishing gear, postage stamps, Honky Tonk Piano Records, zebra skins, telescopes, hypnosis kits, energy pills, U.S. Army parachutes, Civil War replica belt buckles, French cradle telephones, and a one-page solicitation for The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Sex, complete with testimonials from a doctor, teacher, judge, and minister. Ending the issue is “This Funny Life,” an illustrated feature presenting reader-submitted anecdotes that are, like the “Man to Man Answers,” the readers’ opportunity to participate in the periodical’s mission of fact-based masculinity. The stories, whether about handling weapons of war, defusing the old battle ax at home, or questions ranging from Jack Dempsey’s restaurant to the origin of the proverb “the goose hangs high,” confirmed that True permeated all walks of life.

Appropriately, Major General William Dean’s letter has the last word, and after congratulating True on its anniversary, he adds, “During the past quarter-century you have provided a source of stimulating reading enjoyment to people around the world.” That number only increased: in 1967 and 1968, the spines of each copy of True magazine gave circulation figures of 2,450,000. True was definitely the man’s magazine.

July 2008

From guest contributor Peter Lee |