|

The time was 1964. The ‘60s revolution hadn’t

quite hit, but the rumblings were audible – racial riots

burned cities, the expanding war in Vietnam crept into headlines,

and Beatlemania swept through the U.S. The nation was still

reeling from the shock of a presidential assassination, and

the cold war was in full force. Some people longed for simpler

times. Nostalgic programs like Bonanza, Gomer

Pyle, and The Andy Griffith Show dominated TV

ratings, and Mary Poppins set box office records,

even as darker movies like Dr. Strangelove gained

audiences. Amid all this change, Americans had another place

to retreat – the venerable institution of baseball,

a symbol of constancy through the madness.

The place was Philadelphia. A Horatio Alger story in reverse,

the city had started at the top and steadily worked its way

down. It was once the second largest English-speaking city

in the world, birthplace of democracy and the federal capital,

but Philadelphia gradually lost influence in national affairs.

By mid-century, it was a gritty working class metropolis with

ethnic tensions and decaying neighborhoods. While many Americans

looked to their local baseball teams for pride, unity and

escape, Philadelphians were trained to look the other way.

And for good reason: Between 1919 and 1947, the Phillies finished

in last place seventeen times, and next-to-last seven more.

In ten separate seasons, the Phillies lost more than twice

as many games as they won. After a brief reprieve, the team

settled back into the cellar in 1958, beginning a stay of

four grisly seasons. In the last of these, the team set an

all-time record of 23 consecutive defeats, a mark that still

stands.

Fortunately, Philadelphia had two major league teams for much

of that time.

Unfortunately, the other one, the Athletics, was nearly as

bad. Imagine how Philadelphia felt when both of its professional

baseball teams finished at the bottom of their respective

leagues’ standings in 1919, 1920, 1921, 1936, 1938,

1941, 1942, and 1945. The Athletics quietly packed up and

left town in 1954, leaving the Phillies with a monopoly. But

through the 1963 campaign, that club had never won a championship

in eighty-two years of trying.

The 1964 Phillies thus began their season with modest expectations.

The city was as surprised as the baseball world when the team

seized first place in July and proceeded to amass a sizeable

lead. Little known players like Johnny Callison, Richie Allen,

Ruben Amaro, and Cookie Rojas became local heroes overnight.

Manager Gene Mauch rose to deity status at the age of thirty-eight.

By mid-September, the pennant was at hand, and Philadelphia

glowed blissfully in anticipation of the rarest of events

– a World Series appearance.

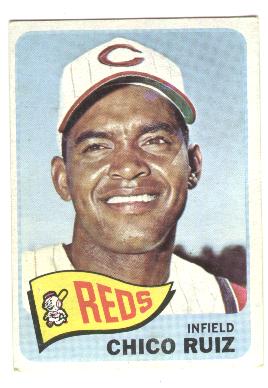

Then it all began to unravel. On September 21, the Phillies

held a comfortable 6.5-game margin in the standings and faced

the second-place Reds. In the sixth inning of a tie game,

Cincinnati rookie Hiraldo “Chico” Ruiz inexplicably

broke for home from third base with his team’s best

hitter at bat. Philadelphia pitcher Art Mahaffey was spooked

by the preposterous move, and threw the ball wildly. Ruiz

had stolen home, scoring what proved to be the game’s

only run.

The next day Ray Kelly of the Evening Bulletin wrote,

“It’s one of those things that simply isn’t

done. Nobody tries to steal home with a slugging great like

Frank Robinson at the plate. Not in the sixth inning of a

scoreless game.” He added, “Maybe that’s

why Chico Ruiz got away with it.”

Locals didn’t think much of it at the time, but after

Cincinnati won the next two games Philly fans began to boo

the home team. A sense of doom turned to panic as the Braves

came to town and swept four in a row. In seven days, the Phillies

had lost seven times and fallen to second place. The city

was in shock. The team went to St. Louis and lost three more,

completing the most infamous ten-game losing streak in baseball

history and cementing the wreckage of a once magical season.

The Phillies’ fall was the steepest ever for a first

place team so close to the finish line.

Philadelphia struggled to pick up the pieces. Since the Great

Depression, nothing had energized the city more than the Phillies’

run, and nothing disappointed a wider cross-section of the

population than the season’s ending. The collapse defied

analysis, though people tried. Many claimed that Mauch mishandled

his starting pitchers late in the season. Some believe that

dissension caused the team to disintegrate. Others held the

view that Ruiz somehow unleashed a pack of demons that consumed

the Phillies and a city that desperately wanted a winner.

Analysis of that fall’s events provides little support

for any of the three explanations, though the Ruiz gambit

has endured in Philadelphia folklore over the decades.

The previously anonymous infielder earned the wrath that fateful

night not only of Philadelphia manager Gene Mauch, but also

his own boss, Dick Sisler, and several teammates who saw his

move as reckless. The next night Mauch hounded Ruiz mercilessly

from the opposing dugout, and a Phillies pitcher planted a

fastball in his ribs. Ruiz responded with a home run. Even

though Philadelphia Inquirer reporter Allen Lewis

eerily foreshadowed a link between the stolen base and the

Phillies’ demise in the next morning’s paper,

the play was largely forgotten just two days later. The Phillies

uncovered many ways to lose games later that week, and each

catastrophe supplanted the previous one in short-term memory.

(Further, a bizarre and long-forgotten detail is that the

Phillies actually lost two games on consecutive days by way

of a steal of home – the other came at the hands of

the Dodgers’ Willie Davis in the wee hours of September

20.) The October post-mortem gave Ruiz a bit part in the drama,

but the stolen base provided concise and convenient imagery

of an otherwise incomprehensible sequence.

The legend gained traction as the Phillies immediately fell

into another dreary epoch. A deep bitterness took hold among

jilted townsfolk who, to paraphrase the words of devastated

backup catcher Gus Triandos, didn’t need to guzzle the

champagne that nearly every other major league city had tasted,

but rather just wanted a sip.

Philadelphia fans have since shown their vitriol on numerous

occasions. They’ve become known for mercilessly jeering

their own players, chasing more than a few promising but imperfect

stars out of town in the process. They’ve assaulted

opposing players and coaches. They once pelted Santa Claus

with snowballs in prime time.

After a blip of sports success in the late-‘70s and

early ‘80s, the fans’ frustrations have risen

with a steady crescendo of failures. The Phillies have flopped.

The hockey Flyers have come close, but stumbled. The basketball

‘76ers have ranged from awful to near-miss, and the

football Eagles have consistently tantalized before decomposing.

Whenever disaster strikes, local media invoke the legend of

Chico Ruiz. In one such occasion, after a postseason Eagles

meltdown in January of 2002, Philadelphia Daily News

reporter William Bunch put it all in context in an article

titled “Lets face it, losing is our forte.” He

started with two simple words – “Chico Ruiz,”

and wrote that Philadelphia “has now refined the art

of defeat the same way we once set standards for locomotives

and Stetson hats.”

Reflecting on the ’64 debacle in 1996, author Joe Queenan

explained a common feeling among Phillies fans: “This

was the pivotal event in my life. Nothing good that has ever

happened to me since then can make up for the disappointment

of that ruined season, and nothing bad that has happened since

then can even vaguely compare with the emotional devastation

wrought by that monstrous collapse.”

The sense of failure has spread beyond sports. Philadelphia

has struggled with ineptitude in other areas, as illustrated

by the city’s most prominent modern-day entry into national

headlines – a botched 1983 police operation that resulted

in the burning of an entire neighborhood. Surrealist filmmaker

David Lynch drew his inspiration from his days as a student

in Philadelphia, and called it “the sickest, most corrupt,

decaying, fear-ridden city imaginable.” That might be

a bit strong (after all, the city also has a well of urban

riches that make it the envy of many a sprawling American

community), but it reflects real and deeply rooted self-image

problems. Billboards peppering the city in the ‘70s

bore this out, declaring, “Philadelphia isn’t

as bad as Philadelphians say it is.”

More than most places, Philadelphia is defined by its history,

and the events of 1964 are a bigger part of it than most realize.

Four decades later, the city still bears the scars of a September

nightmare.

Ironically, Chico Ruiz stole only two bases over the next

two seasons and never hit another home run. He played in the

major leagues for eight years, amassing a mediocre .240 average.

He made the news twice more – first when he allegedly

brandished a gun at a teammate during a 1971 clubhouse argument

and finally when he died in a 1972 car accident at the age

of thirty-three. He achieved immortality in one spontaneous

moment, however, and remains better known on the streets of

Philadelphia than in his native Cuba.

As long as his memory lingers on those streets, a piece of

a city will be stuck in 1964.

September 2004

From guest contributor Scott Schaffer

|