|

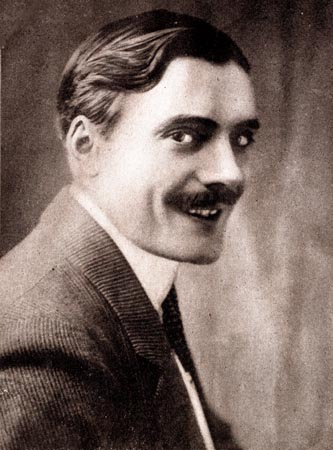

A short, elegantly coifed, mustachioed gentleman shuffles

into the room, a seemingly flawless and handsome example of

the French bourgeoisie in the early twentieth century. The

man, awkwardly shuffling, clumsily determined, dapper and

yet disarming, attempts to charm a lovely young woman, occasionally

succeeding.

One of the most successful comic actors of the silent film

era, Max Linder starred in several hundred films, most of

which he wrote and directed himself. In 1912, he was the highest

paid French actor in the world, making an incredible one million

francs that year.

In Republic of Images, Alan Williams refers to him

as “indeed the entire French cinema’s greatest

star of the prewar period." As David Cook explains in

A History of Narrative Film, Max “became world

famous for his subtle impersonation of an elegant but disaster-prone

man-about-town in prewar Paris." Despite his monumental

popularity on both sides of the Atlantic, today Linder is

relatively unknown to American film scholars and aficionados

alike.

Max Linder was born Gabriel-Maximilien Leuvielle on December

16th, 1883, in the small village of St. Loubes, Gironde, in

Bordeaux, France. His parents were grape farmers who supplied

many wine manufacturers and controlled a large vineyard, and

they wanted nothing more for Max than what he already knew,

but a career in grapes was the last among his goals. Max showed

an early penchant for the stage, and as a teenager he enrolled

in the Bordeaux Conservatory where he studied drama, eventually

performing in local theatre productions.

Max was doing what he loved, but he longed for the spotlight,

and a larger audience was necessary for his star to rise in

the way he knew that it would. While working at the Ambigu

theatre after moving to Paris in 1904, Max dropped his birth

name and started calling himself Max Linder.

While continually attempting to pass the entrance exam for

the Paris Conservatory (he failed the test at least three

times), Max landed his first roles via the extras casting

coordinator at the Ambigu, Louis Gasnier, who also happened

to direct films for Pathé, and quickly took a liking

to young Max and cast him in his first film, La Premiere Sortie

d’un collegien, or The School Boy’s First

Outing, in 1905.

Things appeared to be changing dramatically for Max when,

in 1907, he was chosen to fill a role made popular by a successful

comic actor known simply as Grehan after he left for another

studio. Williams states, “Linder was chosen to fill

Grehan’s shoes, as well as his evening coat, dress shirt,

and tie. Assuming the costume and much of the manner of Grehan’s

character ‘Gontran,’ Linder made, under Gasnier’s

direction, Les Debuts d’un patineur/Max Learns to

Skate (1907), the first work in which he becomes, recognizably,

‘Max’." Unfortunately, neither the real

Max nor the Max character made much of an impression, though

Linder stayed on with Pathé and worked on other projects.

Two years later, in 1909, Max reprised his version of Grehan’s

Gontran, and all of a sudden he was a star. Between the years

of 1909 and 1914, Max Linder made a film almost every two

weeks, and he rocketed into the position of the first real

international star of the cinema. According to Williams, “He

made tours of Spain, Russia, Germany, Eastern Europe. Everywhere

he was mobbed. Women were said to contemplate suicide at the

thought of his inaccessibility."

Max created one of the most memorable stage presences the

cinema had known in its short history. Most of his films,

as stated on the website Collector’s Homepage, “revolved

around the blameless bachelor Max who lives in luxury and

gets into funny situations because he is after a well-behaved,

pretty young lady."

Unlike some of his successors, like Mack Sennett, who relied

on an overt, exaggerated or a more “slapstick"

comic style, Max, according to Rick DeCroix in his article

“The Man in the Silk Hat," “specialized

in a more refined and subtle comedy mode. An early practitioner

of situation comedy, his films invariably concerned the uprooting

of social expectations and mores." In other words, Max

relied upon more reserved gestures and expressive facial expressions

than some of his contemporaries who pandered more overtly

to the camera. As Williams has commented, “Broad slapstick

would in any event have been out of place with the Max character,

a distracted bourgeois dandy played with a real sense of what

it meant to belong to the bourgeoisie."

A sort of all-purpose and moderately successful character

actor, once Max stepped into his version of Grehan’s

likeable, clumsy dandy, he had found his niche and never looked

back; Linder could easily be called the father of typecasting,

though he didn’t seem to mind. As the website Mugshots

argues, he “exemplified the French ideal of joie de

vie, always coming up smiling no matter what disaster befell

him."

The key to Max’s international, cross-cultural, and

class-transcending fame was his ability to make different

people laugh for different reasons. Though Max was always

impeccably dressed in the requisite tuxedo and tails, with

a top hat and a cane, all clear signifiers of the aristocracy,

his bumbling antics could interest anyone from a tramp to

a duke.

Linder had a real talent for holding the viewer’s attention

and making the most out of minimal sets and plots. In “Laugh

with Max Linder," Mark Zimmer explains that Max was

always “willing to milk a situation for all its worth

and then change locales to set up the next set of gags."

The bourgeoisie could laugh at him for being a misdirected

one of their own, constantly managing to get himself into

difficult and amusing situations, like in Le Chapeau de

Max (1913) when he is invited to a formal dinner, and

has an impossibly difficult time selecting and retaining the

perfect hat for the occasion, or in Seven Years Bad Luck

(1921), when Max breaks a mirror, and despite spending the

rest of the film attempting to avoid situations which would

cause him trouble, he still brings the worst kind of luck

upon himself. This film, one of Max’s most famous, features

a scene in which Max mimics himself in a mirror, a difficult

technical marvel that, filmed with a double, took an incredible

amount of time to rehearse, but some viewers still think of

it as the first and the best “broken mirror" scene

ever filmed. Zimmer comments, “Particularly notable

is the early sequence where his valet (who originally broke

the mirror himself) sets up the cook to mirror Max’s

every move in the frame. This gag was of course picked up

by others such as the Marx Brothers, but it’s fluently

pulled off here, with exquisite timing and very long takes

that must have required a great deal of effort to achieve."

Bourgeoisie viewers could relate to the situations and laugh

at Linder’s impropriety and inability to assimilate

properly, while working class and other viewers could simply

laugh at Linder’s good natured buffoonery, his character’s

tendency toward the bottle, and his weakness for attractive

young ladies. As Williams reminds us, most of Max’s

humor “springs from the conflict between Max’s

extreme self-confidence, as aspect of his social position,

and his incompetence at even the simplest tasks."

Linder influenced everyone from Mack Sennett, Buster Keaton,

Harold Lloyd, and Charlie Chaplin to Fatty Arbuckle, Abbot

and Costello, and The Three Stooges. “Although he expanded

and developed Max’s comic persona, Chaplin would borrow

virtually intact Linder’s restrained, minimal methods

in using the film medium, " Williams states. Indeed,

Chaplin paid homage to Linder on several occasions, both referring

to him as “my professor," as DeCroix explains,

and, according to the Collector’s Homepage, dedicating

at least one of his films to Max with this tribute: “For

the unique Max, the great master—his student Charles

Chaplin."

By 1910, Linder had been writing and supervising, and by 1911

also directing, all his own films. His popularity was at its

peak in 1914, when he went to war. Linder fought in the French

army for two years of World War I, and afterward his career

was never the same. He had been a victim of a German poisonous

gas attack, and his already slight constitution was irreversibly

affected. He returned briefly to French films, but finding

his popularity vanishing, he accepted an offer from Essanay

and moved to the US in 1916.

Continuous bad health affected the American phase of his career.

In mid-1917, after only three films, he got double pneumonia

and spent nearly a year recovering in a Swiss sanitarium.

When he returned to the US in 1921, he formed his own production

unit, releasing through United Artists. But after making only

three more American films, including the famous parody of

Fairbanks’ The Three Musketeers, The Three

Must-Get-Theres, he returned to Europe, where he married

the seventeen-year-old daughter of a Paris restaurateur in

1923, Jean Peters. Max was forty-years-old. Soon thereafter,

by many accounts, Max was sinking into a deep depression,

dealing with his fading stardom and his ill health.

In 1925, Max and his young bride poisoned themselves and slit

their wrists, leaving an infant daughter behind. Nearly forty

years after Max’s shocking death, his daughter, Maud

Linder, started a campaign to bring her father’s legacy

back to light. In 1963, Maud Linder wrote and directed a film

tribute to her father entitled En Compagnie de Max Linder,

also known as Laugh with Max Linder or Pop Goes

the Cork. This pseudo-documentary, nearly impossible

to find, was narrated by the legendary filmmaker, René

Clair, and features many clips of the great Linder, in his

element. However, the film received little attention, and

according to many critics, her efforts only deepened the mystery

surrounding the premature death of one of silent cinema’s

great artists.

Maud Linder was not satisfied with her work, and twenty years

later, she decided to make another attempt to honor her late

father on the big screen. In 1983, she released L’Homme

au chapeau de soie, or The Man in the Silk Hat.

This time Maude Linder wrote, directed, and narrated her documentary,

but to no avail. Though her second effort would not slip into

obscurity just as easily as her father or her previous film

had, it too received little notice, though cult fan groups

hoard it as the only “documentary" available on

the elusive Max. Unfortunately for those who wish to know

the real man, those who appreciate the truth, The Man

in the Silk Hat answers precious few tough questions.

As DeCroix tells us, “The Man in the Silk Hat

is a film with one main purpose: the resurrection of Max Linder’s

position in the film comedy pantheon. Obviously, it is a labor

of love, and therein lie certain obstacles. Always striving

to fulfill its goal, this documentary celebrates rather than

investigates. We learn much of Linder’s engaging screen

presence but little of his tormented private life."

DeCroix’s call for investigation is not unwarranted

but none have answered it. Few film scholars disagree with

the placement of Max Linder near the top the catalog of talented,

influential, and beloved comic actors, but his daughter’s

films seems to leave us wanting more. According to Maud herself,

“There was no real explanation for this tragedy [the

double suicide] and I never tried to find one."

Max Linder is compelling because of his talent and because

of his personal story. He rose from modest beginnings as a

grape-farmer’s son to become the greatest movie star

the world had ever known. He fought for his country, slowly

slipped in popularity, and died a shocking, mysterious death.

His films appealed to just about anyone who liked the cinema,

he influenced some of the most famous comedians of all time,

and now, shockingly, tragically, he is largely unknown.

November 2004

From guest contributor Chris Driver

|