Near the end of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Lorelie

Lee, played by Marilyn Monroe, turns to her fiance’s father,

Mr. Esmond, and explains why he should allow her to marry

his son. Her logic is impressive:

Don’t you know that a man being rich is like a

girl being pretty? You may not marry a girl just because she

is pretty, but, my goodness, doesn’t it help? And if you had

a daughter, wouldn’t you rather she didn’t marry a poor man?

You’d want her to have the most wonderful things in the world

and to be very happy. Oh, why is it wrong for me to have those

things?

Mr. Esmond is stunned by her persuasive argument, and he

stutters, “Well, I concede…," but here he interrupts himself

in dazed wonder, “Say…they told me you were stupid. You don’t

sound stupid to me." With a tender smile, Lorelie replies,

“I can be smart when I want to." Just like Lorelie Lee, Marilyn

Monroe could be smart when she wanted to. A careful look at

her life reveals that the dumb blonde stereotype is unfair;

Marilyn actually enacted the proto-feminism of what several

scholars have called the mid-century “transitional woman."

In the 1940s, when thousands of women flooded into the working

world, Norma Jean Dougherty took her place among them. Her

husband, Jim Dougherty, had been sent to the Pacific and Southeast

war zones as a Merchant Marine, and in 1944 Norma Jean went

to work at the Radioplane Company in Burbank spraying varnish

on fuselage fabric and inspecting parachutes. For this work,

she received “excellents" on the company evaluations and was

paid the national minimum wage: twenty dollars a week for

sixty hours of work. One day, a crew of photographers from

the Army’s First Picture Unit arrived at the plant to take

pictures of women contributing to the war effort.

Norma Jean’s fresh good looks made their way all over the

Army’s literature, and it was not long after that she quit

her job at Radioplane, realizing she had a future as a model.

Photographer after photographer attests to her professionalism.

More than any other model they worked with, Norma Jean was

relentlessly self-critical; she scrutinized contact sheets

and negatives for the tiniest fault; she asked her photographers

for advice. According to biographer Donald Spoto, she wanted

“every image of herself to be brilliant."

Her mother-in-law. Ethel Dougherty, did not approve of this

new career, so Norma Jean moved out of the house they were

sharing. She joined the Village School, a modeling agency

in Westwood, and by the spring of 1946 her hard work had landed

her on the cover of thirty-three magazines, including U.S.

Camera, Parade, and Glamorous Models.

Norma Jean, realizing she had that special luminescent quality,

decided she wanted to join the stable of starlets at Twentieth

Century-Fox Studios on Pico Boulevard. An unmarried woman

was more favorably regarded in this system, pregnancy during

filming could be very troublesome, so she quietly slipped

over to Las Vegas to get a divorce from Jim. According to

Gloria Steinem in Marilyn, Norma Jean was determined

and ambitious, and she was not going to let her arranged marriage

to Jim, who didn’t support her career choice anyway, keep

her from being successful in her chosen profession. She eventually

signed with Twentieth Century-Fox and was dubbed Marilyn Monroe.

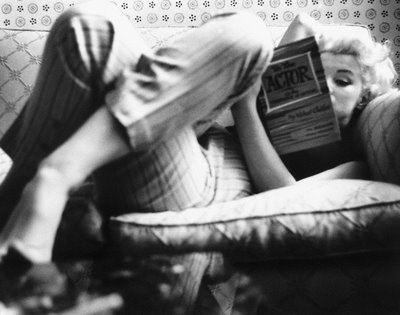

During her early years in the Hollywood system, Marilyn

worked hard to become a star. When the studio was failing

and did not renew her contract, she did not give up. She took

acting classes at the Actors Lab and did occasional modeling

work. When she was finally picked up by another studio, Columbia,

she added daily lessons with a drama coach, Natasha Lytess,

to her work load. Marilyn was never content to rely solely

on her looks. From her days at the Actors Lab until the day

she died, Marilyn was working with a drama coach.

At this point in her life, Marilyn met the executive vice-president

of the William Morris Agency, one of Hollywood’s most powerful

representatives, Johnny Hyde. They soon began an affair, and

Hyde repeatedly begged Marilyn to marry him, but she refused.

She had a single goal now: she wanted to be a star. She knew

that her marriage to a very wealthy man more than twice her

age would make her look like a bimbo and a joke which might

prevent her from achieving her goal.

Thus, in 1949, on the eve of the 1950s, the decade in which

women were leaving the workplace and returning to the domestic

sphere, Marilyn Monroe steadfastly refused to do so. On the

contrary, as 1950 approached, she could be seen jogging through

the service alleys in Beverly Hills each morning and lifting

weights to preserve her figure—two activities, as Spoto phrased

it, “not commonly undertaken by woman in 1950." She also enrolled

in an evening course in world literature at UCLA which she

attended in jeans—neither her college attendance nor her apparel

were commonplace at that particular historical moment.

After Marilyn re-signed with Twentieth Century-Fox, she

began taking acting lessons with Michael Chekhov, nephew of

the Russian playwright Anton Chekhov, and received her first

leading role in Don’t Bother to Knock. After this film,

her work in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and How to

Marry a Millionaire catapulted her to stardom, and in

1953 a photographer friend, Milton Green, suggested that she

start her own production company after he heard her complain

about the studio system — she was forced to play roles she

didn’t choose and was paid an absurd salary considering what

her films were making. So, in 1954, eager to change her image

from the sultry, dumb, gold-digging blonde and perform roles

with more depth, Marilyn Monroe defied the formidable Darryl

Zanuck, left Hollywood in the middle of her contractual obligation

to Twentieth Century-Fox, started her own production company,

Marilyn Monroe Productions, performed in a one-woman show

for soldiers in Korea, and settled in New York to learn what

she could by attending Broadway performances and studying

with Lee and Paula Strasberg at the Actors Studio.

During this period, her desire to change her image — perhaps

intensified by redoubled societal pressure to re-domesticate

“Rosie the Riveter" following the release of Dr. Alfred Kinsey’s

Sexual Behavior and the Human Female and the launching

of Hugh Hefner’s Playboy magazine (both in 1953) —

led Marilyn into her second marriage. She married Joe DiMaggio

who represented the wholesome, all-American, heroic image

she wanted herself. Unfortunately, this marriage did not last

long. He wanted her to retire, to wear less revealing clothing,

and to be an accommodating housewife. Spoto stated, “A traditionalist,

[DiMaggio] resented her income, fame and independence." When

she resisted the role he had designed for her, he became abusive.

By October of 1954, they were already separated with a divorce

pending. She would not give up her career, and she would not

endure an abusive husband.

During her time of growth in New York, Marilyn also read

widely and wrote poetry. The following is one of her better

works:

“To the Weeping Willow"

I stood beneath your limbs

And you flowered and finally

clung to me,

and when the wind struck with the earth

and sand—you clung to me.

Thinner than a cobweb I,

sheerer than any—

but it did attach itself

and held fast in strong winds

life—of which at singular times

I am both of your directions—

Somehow I remain hanging downward the most,

As both of your directions pull me.

Here Marilyn reveals her anguish over the contradictory

pushes and pulls between such issues as societal values, her

husbands’ demands, and her own desires. This contemplative

mood was a theme in New York; Marilyn was exploring her intellectual

side, the side that wrote poetry and attended serious theater,

and the second husband she chose, Arthur Miller, unveils her

need to change her image once again and align herself with

theater intellectuals.

In 1956, Marilyn Monroe Productions negotiated a contract

with Twentieth Century-Fox for its first project. Together,

they brought the hit Broadway play Bus Stop to the

screen. The lead role in this project was exactly the kind

of work Marilyn wanted to do.

The second project her company undertook was The Prince

and the Showgirl. For her leading man, she chose the most

“serious" actor in the world: Lawrence Olivier. She negotiated

a deal with Jack Warner, MCA, and Olivier’s production company

again in open defiance of Zanuck and Twentieth Century-Fox.

Indeed, Spoto has argued that the eventual “collapse of the

studio system and its ownership of actors owed much to her

tenacity and to the success of efforts exerted by her, Greene,

and his attorneys." Wisely, she also kept control of 51% of

MMP, so Greene, the attorneys, or Zanuck could not seize power.

On January 30, 1956, Time magazine announced, “There

is persuasive evidence that Marilyn Monroe is a shrewd businesswoman."

While filming The Prince and the Showgirl, Marilyn

earned the praise of one of the supporting actors, Dame Sybil

Thorndike. Thorndike was one of the legendary actresses of

the English stage, Shaw had even written St. Joan for

her decades earlier, and she saw talent in Marilyn. Several

weeks into filming, she tapped Olivier on the shoulder and

said, “You did well in that scene, Larry, but with Marilyn

up there, nobody will be watching you. Her manner and timing

are just too delicious…We need her desperately. She’s the

only one of us who really knows how to act in front of a camera."

Marilyn had worked with the best in the world and more than

held her own. Finally, in 1959, Marilyn’s talent was recognized

worldwide when she won her first major award—the Golden Globe

from the Foreign Press Association as best actress for Some

Like It Hot.

After filming The Misfits, Arthur Miller and Marilyn divorced. She was tired of financially supporting

the broke playwright and insulted by the role he had written

for her in that film. In one scene, Roslyn, Marilyn’s character,

expressed her dismay over the imminent slaughter of horses

by throwing a tantrum. Marilyn commented:

I guess they thought I was too dumb to explain anything,

so I have a fit — a screaming, crazy fit. I mean nuts.

And to think, Arthur did this to me. He was supposed to

be writing this for me, but he says it’s his movie. I don’t

think heeven wanted me in it.

Marilyn was also insulted by the film’s director, John Huston,

who treated her like an idiot and always addressed her as

“dear." Thus, in 1962, the independent Marilyn moved back

to Los Angeles by herself and bought her own home at 12305

Fifth Helena Drive in Brentwood for $77, 500. Unfortunately,

Marilyn died that same year.

For decades, irresponsible biographers like Norman Mailer

have represented Marilyn Monroe as nothing more than weak,

psychotic, junkie, nymphomaniac, idiot. I have tried to read

her life in a different way. True, Marilyn was sometimes mired

in the ideology of the past: she married men to gain an identity

she wished for herself; she was over-reliant on her sexuality

for success in her career. But, at the same time, she displayed

real agency by divorcing three unsupportive husbands who interfered

with her career and her self-esteem, by fighting for her modeling

and film success, by continuing to perfect her art by taking

acting classes long after she was a big star, by battling

Darryl Zanuck to have more control over her own destiny, by

starting her own production company, by buying her own home,

even by jogging through service alleys, lifting weights, and

wearing jeans. All of these things were accomplished six years

before the first feminist protest at the Miss American Pageant

in Atlantic City, New Jersey, and eight years before the First

Congress to unite Women in New York.

In his book, Graham McCann quotes Ella Fitzgerald saying

that Marilyn “was an unusual woman — a little ahead of her

times" after Marilyn fought with the owner of the Mocambo

Club to let Fitzgerald sing. In the 1950s, Hollywood nightclubs

did not invite non-white artists to perform. When Marilyn

learned that her idol had been denied any discussion of an

engagement at this club, she phoned the owner of the club

and told him that if he booked Fitzgerald, she would take

a front table every night. With this move, Marilyn placed

herself on the cutting edge of civil rights. Fitzgerald was

booked, and Marilyn was indeed at that front table every night.

Marilyn was able to transcend many of the traditional boundaries

of her era and display the proto-feminism of the “transitional

woman." Also, her actions reveal a person who was far more

than the dumb blonde she often played in films. Anthony Summers

tells the story in his book Goddess, when asked if

her friend was dumb, the actress Shelley Winters replied,

“Dumb? Like a fox was my friend Marilyn." As the biographers

of the future sort the distortions from the facts about Marilyn’s

life, I have a feeling they may be left like Mr. Esmond at

the end of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes saying in dazed

wonder to the spirit of Marilyn Monroe, “Say…they told me

you were stupid. You don’t sound stupid to me."

March 2003

|