The Boogeyman is real, and he has come out of the Dark and taken the Boy. The toys, who love and are loyal to the child, follow him into the dark to save him. As this point, one can easily fall back on common tropes of the subset of Children’s Literature commonly referred to as “Toy Fantasy" and guess what happens next. The Stuff of Legend, story by Mike Raicht and Brian Smith, with stunning pencil illustrations by Charles Paul Wilson III, designed and colored by Jon Conkling and Michael DeVito, takes these comforting tropes and explodes them, leaving readers in a truly postmodern narrative. The Stuff of Legend works on the toy-trope knowledge of its older audience, delivering something refreshingly, and sometimes shockingly, new.

Toy tropes were first established in early toy narratives, invariably children’s books, and gelled for more modern audiences in picture books, comic strips, and films. They work on several basic, natural childhood fantasies. First, that these objects that are designed to look like little people and animals have the capacity to act like little people and animals. The child, who loves his or her toys, must be loved in return. Toys aspire to please or serve their child, and the child is the center, leader, or god of this miniature world. The child, usually not a leader, center, or decision maker in his or her own life, is all of these very satisfying things in the world of his or her toys. With toys, the child becomes the adult.

In earlier toy literature, toys are largely passive – in Hitty: Her First Hundred Years by Rachel Field (1846) and Johnny Gruelle’s The Raggedy Ann Stories (1918), dolls live through battering, loss, and passively experienced adventures, accepting battering as “the price not only of love but of life," as Allyson Booth explains. Other, notably male toys, including William’s The Velveteen Rabbit (1922) and Collodi’s Pinocchio (1880) aspire to be real, finding their toys-ness not the gateway to adventures, as with Hitty and Raggedy Ann, but as a constraint to a full and fulfilling life. In their cases, their wishes to be real – a parallel to the child’s wish to be grown-up - are granted, as a result of external love, proof of their worthiness, and subsequent magical intervention. Again, a satisfying parallel to a child’s perception of how to grow up.

A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh (1926), E.T.A. Hoffman’s The Nutcracker (1816), and Lynn Reid Banks’s The Indian in the Cupboard (1980) pull from a different aspect of toy fantasy – that is, toys are a conduit to a special, secret world. In this world, the child is a central and powerful figure, able to change and often improve the lives of the anthropomorphized toys. The books empower children by portraying them as having power over something – the lives and actions of their toys. In Winnie-the-Pooh and The House at Pooh Corner, especially, Christopher Robin appears as the only sane and reasonable person, a proxy parent, in the lives of the “large dysfunctional family" that are his toys – which David Russell describes as “a hyperactive tiger, a manic-depressive donkey, a paranoid pig, a dyslexic owl, and a feeble-minded bear." Christopher Robin is often placed as the mentor and savior – “Here comes Christopher Robin – he’ll know what to do." The heroism and control of Robin, who is drawn physically larger (adult-sized) in comparison with his toys, as well as the wholesomeness idyll of the Hundred Acre Wood, have made the Pooh books a perennial favorite.

With Disney-ization and/or modern adaptation of these classics, a set of tropes starts to emerge. Toy tropes are developed and reinforced through the mid-twentieth-century by picture books like Don Freeman’s Corduroy, Peter Collington’s The Midnight Circus, and James Stevenson’s The Night After Christmas; longer books such as Russell Hoban’s The Mouse and His Child (1967) and Rumer Godden’s The Story of Holly and Ivy (1958); and television specials such as Rudolf, the Red-Nosed Reindeer – where he goes to the Island of Misfit Toys.

Toy tropes are thus fully engaged by the modern and most mass-produced of the toy narratives: the Toy Story films (1995, 1999, 2010) and Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes (1985-1995). Audiences, then, are fluent in “toy rules." First and foremost, toys exist to serve the child. They are a family or group, with individual identities and skills, and a common goal: be the child’s playthings and love the child as much as the child loves them. As with any group, there may be friction in the ranks, but it is usually minor. In the commentary on the DVD of the first Toy Story movie, the writers explain how the group of toys act as if they are actually at work. They have meetings and tasks, which Woody, as leader, runs and assigns. The toy that is the child’s favorite, such as Woody, is the leader of the group or, as in Pooh, is the central figure of the narrative.

Toys have a life beyond the life of the child, whether the child is aware of this life, as in Winnie-the-Pooh, or is not, as in Toy Story. Generally, when the toys are alone, they feign to be or are forced to be inanimate. Usually this in presented in the form of rules or laws. Calvin and Hobbes straddles a line here. Hobbes is a full tiger to Calvin, and a toy tiger to everyone else.

Threats to the toy’s or the child’s happiness or well-being similarly fall into established tropes. These threats inevitably mirror an average child’s anxieties. Major threats include the loss, either of the child, as in the Velveteen Rabbit, or the loss or misplacement of the toys themselves, as in Toy Story. The outside or unfamiliar world, is also a threat, firmly established in all the Toy Story films, whether it be moving day or an insane daycare center. Furthermore, parents who don’t understand the value of the toy to the child, or the child outgrowing his or her toys (Toy Story 3), are a persistent threat, mirroring growing-up anxieties. Other children who don’t see the value of the toys, especially girls, such as Susie Derkins in Calvin and Hobbes or Sid’s sister in Toy Story – both of whom demasculinize a male toy by forcing it into the inevitable tea-party - threaten the well-being of a toy. Dogs, as well, whether they be the new Christmas puppy or Sid’s vicious mongrel tend to threaten the toy, either by innocent roughhousing or by intentional targeting.

The ultimate threat to a toy is, of course, being replaced. Buzz threatens this in Toy Story, and the Velveteen Rabbit, as well-loved as he is, is tossed in the bin and forgotten by the child, who gets a new rabbit and a trip to the sea-side.

The Stuff of Legend takes these tropes, and other more subtle staples of toy fantasy narrative, and explodes them, using the reader’s expectations of what toys can do and how toys can act, and either going beyond or subverting these expectations.

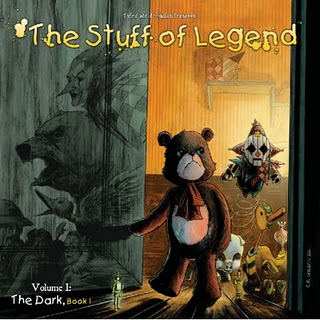

“The Boy," referred to as such throughout the six so-far-published issues, lives in Brooklyn in 1944. His father is fighting in Europe, and he, his younger brother Johnny, and his female relations have been left behind. Through a series of flashbacks, the reader comes to understand that Max, the Teddy Bear, is the favorite toy, though the Colonel, a toy soldier, has recently become favored as well, mimicking the boy’s sense of the war, as the colonel fights his way to the tops of hills to rescue the Indian Princess. The boy has recently gotten a puppy – much to the toys’ discomfort. Then one night, from the dark of the closet, the tentacles of the Boogeyman reach through and take the boy into the Dark. The toys, inanimate and helpless when the boy is awake, quickly mobilize. The Colonel, Max the bear, Quackers the toy duck, the Indian Princess, Harmony the ballerina-top, Percy the Piggy Bank, and Jester, the slightly insane Jack-in-the-Box, go into the Dark to look for their child. Scout, the boy’s puppy, comes right along.

A turn of the page reveals a break from one of the most familiar tropes of toy literature. When toys become animate, they generally keep most attributes of their toy selves: size, temperament, and/or appearance. Hobbes is more tigerish in Calvin’s imagination, and Pooh and friends are slightly more real versions of their cuddly selves. Woody and company are physically identical to their inanimate selves – the toy soldiers must manage walking on their static plastic bases. What happens in The Stuff of Legend to a toy in the Dark is jarring. All the toys become full-life-sized version of their toy selves – Max is a grizzly, the Princess a knife-wielding warrior, and the Jester has hatchets. The tiny toy Colonel becomes a full-sized soldier – one that bears a striking resemblance to the boy’s father.

Where most toy narratives work on perceived danger (sure, Sid threatens to blow up Buzz Lightyear, but we sort of all know it’s not going to happen), The Stuff of Legend wastes no time in making clear that these toys are in true danger, and they are physically capable of facing it. The Boogeyman’s forces, a range of discarded and now-anthropomorphized toys, complete with guns, swords, and other weapons, are a true and bloody danger – perhaps an echo of a boy’s idea of who or what his father must be fighting.

The Boy’s toys are strong warriors, for the most part, though Harmony is too tender-hearted for battle, and Percy too cowardly. Each of the toys, as with most toy narratives, are imbued with the attributes of both their physical forms - Max has the teeth and claws like a bear; Quackers can fly like a duck - and of the attributes the Boy has given them – the Colonel is Brave; Harmony is sweet. Unlike other toy narratives, however, the attributes are not distributed equally. The level of “real-ness" that the toys have in the Dark, is proportionate to the amount to life, time, and thought the boy has given them. Harmony, not much played with, looks mechanical. The Colonel, fully real. The toy train-men, who admit they were thrown in the closet before being taken out of the box, the least real.

Furthermore, the more time they spend in the other-world of the Dark, the more these toys grow and develop into their own personalities. The Jester, at first wacky and whimsical, even with the hatchets, is straight-up-bloodthirsty by the end of the second volume. Percy the pig, who is intelligent but skittish to begin with - having spent his life as a piggybank leads to a terror of being dropped and broken – becomes not only a coward but a conniving betrayer. The Princess, strong, proud, and distant, becomes more assertive and more vibrant. In other words, the longer they are in the Dark, the more real these toys become – with no contact whatsoever with their boy. And with no overt discussion of “realness." To be a real boy, to be a real rabbit, is never an aspiration as it is with Pinocchio and the Velveteen Rabbit. In the Dark, it would seem, realness is compulsory. In the Boy’s world, inanimateness is a limiting, but not necessarily unfavorable condition. Indeed, Harmony seems to remember the stillness of the Boy’s world wistfully, in the face of the violent and dangerous Dark.

When, in toy narratives, the child's toys meet “other" toys, that is, toys not belonging to the child, these other toys are usually friendly – even if they are first perceived as threatening, as with Sid’s mutant toys in Toy Story. In Toy Story 2, Stinky Pete tears Woody’s arm, but it doesn’t seem to hurt. In Toy Story 3, the daycare center toys are organized and do form a true nemesis force; they have the power to entrap the hero toys, but not to harm them.

In The Stuff of Legend, the other toys are not only a direct and violent threat, but different kinds of toys pose different threats. The residents of Hopscotch, a town designed around a maniacal and unfair board game, live their lives by bizarre and capricious rules, forced on them by a megalomaniacal Mayor – also a minion of the Boogeyman. In the Jungle, the real-ness of the toys moves a significant step further – the animal toys have lived in the Dark of the Jungle for so long that they refuse to call themselves toys – not because a Blue Fairy or enough love has made them “real," but because the Boogeyman has instilled in them a hatred of all things human. To belong to a human and be its plaything has become disgusting to the animals of the Jungle. Human toys are hunted for sport by the animals, who care nothing for their common origin. The most terrifying “other" toy, a destroyer of Boogeyman - and good-guy forces alike - are the mindless golems – clay shapes bent on simple destruction. This stratification and differentiation of toy types allow a level of complexity of narrative – who is friend? who is foe? and who switched sides a long time ago? – absent from earlier, simple toy narratives.

Also absent from most toy narratives is a clear, named, and shown foe. Vague outside threats may shake a toy community from time to time – a new toy, a new puppy, a blustery day. Even Toy Story’s Sid, the crazed toy-destroyer next door, can, with the right gaze, be seen as more of a misguided mad scientist. But the Boogeyman is real, is insidious, and is, apparently, everywhere. The Boogeyman can easily be a metaphor working with the time and setting of the story – an America in 1944 was a mass of fears of vague yet palpable threats: the Boogeyman is Hitler, is the German spy next door, is the possibility that the letter from dad is the last the Boy will ever receive. There is comfort in a metaphoric Boogeyman – but this Boogeyman is named and shown, and he relentlessly and tirelessly pursues our heroes. Most significantly, he is a threat to the real boy in the real world as much as he is a threat to the toys in the Dark. The excuses that the reader instinctively makes – the Boogeyman somehow is not really a threat, the boy is actually safe somewhere, this is his dream, or maybe the Boogeyman is a manifestation of the Boy’s dark side/fears/social conditioning – all of these attempts at self-comfort are taken from the reader when we see the Boy in the Dark, alone, somewhere that the Boogeyman has trapped him. No toy narrative has so crossed the line from fantasy world to real world to the extent of truly endangering the toys’ child. The child is meant to be the savior, the god, and the hope and focus of his toys. Seeing the boy in the Dark pushes the reader into unfamiliar territory – the toys have made their sole focus finding the Boy. But once the reader sees this trapped Boy, the reader is forced to ask, what if his toys do find him? The Boy is, if anything, less capable of controlling the Dark and/or vanquishing the Boogeyman than his toys are.

Another toy trope that is almost immediately subverted is the presence of a hero/leader. The Colonel leads his little group into the Dark and through battle with the simple and clear goal of finding the Boy. But the Colonel, soon after entering the Dark, comes face-to-face with the Boogeyman himself. We have seen the Colonel, as the Boy plays with him, get to the top of the hill and defeat the foe. But, as the Boogeyman says, the Dark has different rules than the Boy’s world, and the Colonel has not learned them yet. Getting to the top of the hill, for example, is sometimes “only the beginning of the fight." And so, before the first issue of The Stuff of Legend ends, the leader is destroyed. The other toys decide to soldier on, Max taking the lead, but the death of the Colonel decisively shows the reader that this is a world in which no toy is safe.

With the death of the leader comes the natural confusion of whether the toys should go on or go back. Of course, they go on, but under the shadow of yet another broken toy narrative trope. Toy narratives will have sometimes have minor or perceived betrayals. Hobbes takes endless joy in tricking and pouncing on Calvin when Calvin least suspects it. In the first Toy Story movie, Woody is rejected by the other toys when they think, wrongly, that Woody has done away with Buzz out of jealousy. Pooh and Piglet steal Eeyore’s house – an honest mistake. But The Stuff of Legend works on not one but two levels of betrayal.

Percy the Pig, never keen on this quest to begin with, is found by the Boogeyman and is quick to agree to work for the him. The Boogeyman capitalizes on Percy’s fear of being broken, a fate that will surely befall Percy as soon as the boy saves enough money. In the Dark, as a flesh-and-blood pig, Percy is safe, and when the Boogeyman offers his protection, Percy willingly agrees to delay or turn back the other toys. After, through his inaction, he contributes to the Colonel’s death; Percy, with the help of the Boogeyman’s allies, succeeds, by the end of the most recent issue, in pushing the group past the breaking point, scattering the various members away from Max, the Teddy/Grizzly bear.

A final, and perhaps the most powerful of the toy tropes, centers on Max. Almost every toy narrative includes some level of replacement anxiety. This comes in many forms – the child may be moving on to more mature times, as in Toy Story 3 and The House at Pooh Corner. The toy may be defective in some way, as in Corduroy or The Velveteen Rabbit. Even Hobbes has to go in the washing machine from time to time. But the most common incarnation of this replacement anxiety is a favored toy being replaced by a newer thing, losing the favor of the child, who is, for the toy, the center of existence. Buzz Lightyear threatens Woody. Jessie the Cowgirl is left behind in favor of teen-girl concerns. The Island of Misfit Toys is populated by toys which each have a correlating, better version – the Charlie-in-the-Box, for example. S.D. Schindler’s picture book The Curious Island of Abandoned Toys makes it clear that inhabitants, politely, do not ask how other toys ended up there. To be abandoned is not only a source of pain, but a source of shame. The toy has somehow failed its owner. If, as the King of the Island of Misfit Toys says, “a toy is never truly happy until it is loved by a child," then it follows that a toy is in despair if it does not have a child’s love. The universality of this trope speaks to its strength, as most children, as some point, feel this replacement anxiety themselves. “Toy" is to “child" as “child" is to “parent." A child may feel not-good-enough in the eyes of their parent, or threatened by the arrival of a younger sibling, or fearful of the loss of a parent to separation or death.

This replacement anxiety is the chief motivating factor in Percy’s betrayal, as Percy has heard the Boy looking forward to destroying his Piggy Bank. But the strongest replacement anxiety comes with the toy that is the favorite, and who has the most to lose – Max. It is logical that a toy that is best loved has the most to lose in the loss of that love. Max, we learn, had replaced the boy’s first favorite toy, Monty the cymbal-monkey. Monty was greeted in the Dark by the Boogeyman, who then was showing a kind face, comforting the displaced Monty, and other discarded toys. The Boogeyman also tempted and won the allegiance of the Knight, another favorite who suffered the terrifying toy-fate of being lost. But Max was most threatened by the Boy’s new puppy, Scout, “the toy that could play back." When Scout takes Max’s place on the Boy’s bed, and Max is left on the floor, the Boogeyman starts to whisper to the despairing Max. The Boogeyman successfully tempts Max into opening the closet door just enough. Max thinks the puppy will be taken, but it is the Boy the Boogeyman wants. The replacement anxiety over the puppy drives Max to rash and destructive action, which he spends the balance of the books trying to correct.

In The Stuff of Legend, interestingly, at the end of the most recently published book, it is not so much the toy that has been replaced in the eyes of the child, but the child – or the quest for the child, that is replaced in the eyes of the toys. The ultimate trope is ultimately subverted. With the knowledge of Max’s betrayal, and inflamed by Percy, the group of toys falls apart. Their single-minded focus on the Boy has fallen apart as well. Max has won the place of King of the Animals, and the only one to stay by his side is, ironically, Scout the puppy. The Princess is injured in the Jungle, and Jester, who has become enamored of her, leaves Max to find her again. Harmony follows, having bonded with the human toys through the animals’ hunting of them. She is ready to return home, and abandon the quest for the boy, having “endured enough." Quackers, angry and disgusted, leaves with Percy, his trust of Max shattered. Max, the favorite toy, is left alone and broken, still wishing to search for the Boy, but convinced he cannot succeed without his friends. The loss of his friends, the toys, hurts him more deeply, it seems, than the loss of his Boy.

The establishment of toy tropes in children’s literature reflects the needs and interests of the children for whom that literature is made. Children’s own fears, fantasies, and worldviews are played out by their toys when their toys come to life in their stories. The Stuff of Legend quite skillfully takes the tropes with which its grown readers are already intimately familiar and subverts or expands on them, leading the reader to a fresh, surprising world, both familiar and unpredictable.

January 2012

From guest contributor Rebecca Gorman O'Neill, Associate Professor of English at the Metropolitan State College of Denver

|