|

I’m a perfectionist. As far back as

I can remember I’ve always been neat, tidy, and organized.

Since the age of five I’ve made my bed every morning

and folded my own laundry. While other kids were racing their

bikes,

I was rearranging my desk drawers and wrestling with furniture

in a pre-school, Feng Shui trance. Even now, at the age of

thirty, I make sure all my appliances are turned off before

I leave my house. I shudder to see creases in my bedspread,

and I’ve been known to drive down the street after

locking my front door, only to return ten minutes later and

rattle the doorknob another five times. All the hangars in

my closet must face the right direction, books are pushed

back against the shelves, tallest to shortest, and my DVD

collection is alphabetized.

I crave structure. I crave order. In my mind, life has a

clear and definite path, whether it is school, family, or

a personal relationship. When conversations go astray, when

plans develop kinks, I become anxious and nervous, choking

on panic like a dog on small bones. I need constancy. I need

stability. And perhaps this is why I’ve always loved

Walt Disney films, those vibrant fairy tales that pulse with

clear distinctions between good and evil, characters that

act according to their designated social standings, and endings

that celebrate eternal happiness for fortunate souls who

work hard and embrace positive values. As a child, Disney

films comforted me with their predictable formula. There

was never any doubt that Cinderella would go to the ball;

there was never any doubt that Dumbo would earn the respect

he deserved. Good always triumphed over evil, and every ending

radiated with consumer glee and happiness. Disney films filled

my childhood with Technicolor dreams, and I smiled as realism

succumbed to romance in the wake of catchy songs and never-ending

rainbows.

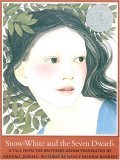

In the spectrum of Walt Disney characters, I’ve always

admired Snow White. It’s not her ravishing beauty,

or her ability to charm the animals. It’s not her undying

patience with the seven dwarfs or her porn-star voice that

crackles with girlish innocence. What I’ve loved about

Snow White is her dedication to housework, and her compulsive

need for organization! No matter how many times I watched

Disney’s version of the classic fairy-tale, she ignited

my passion for order when she waltzed into the dwarfs’ house,

set her hands on her hips, and proceeded to sweep the floor,

wash the clothes, dust the cobwebs, and cook a full course

dinner. She acted with a purpose, and I respected that. Plus,

she performed her work with such style and zeal, especially

after escaping from a murderous hunter and fleeing for her

life through a dark and menacing forest.

Recently, however, after rewatching Snow White and the

Seven Dwarfs, I realize how misogynistic the film is when compared

to the original story. That necessity for organization, which

I always admired, now seems more of a feminine requirement

than a fully realized attempt to create order in the world.

The original fairy tale by the Brothers Grimm is a battle

between good and evil, peppered with morals; it concerns

the theme of female jealousy, specifically an older woman’s

vicious jealousy toward the youth and beauty of a younger

one. The original fairy tale is a woman’s story that

reflects female fears, the major one being that a woman’s

worth is based on her beauty and appearance.

The 1937 film, however, is a thinly-disguised promo that

advertises women as “the angel in the house." Walt

Disney transformed a timeless fairy tale about jealousy and

innocence into an animated love story in which the male gender

is yet again superior and dominant over the female gender.

Disney has refocused the story to revolve around Snow White’s

womanhood and her yearning for Prince Charming, the man of

her dreams. This approach departs from traditional fairy

tales, which, as Iona and Peter Opie state in their introduction

to The Classic Fairy Tales, “are more concerned with

situation than with character." In a traditional fairy

tale the time period is irrelevant, characters are often

flat and one-dimensional, and endings are often unhappy.

Such fairy tales often contain excessive violence, an impending

sense of gloom, and continual suspense. Indeed, after reading

many traditional fairy tales, especially those by the Brothers

Grimm, we can see a thread of Gothicism that contributes

to the tales’ gruesome actions and somber atmosphere.

As regards the story of Snow White, both mediums (the original

fairy tale and the film version) employ the gothic to emphasize

their morals. In examining the two mediums, especially Disney’s

film, we must consider the relationship between gender and

the gothic. The typical gothic situation involves the pursuit

of innocence, usually in a romanticized female form, by evil,

usually represented by an evil male who hides in his phallocentric

castle and excels at sexual harassment. In the gothic novel,

female innocence typically wins out over male dominance.

Male villains in gothic fiction do not usually respect the

woman, which illustrates the point of view that many women

often expressed, especially those trapped within a male-dominated

audience and culture during the Romantic era when the gothic

novel flourished. For women, the gothic novel reinforced

their submissive role in society, but it also liberated them

from such roles by creating feminine heroes who triumphed

over their male oppressors. Obviously, Snow White

and the Seven Dwarfs differs from many gothic stories

in that Snow White is not being threatened by a man, but

by a woman, namely her evil stepmother.

In the 1937 Disney film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,

the gothic is not just being used to express women’s

sense of imprisonment. While the original story of Snow White

is often ambivalent to gender, and uses the gothic simply

to illustrate the macabre results that often accompany evil

deeds, the Disney film employs a domesticated, didactic gothic

that designates boundaries where women are safe and unsafe,

where they are placed into feminine roles. The film begins

with a gothic atmosphere in which the queen consults her

magic mirror. The mirror represents the inner voice of the

narcissistic queen, a woman who treasures attractiveness

like an Avon consultant. Yet the mirror also represents the

voice of society, a population consumed by beauty and perfection,

and it is no mistake that the mirror’s voice is masculine.

This scene is steeped in blacks and reds, emphasizing the

queen’s villainy and malicious intents. Even the queen

herself appears gothic, sporting well-curved eyebrows, a

gaunt face, and high cheekbones. Brenda Ayers believes the

queen seems wicked because “she is not part of a family

enclosure; and her own house, a castle full of skeletons,

spider webs, and rats, represents a home deprived of domesticity." After

the queen learns she’s lost her title as the fairest

woman in the land, the film then cuts away to reveal the

viewer’s first glimpse of Snow White, a young child

who hums and sings while she performs menial labor. The colors

in this scene are bright and vibrant, a collection of whites,

yellows and greens. In contrast to the queen, Snow White

has rosy cheeks and a round face; she appears virginal and

doll-like. As she scrubs the castle steps and fetches water

from a well, the camera cuts to multiple close-ups of her

beaming face, thus implying that not only do women love to

perform such mundane household functions, but also that to

dress in tatty rags and haul heavy buckets under a hot sun

is pure domestic bliss.

Any child who watches Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs will

understand that the first two scenes are complete opposites.

One involves an evil queen fuming in a dark and gloomy part

of the castle; the other involves a beautiful girl who sings

and smiles while working outside in the dazzling sun. This

dichotomy prepares viewers for the film’s gothic elements

and also relays an important message: women are happiest

while working in a domestic element. As the scene suggests,

the bright colors create a sense of relaxation and contentment,

a sense of safety. The gothic elements, however, represent

those distant lands and opportunities that women should not

cross; Disney’s message is that the unknown harbors

countless dangers, and also that women would do well not

to stray too far on their own, away from security and masculine

protection. In Walt Disney’s Snow White and the

Seven Dwarfs, the gothic thus becomes a hindrance to a woman’s

happiness and familial obligations.

Looking into the well, Snow White sings, “I’m

wishing for the one I love to find me today." Suddenly,

Prince Charming appears, suggesting to children that not

only can wishes come true, but only the male gender can supply

them. As Snow White listens to the Prince sing his deepest

affections for her, a flight of doves congregate on her body

and fly into the air as though participants at a mock wedding.

These doves symbolize peace and love, and when one of them

lands on Prince Charming’s hand, it blushes coyly at

his chivalric stance and musical talent. This connection

between the Prince and the dove suggests that nature also

has a plan for Snow White; not only does society expect her

to marry the Prince and remain a faithful and obedient wife,

but nature does, as well, thus illustrating that a woman’s

place in society is not only cultural, but intrinsic and

habitual. Naomi Wood reflects on this mix of humor and social

values, writing, “On a psychological level I believe

that Disney’s popularity is in part based on the way

his movies explore the dynamic between controlled domestic

moralism on the one hand and chaotic ‘gags,’ ‘sexual

perversity,’ and polymorphous perversity on the other." The

cooing doves add romance and purity to the burgeoning love

story, yet a subliminal message hints that every woman needs

to be saved. Should the viewer assume that in order for Snow

White to have a happy future she needs to make a wish?

There are many elements of magic in Snow White and the

Seven Dwarfs, but their main role is to foster the love story that

Disney suggests is so important to the creation of the standard

American family, which, in 1937, required the submissive

wife to stay home and clean while the knowledgeable husband

dashed off to work like a gallant knight. Folklorist Kay

Stone believes that Disney “Americanizes" fairy

tales “by making the heroines and heroes more interesting,

adding humor, subtracting magic, and downplaying royalty." This “Americanization" of

the original tale, as Stone suggests, also implies that women

need a man to fulfill their happiness, and that man alone

can supply the magic and romance that so many women desire.

This idea promotes the male gender to a higher position of

power and awe, one that also implies dominance. That Snow

White resembles a doll also adheres to the film’s presentation

of her as an object who must constantly acquiesce to masculine

desires.

The original bestselling fairy tale by the Brothers Grimm

is quite short. The text announces Snow White’s birth,

her evil stepmother entering her life, and the importance

of the magic mirror in just a few short paragraphs. These

are situations that set up the story’s themes of innocence

and jealousy. The characters themselves do not develop and

grow in the traditional narrative sense; they are mere caricatures,

representative of the same emotions that reside in all human

beings. Also, in the fairy tale, the queen orders the huntsman

to kill Snow White and then return with her lung and liver.

Anticipating Hannibal Lector by at least one hundred years,

the queen salts the organs and devours them. The tale’s

focus on the lung and liver corresponds with the scientific

trend at that point in history, during which many scientists

believed that while the lungs supplied the body’s necessary

breaths, the liver was the principal organ of the human body

and developed first among all organs. At that time, many

scientists believed it was the liver, and not the heart,

where blood was formed, and thus the liver was the center

of the body’s circulation. By eating the lung and liver

of Snow White, the queen symbolically ingests the girl’s

life while also triumphing as the dominant woman, all so

she can simply cancel out the serious threat to her beauty

and happiness that Snow White unknowingly represents.

In the Disney film, however, the queen requests Snow White’s

heart instead of her lung and liver. This change makes sense

when we consider that Walt Disney wished to create a love

story and focus the film’s attention on domesticity.

That the queen is unable to have Snow White’s heart

fits better in the film because her heart is only meant for

Prince Charming. The queen, surrounded in her dungeon by

spiders and cobwebs, and ensconced in perpetual gloom, does

not deserve a man’s heart or his love. Here, the film

suggests that women who deprive themselves of a domestic

lifestyle will find themselves unable to develop and sustain

loving relationships. Like the queen, they will spend their

days angry and lonely, banished from all the familial responsibilities

and household chores that Walt Disney implies so many women

should yearn for as children. We must also remember the ancient

belief that eating the heart of an enemy makes a person stronger.

Clearly, the queen wishes to gain Snow White’s energy

and beauty, as well as the constant adoration Snow White

receives from her many admirers. It is this jealousy that

drives Snow White from her bubble of domestic bliss and into

the unknown gothic that symbolizes not only her independence,

but also her much-needed adolescence.

Reflecting on the film, I have to question whether my interest

in Snow White lies in my own private yearning for a fairy

tale romance. Certainly, some might label me a misogynist,

their claim being that because I admire Snow White I must

therefore desire a woman who lives in the kitchen and treats

me like a monarch. But the honest truth is that I see myself

in Snow White, not simply as the compulsive organizer who

cleans house, but as someone who craves a perfect future.

It is important to remember that readers do not always identify

with characters along gender lines. Also, I understand Snow

White’s emotions when she stands over the well and

wishes for the man of her dreams. Every day I bask in famous

love scenes: the tragedy of Gone with the Wind and the ache

of Love Story, the sacrifice of Casablanca, the fatalism

of Romeo and Juliet. I realize that Disney films are part

of the “manufactured dreams" of classic Hollywood

cinema. I am a junkie for such manufactured dreams, coveting

scenes where kisses land squarely and words connect in symmetrical

meaning. These are snapshots of a life bursting with impracticalities,

numbing the ache of realism. Challenged by passion, like

my friend Snow White, I constantly duel with perfection.

Like Snow White, I remain out in the open, avoiding the gloomy

woods whenever possible.

Like me, Snow White flees the gothic because she believes

it will not nurture her dreams. In Disney’s film, her

dream is to shun independence and embrace marriage, thus

her desire for order and security cancels out any feelings

of female autonomy. I recognize that problem, and I understand

how we can become trapped in such a situation. The unknown

can be frightening because it often represents change. To

embark on a journey alone, whether it is physical or emotional,

requires courage and dedication. For a girl like Snow White,

who spends her days in a safe and secure world, aimlessly

performing chores, the idea of maturity can seem hostile

and unattractive. The gothic represents a world where Snow

White would have to think for herself, and Disney makes it

clear that women straying into such territory is detrimental

to both women and society as a whole. While both the story

and the film illustrate a fundamental need to escape the

gothic, the film version links it to domestic stability,

whereas the fairy tale illuminates aspects of the human condition,

mainly jealousy and wrath.

Snow White does not realize the gothic is a gateway to independence;

to suffer is to learn, and Snow White must therefore suffer

before she can escape the comfort and security to which she

clings mindlessly. According to modern psychology, and also

alluded to in the Brothers Grimm version of the tale, Snow

White must rely on herself and assert her independence if

she hopes for a bright future. Basically, she must find the

courage to leave all that is familiar so she can experience

her adolescence, which all children require before they can

move into adulthood. Alas, Disney never allows Snow White

the chance to taste such independence, surrounding her instead

with small mammals and dwarfs who desperately need motherly

affection. As Brenda Ayers states, “That Disney mirrors

a Victorian tale is to say that Disney also perpetuates a

nineteenth-century notion of domestic ideology: Women are

to be submissive, self-denying, modest, childlike, innocent,

industrious, maternal, and angelic – all traits that

perfectly describe Snow White." Thus, at the end of

the film, Snow White remains an innocent doll, simply transferring

owners from the queen to Prince Charming. It should also

be noted that throughout the entire film, Snow White remains

trapped within the confines of domesticity, moving from one

enclosure to another, from the castle to a house and finally

to a glass coffin. There she rests, suspended in childhood

animation until Prince Charming eventually claims her and

returns her to yet another castle where she will no doubt

rejoice among piles of dirty laundry and stone floors in

desperate need of scrubbing. Adolescent passion has now been

molded into domestic submission.

In the original tale, Snow White exudes passion when she

begs the huntsman to spare her life. She begs not only for

her life, but for the chance to create a stable future. In

the film, though, the huntsman, weakened by her innocence,

takes pity on Snow White and commands her to run away and

never return. In the fairy tale, Snow White’s begging

not only represents a desire to live, but it also suggests

she is capable of thinking for herself and forming rational

decisions. In the film, however, Disney implies that the

huntsman abandons his murderous act because Snow White is

a poor, defenseless woman. By taking away the scene where

she thinks for herself, Disney further objectifies Snow White.

This decision allows the viewer to better understand why

she becomes horrified in the dark forest and must then begin

a new life in a brightly-colored domestic setting where,

once again, she feels comfortable performing household chores.

Snow White’s frenzied run through the forest is one

of the film’s highlights, as it clearly emphasizes

that she is confused, alone, and scared when faced with the

possibility of independence. The forest in which Snow White

finds herself is a staple of Gothicism with its dense woods

and claustrophobic atmosphere. In his text Gothic, Fred Botting

emphasizes the effect that darkness often has on an individual: “Shadows

marked the limits necessary to the constitution of an enlightened

world. Darkness, metaphorically, threatened the light of

reason with what it did not know. Gloom cast perceptions

of formal order and unified design into obscurity; its uncertainty

generated both a sense of mystery and passions and emotions

alien to reason."

The dark forest stifles Snow White because it is unfamiliar

and represents the leap into adolescence she so desperately

needs to make. To accentuate the gothic, Disney imbues the

scene with black and dark blue colors; shapes are difficult

to discern, and this uncertainty creates in the viewer the

same sense of panic and paranoia that exists in Snow White.

The forest, with its tall trees and dark colors, is masculine;

nature there is hostile, as trees and bushes grasp violently

at her clothes, angered at her trespassing into a territory

that Disney suggests is not meant for the female gender.

Furthermore, Snow White’s bright yellow outfit contrasts

with the gothic forest, thus illustrating, yet again, that

she is out of place and not meant for independence. Disney’s

message is that Snow White is safe and happy so long as she

remains childlike and embedded in a domestic setting. She

can be associated with nature so long as that association

is feminine, clearly marked by her maternal instincts towards

the stampede of animals that follow her around like toilet

paper stuck to the bottom of a shoe.

Snow White’s submissive need for domesticity continues

throughout the film, especially after her flight through

the dark forest. Sad and anxious, panicked and lost, the

most obvious remedy is to arrive at the dwarfs’ house

and indulge in some spring cleaning. Upon seeing the house

she remarks, “It’s so adorable! Just like a doll’s

house!" Again, Disney links the objectivity of women

with quaint domestic settings in which the birds sing and

the sun shines. No sooner does Snow White open the door and

step inside than she has a broom in one hand and a sponge

in the other. Walt Disney presents this cleaning spree as

instinctual, an obsession that women must fulfill; indeed,

the housekeeping calms Snow White, and she soon forgets her

dangerous romp through the forest.

In the fairy tale, however, Snow White makes an agreement

to cook and clean for the dwarfs in exchange for her room

and board. The dwarfs don’t want a vagrant, and they

know a bargain when they see one; they’re smart and

intelligent, not the comic sidekicks that exist in the film

version for eye candy and humor. In Disney’s Snow

White and the Seven Dwarfs, Snow White chooses to cook and clean;

it is in her nature, and she cannot suppress this desire.

Also, in the film version the dwarfs are symbolic of children,

and Snow White becomes the mother figure able to unleash

her maternal instincts, as seen when she refers to them as “seven

untidy children."

Though still in the dark forest, stranded far away from home,

she can now cope with her trauma because she is once again

immersed in a domestic environment. She is safe inside a

house performing motherly duties. Her kissing the dwarfs

on their way to work echoes the dutiful and obedient mother

who kisses her children before they head off to school in

the morning. This motherly attitude stems partly from Disney’s

naming of the seven dwarfs. In the fairy tale they remain

nameless, but in the film version they possess such creative

names as Sleepy and Sneezy. Bruno Bettelheim argues against

this textual change: “Giving each dwarf a separate

name and a distinctive personality seriously interferes with

the unconscious understanding that they symbolize an immature

pre-individual form of existence which Snow White must transcend.

Such ill-considered additions to fairy tales, which seemingly

increase the human interest, actually are apt to destroy

it because they make it difficult to grasp the story’s

deeper meaning correctly."

By presenting the dwarfs as children who cannot take care

of themselves, Disney emphasizes the film’s issue of

domesticity and implies that, for women, submissiveness and

menial chores are an inescapable part of their lives. In

the film version, the dwarfs become clowns whose constant

care hinders Snow White’s blossoming intellect and

ability to think for herself. By creating seven dwarfs who

are fun, lovable, and extremely child-like, Disney suggests

that they provide a happy and safe alternative to the gothic

woods, thus reinforcing the message that women should remain

home with their children and tend house.

In the fairy tale, however, the dwarfs continually chide

Snow White for falling prey to the queen’s plots. They

warn her of impending danger, and they must constantly save

her from death. They understand she is a child, and they

attempt to supply the necessary adult supervision that will

allow her to make intelligent decisions and mature. In the

fairy tale, they do not exist as mere comic relief. Rather,

they act as moral and intellectual guides, trying to help

Snow White develop so she can escape the fate that ultimately

awaits her.

In contrast to the Grimm’s fairy tale, Disney implies

that the need for independence and autonomy stalks women

continuously, as illustrated when the wicked queen, herself

symbolic of the gothic, discovers Snow White is alive and

plots her murder. That the queen poisons a gorgeous red apple

is reminiscent of the Garden of Eden. Just as Eve was tempted

by the tantalizing fruit, so is Snow White entranced by the

luscious apple. The apple represents nature, the serenity

and tranquility that often accompany domestic bliss. Or at

least Snow White believes it does; with its gothic spell,

the apple also seems to represent the sexuality of adolescence,

which, according to the film, is exactly what Snow White

should not possess. She is so innocent, however, that she

does not recognize her need for such maturity. Because Snow

White is associated with nature, though, the queen knows

Snow White will find the apple difficult to resist. The apple,

however, has been steeped in Gothicism, and Disney illustrates

this when the queen casts her magic spell and a skeletal

image covers the apple. Thus, it is not the apple itself,

but rather the gothic spell encasing the apple, that places

Snow White in her deathlike trance.

Clearly, the queen wishes to lure Snow White away from her

domestic environment, one without which the young girl cannot

survive. Although we cannot fault Snow White for falling

prey to the lure of the apple, we can fault the girl for

not sensing danger when the old beggar women, a grotesque

woman with warts and stringy hair, appears at the window

and interrupts Snow White’s daily chores. The hag’s

arrival in the forest is as strange and out of place as a

leper competing in a fashion show. Clearly, this is an example

of the gothic invading the domestic household, yet Snow White

does not realize it because she has never been given the

opportunity to develop those rational thinking skills that

might have allowed her to make those crucial connections.

The scene’s climax, in which Snow White bites into

the apple and collapses on the floor, seems to warn women

that such independence can kill their lifestyle; Disney implies

that women should be careful who they trust, lest they be

corrupted by the need to break away from the nuclear family.

At the end of the fairy tale, the queen attends Snow White’s

wedding and dies at the celebration when she’s forced

to don a pair of hot iron shoes and dance. Certainly, such

an ending is gruesome, but it is also well deserved and enhances

the moral that evil acts breed evil consequences. The film

version kills the queen by having her fall off a cliff in

the middle of a raging thunderstorm. This gothic atmosphere,

with its claps of thunder and peals of lightning, further

enforces the idea that women should steer clear of independence.

The queen herself is killed when lightning shatters the cliff.

She plummets to her death, only to be crushed by a massive

boulder. Here, Disney shows that Gothicism, hence freedom

and self-determination, is deadly to all women.

Yet the viewer may wonder why such a death even occurs if

the queen herself symbolizes the gothic. We can only assume

that by leaving her own safe environment, albeit a dark and

gloomy one, the queen places herself at the mercy of those

very same forces that drive Snow White through the forest

and deliver her into the dwarfs’ house. Just as Snow

White should have remained alone in the household, so should

the queen have remained alone in her gothic castle. The death

of the queen could also indicate the defeat of the “dangerous" freedom

that the gothic symbolizes. In either case, however, the

scene conveys that not only should women remain in their

comfort zones, but also that women should be mindful of each

other, as there clearly exists a battle for domestic space

and masculine attention.

To further the love story, Walt Disney has Snow White awaken

when the Prince kisses her, whereas in the story she awakens

when her glass coffin is moved and the apple falls from her

lips. This change in the story emphasizes the film’s

domesticity by suggesting that a woman can only be saved

by a man, thus implying that men have power over women. Disney

again stresses this idea at the end of the film when Prince

Charming places Snow White on his horse and leads her away.

He does not ride on the horse with her, rather he leads both

her and the horse, thus accentuating the idea that, like

the horse, Snow White is now merely a piece of property.

As a result, the viewer perceives her as more of an object

than as an individual woman, a doll to be shut in a glass

case and constantly admired.

I can empathize with Snow White. I understand her need for

compulsive cleaning, the obsession that drives her to organize

her life, and the overwhelming desire to wish for a future

bursting with bright lights and never-ending smiles. But

I also understand that her plight is gender-based, as well

as psychological. It’s taken me years to realize that

Snow White doesn’t have a choice. She might be obsessive,

and she might be compulsive, but she doesn’t know why.

The gothic beckons to her, waiting in the shadows with a

pencil and a notepad to offer her some much-needed therapy;

it wants to help guide her toward some semblance of freedom

and independence. In his film Snow White and the Seven

Dwarfs,

Walt Disney molds the gothic, much like the female gender,

into socially acceptable stigmas that clearly delineate a

woman’s place in society, and then he illustrates the

dangers inherent in trying to break free from those boundaries.

Although Snow White cannot be saved, her animated plight

has taught me that an obsessive desire for order may not

always produce happiness, nor may the days flow by effortlessly

as though adhering to a written text.

Sometimes it is best to wander into the woods.

March 2007

From guest contributor Michael Howarth

|