When a professional league for American football finally started up in 1920, the only day available for games was, inconveniently, the Sabbath. Colleges had long ago appropriated Saturdays, and Friday nights belonged to high schools. Even a full century later, when the NFL dominates our country like no other sport, some Christians still reject the playing and watching of Sunday football as desecration of the Lord's Day. Not only does it constitute an idolatrous distraction from piety, it encourages an abundance of sinful behaviors – including spectators' drinking, gambling, and lustful appreciation of cheerleaders, and the vanity, wrath, and violence exhibited by players held up as heroes.

Back in the NFL's early years, condemnation by Christians posed a much greater threat to its prosperity than seems imaginable now. The history of NFL-Christian relations might have played out in a number of different ways. As many Christians nowadays like to tell the story, involvement with the NFL offers them a platform for modeling virtues and disseminating their beliefs. Christianity uses the NFL, in other words, for promoting something much more important than sports. But the truth is something much closer to the reverse of this formulation: it is the NFL that uses Christianity, not the other way around. As it evolved from a struggling, marginal enterprise into today's cultural behemoth, the NFL domesticated Christianity. It contained and tamed Christian interests in order to enhance its success without ever betraying this secret inversion of secular and religious priorities.

A turning point in this history can be pinpointed as the year 1960 when Pete Rozelle became NFL commissioner. At the time, the league had nothing remotely approaching its current popularity. The twelve teams played in stadiums only partly full, and most games were not shown on television. (Some teams, like the Los Angeles Rams of my youth, had local contracts for the broadcast of away games.) Only a small fraction of Americans identified the NFL as their favorite professional sports league. Over the next few years, Rozelle would take a number of steps to address the NFL’s structural weaknesses. One thing he could do nothing about, of course, was the matter of Sunday games. And influential Christians with traditional ideas about the Sabbath had registered their objections quite clearly through the 1950s.

For one thing, some talented players refused to join the league because of their religious convictions. Probably the most prominent player to do so was Donn Moomaw who starred as linebacker on an excellent UCLA team coached by Red Sanders. A two-time All American, he was bigger than most linebackers of that era (6'4", 228 lbs), and had exemplary range and toughness. In 1953, the Rams selected him with their first-round draft pick. "All my life I wanted to play for the Rams," recalled Moomaw many years later. "It was beautiful to be drafted by the hometown team. But, as a young man, I had to deal with some very heavy things about my vocational life." He agonized over the decision, but at the last moment he turned down the chance to play for the Rams. He did not object to playing football for a profession, to be clear: in fact, he signed and played with a team in the Canadian Football League, which had no Sunday games. Moomaw went on to become a Presbyterian minister – pastor to Ronald Reagan, among other things – and said he never regretted his decision to choose Sabbath observance over the NFL. His decision influenced another UCLA star from the 1950s, Bob Davenport, to decline an offer after he was drafted by the Cleveland Browns.

At the same time Moomaw renounced Sunday football, Billy Graham, probably the most important Christian voice in America, was expressing similar views. Through the 1950s, Graham held to the orthodox position about keeping Sunday safe from inappropriate secular distractions. He agreed with the view of evangelist Howard Williams who had offered this comment about one of the early professional football games in the 1920s: "There will not be a single Christian [in attendance]," Williams remarked. "Probably, however, hundreds of church members will be there." In fact, it wasn't until 1933 that all the states adopted legislation to make football even legal on Sundays. Graham in the 1950s counseled his followers against abusing the Sabbath by attending football games, legal or no. And as late as 1960, the year Rozelle took over the NFL, Christianity Today published an editorial strongly criticizing Christian athletes who played professional football and thereby "yielded to the lure of money and added fame, and joined in the desecration of the Lord's Day."

But as the NFL grew in cultural stature – and subtly evolved in its relationship with Christianity – Billy Graham found himself in a difficult position. He did not abandon his earlier ideas about the Sabbath, but he was enough of a pragmatist to realize that the NFL had woven itself into the fabric of American Sundays. By the middle of the 1960s, with the NFL surging in popularity, Graham conceded that individual consciences might reach different conclusions about whether playing and watching Sunday football was sinful. He wrote a piece for Reader's Digest in 1974 in which he acknowledged, with regret, the new consensus: "What Ever Happened to the Old-Fashioned Sabbath?"

Rozelle's single most artful maneuver as he positioned the NFL to sanctify Sunday football came in 1973 when he founded NFL Charities. The league's teams collectively donated money to support a number of philanthropic organizations; individual players were encouraged to start their own philanthropies. All of these efforts were well advertised during games. Christians watching football on the Sabbath, in other words, had at least some reason to feel good about themselves for their support of the NFL. Interspersed among commercials for beer and trucks, announcements came of noble causes to which football was committed. Pope John II, who worried that contemporary Sabbaths had increasingly been given over to shallow and morally suspect entertainments, believed that charity was an essential outcome of genuine observance. In the apostolic letter Dies Domini, he particularly emphasized this point: "From the Sunday Mass there flows a tide of charity destined to spread into the whole life of the faithful." NFL Charities provided a convenient link between the dubious Sabbath focus on gladiatorial violence and the charity Christians regard as their greatest virtue.

The NFL's charity was not pristinely generous and selfless in the way it might have seemed. The money for charity was funneled from the profits of NFL Properties, an earlier Rozelle innovation (1963). With NFL Properties, Rozelle established centralized and very strict licensing control over team-related merchandise. He first got the idea in the late 1950s, when he was general manager of the Rams. The Rams made a little money from glassware and other souvenir items under his marketing scheme. As commissioner, he took the idea league-wide. In the early years, the profits were modest – the league was just beginning to catch on – but Rozelle saw an opportunity to use this extra money to serve another purpose: the improvement of Sunday football's image. To summarize, then, Rozelle first made a canny business move that produced a little additional profit; then, as a secondary strategy, he directed those profits into charities as a public relations gesture. Charity flowed only as an outgrowth of, and remained dependent on, the primary NFL business enterprise. Rozelle's instincts were superbly on target both in licensing and in philanthropy. Profits from NFL Properties have grown exponentially over the decades, and the NFL has needed every bit of public relations credit, and religious support, to weather troubles involving player behavior and mounting evidence of brain injury.

The NFL's successful domestication of Christianity can best be appreciated through analysis of a few tests of their relationship. In one case, the communal spirit of a church found itself in conflict with the business interests of the NFL over territorial rights to Super Bowl Sunday. In another potential conflict of interests, involving Tim Tebow among other players, the NFL used regulations to prohibit Christian messages in certain forms. And the emergence of player-led prayer huddles triggered an interesting process of give-and-take between football's governance and Christian voices within the league.

John Newland, pastor at Fall Creek Baptist in Indianapolis, organized a big church event for Super Bowl Sunday in 2007. Like many other Christian leaders, he had come to accept the NFL as an integral part of the modern American Sabbath. Indeed, on the Sunday of the Super Bowl, football took such prominence that it had become an unofficial national holiday. Newland planned to make Super Bowl Sunday as much of a Christian event as he possibly could. He invited his congregation to view the game at church on a giant screen; leading up to the event, he had solicited donations of money for food.

Much to his surprise, Newland received a cease-and-desist order from the NFL's lawyers. He was in violation of league regulations and must not proceed with his plans. There was a problem both with the size of the screen and the solicitations connected with the event. The pastor had no wish to face legal repercussions and cancelled the gathering. When word of the cease-and-desist order spread, many other churches around the country became nervous and cancelled similar events.

In an interview later, Newland explained what he had taken from the chastening. His tone indicates how effectively the NFL had tamed its Sabbath partners. It disciplined them, firmly but gently, and the pastors complied without even slightly questioning the league's authority. Newland even used football terminology in describing the experience: "The NFL flagged us because our website asked members to donate money for food for the event. They were not prohibiting us from sharing our faith; they were prohibiting us from showing their product in the way we wanted to show it." As Newland continued, he tried to frame the incident in a way that kept religious authority at the forefront: "We learned two things. One, God clarified for our country an event that churches all across the country were doing. And two, our church was challenged to be more aware of copyright law." "Copyright law" comes second, but it's really the whole point of this little brush with the NFL. The pastor saved face well enough, which is what the NFL wanted, of course. It means to domesticate Christianity, not make an enemy of it. It's telling, though, that Newland's plans for an upcoming Super Bowl include "a gospel presentation and personal testimony...at halftime." Football dominates the evening, but does not utterly overwhelm its Christian content.

A second test involved personal religious messages from players. During his college career at the University of Florida, Tim Tebow offered up Christian messages in the form of Bible verses neatly lettered onto his eye-black striping: John 3:16, Eph 2:8-10, Ezek 13:18-20, and several others. Surely he wished to continue the practice as he continued his career with the Denver Broncos. But the NFL had a rule strictly prohibiting any such messaging. The relevant article reads as follows: "Personal Messages: The league will not grant permission for any club or player to wear, display, or otherwise convey messages which relate to political activities or causes, other non-football event, causes, or campaigns, or charitable causes or campaigns." Tebow never tested the rule, but Saints' linebacker Demario Davis did. In 2019, he was seen on the sideline wearing a headband that read "Man of God," and the NFL promptly fined him $7,000.

The wording of the league regulation shows careful crafting. "Personal" is a broad enough category to include such things as religious messages, but nowhere does the NFL specify religious content – although it does specify "political activities or causes." Evidently they considered it safe enough overtly to proscribe political messaging, but they refrained from doing so with religious messaging. Christian messages are subject to the same discipline, of course, but less conspicuously. It is precisely this sort of finesse that has helped the NFL in its domestication of Christianity. And in the matter of religious messaging, their strategies have worked well so far – although at least one legal scholar believes Tebow could successfully sue the league based on Title VII of the Civil Rights Act (prohibiting employment discrimination based on religion).

At this point, a question might arise: why would the NFL feel a need to police things like the Tebow eye-black messages and the "Man of God" headband? I would suggest two reasons, both of them having to do with bottom-line business interests. One reason connects back to NFL Properties and Rozelle's licensing policies. The league saw long-term profit potential, as well as a chance for more equal division of resources, in retaining strict control over use of the NFL brand. Teams and players are not allowed to freelance with uniform items and other paraphernalia that deviates from centralized marketing. This prohibition includes all messages indicating affiliations with companies, organizations, and causes not officially licensed by the league. The other reason also reflects the pragmatic business interests of the NFL although they are better disguised as a manifestation of American religious pluralism. The NFL does not wish to appear to favor Christianity above all other creeds. They maximize their profits when no one declines to buy season tickets or turns off games out of irritation over players' evangelical zeal. Fans come in all religious varieties – Tebow-friendly evangelical Christians, Protestants from more mainstream churches, Catholics, Jews, non-Christian theists of many other beliefs, atheists, agnostics. League rules about personal messaging effectively protect professional football from establishing a religion, all the while keeping Christianity in tow as its quiet, domesticated Sunday partner.

In practice, the NFL has not been able to keep its Christian partner as quiet as it would prefer. The emergence of prayer huddles in 1990 posed another test for the league's ability to restrain Christian messaging. The first organized prayer huddle came at the end of a Monday night game between the Giants and 49ers. The two team chaplains had planned the event during the week and received informal permission from their general managers. Because a fight broke out between a few players at the end of the game, the plan almost came to naught; but when things calmed down, a number of Christian players from both teams huddled mid-field to pray. ABC cameras lingered to focus on the novelty. Sports writers learned of the huddle's Christian design and wrote about it. Similar huddles continued through that year's Super Bowl – won by the Giants.

The league began to see signs of a backlash against the heavy Christian presence on the field. Most telling was an opinion piece by Rick Reilly in Sports Illustrated, then widely read and influential. Right after the Super Bowl, in "Save Your Prayers, Please," Reilly complained about the prayer huddles. "I have a Jewish friend who is a big Giants fan, but these heaven huddles are getting to be too much for him," he wrote, then quoted the friend: "I come to see the game...but that doesn't mean they have a right to shove their religion down my throat." Reilly goes on to assert that "promotional prayer is wholly inappropriate to a sporting event," that he "resents religious sales pitches," and he "hopes that the NFL will have the good sense to curtail these huddles." The NFL must have taken notice. At the next owner's meeting in winter of 1991, they decided to enforce a rule that would indeed "curtail" prayer huddles: the non-fraternization clause. (Again, with characteristic finesse, the league avoided specific mention of religion as it introduced a measure to quiet religious messaging.) The non-fraternization clause ensures that players from opposing teams do not give the appearance of being overly chummy while in persona as competitors. To the point in question, players are required to leave the field promptly following the end of a game. The NFL sent out a memo to teams before the new season that they intended to get serious about the rule. Violations of non-fraternization would draw fines in the range of $25,000.

But the league would soon find out that its disciplinary power over Christianity had limits. The Giants continued their prayer huddles, and no fines came. Someone in the NFL office advised the commissioner that imposing fines on praying players would amount to a public relations disaster. So they quietly let the huddles continue without penalty. Over time, as prayer huddles became commonplace, no one seemed to notice them. In this case, the NFL clearly had to give a little in its negotiations with Christian interests, but ultimately football did not sacrifice much. The Christian ceremonies faded quickly enough into the background. And in tolerating the prayer huddles, the league retained the substantial benefit it enjoys from association with Christian discourse about character, values, and integrity – benefits it needs more than ever with incidents of domestic violence and increasing evidence of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy.

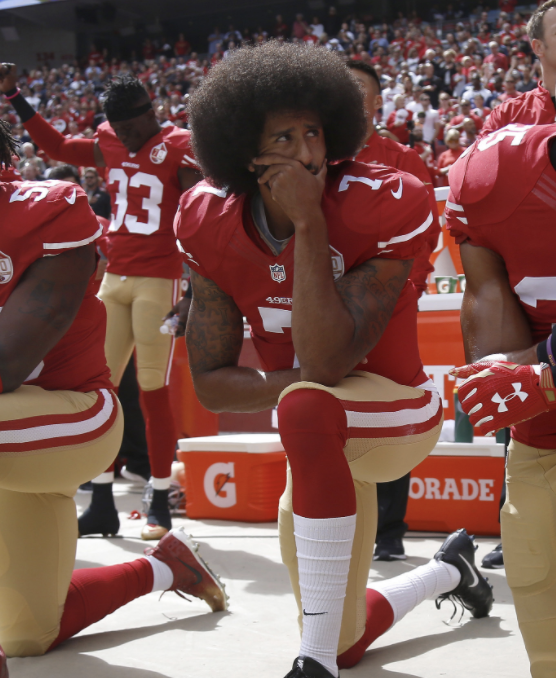

Just as I was writing these last reflections about prayer huddles, a new controversy rose up to threaten the NFL's cozy association with the Christian values it has tamed and drawn into its corporate orbit. This controversy has to do with the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police. The problem for the NFL goes back a few years, with an event that also involved kneeling players, but this time not in prayer huddles. Quarterback Colin Kaepernick of the 49ers took a knee during the national anthem to protest police violence and racial injustice. Over time, as other players joined him, Donald Trump blustered that it was an unpatriotic, despicable act, and he dared team owners to fire any kneeling players. The NFL issued a ruling that it would fine players who did not stand for the anthem – although when the players association objected, the policy was put on hold and never enforced. Kaepernick, however, lost his job, and never found another one in the league, despite the fact that he had led a team to the Super Bowl. Kaepernick believed that the teams had conspired not to sign him; he sued, and the NFL agreed to a settlement (for unspecified damages) before the case could come to trial.

In the aftermath of the George Floyd killing, many people recognized what looks like hypocrisy on the part of the NFL. The most striking expression of this sentiment came from Sally Jenkins of the Washington Post, in "This Is Why Colin Kaepernick Took a Knee": "Two knees. One protesting in the grass, one pressing on the back of a man's neck. Choose. You have to choose which knee you will defend. NFL owners chose the knee on the neck." Jenkins concludes her essay by lamenting that the NFL "might have been examples of true, righteous Americanism, [but] they chose the wrong knee." In using the word "righteous," she tacitly acknowledges the moral underpinnings of the image that the league tries so carefully to curate.

Commissioner Roger Goodell issued a statement in which he drew on the league's association with philanthropy and Christian values to announce their ongoing commitment to improve communities. "We recognize the power of our platform.... We embrace that responsibility." Sports writer Michael Shawn-Dugar tweeted in response, "Colin Kaepernick asked the NFL to care about the lives of black people and they banned him from their platform." Texans' wide receiver Kenny Stills put it more succinctly: "Save the bull----." Several teams released statement similar to Goodell's. Some, like the one from Falcons’ owner Arthur Blank, emphasized the importance of peaceful protest. "Peaceful protests of the past have led to new ways forward," he wrote. "Any form of violence has never been productive and is not the answer." Kareem Abdul-Jabbar had an answer ready: "[Kaepernick's] protest was a peaceful protest about this very issue. And he was ostracized, he lost his job, and he was blackballed for it. That's what it got you. And nothing has changed since then."

Blank was one of 32 owners who blackballed the peaceful protestor who now – in light of the George Floyd killing and its aftermath – looks more and more like a hero Christians ought to admire. Evidence for blackballing is clear enough. Former NFL executive Joe Lockhart, at the time Vice President for communications and governmental affairs, wrote a recent essay apologizing for his role in the Kaepernick affair. "I was wrong," he admitted. "I think the teams were wrong for not signing him." He explained that the commissioner as well as some coaches pushed for signing Kaepernick, but the owners balked, even though "football insiders were clear he had more talent than many of the backups in the league." For the owners, however, business interests trumped all other concerns. According to Lockhart, "One team that considered signing Kaepernick told me the team projected losing 20% of their season ticket holders.... No owner was willing to put the business at risk over this issue."

With the George Floyd protests and their connections to Colin Kaepernick, the inversion of secular and religious priorities that the NFL prefers to keep secret has become exposed as never before. Those Christians who have been struggling anyway with the idea of Sabbath football may find it harder now to justify their continuing participation. A good example of such a person might be Eric Miller, Professor of History at Geneva College. In 2007, Miller published "Why We Love Football: Grace and Idolatry Run a Crossing Pattern in the New American Pastime," a thoughtful essay in Christianity Today expressing complicated feelings about his attachment to the Pittsburgh Steelers. On the one hand, he acknowledges the worldly motives of the league, and the way it has come to dominate Americans' Sunday lives: "We've become playthings of profiteers." But he wants to believe that football also offers "a pathway to that which matters...perhaps even to a noble ethic." In his wish to continue watching the sport he loves, he was willing to believe that the NFL's Christian-inflected nobility mattered more than its selfish secular motives. I wonder: can he still believe in that nobility? Or might he now be inclined to join with Kenny Stills: "Save the bull---?"

From guest contributor Wayne Glausser, DePauw University

September 2020

|