In what is sometimes called its Pioneer Myth, California

has always seemed the ideal venue for the American dream.

Even today, loading up a Ryder truck and moving to The Golden

State is less about displacement than adventure. At the same

time, the subtitle to a 1989 cover story on California for

Newsweek voices the state's siren song: "American

Dream, American Nightmare."

Appreciating this paradox means beginning, at least, with

the last part of the nineteenth century. An 1880 poster promoted:

California

The Cornucopia of the World

Room for Millions of Immigrants

43.795.000. Acres of Government Lands Untaken

Railroad & Private Land For a Million Farmers

A Climate for Health & Wealth without Cyclones or Blizzards.

Such was the promise for individuals who were willing to work

hard for their fortunes, embrace the bountiful frontier, and

actively shape their society. Their state's destiny seemed

wide-open: in his insightful study, Americans and the

California Dream (1973), Kevin Starr writes of the last

half of the nineteenth century, "At its most compelling,

California could be a moral premise, a prescription for what

America could and should be." Less compelling were the

state's Gilded Age monopolistic businesses, corrupt politics,

and racist institutions (particularly against Chinese immigrants).

The result was the state's "divided fable," as Starr

calls it, split "because California's experience had

been a rhythm of expectation and disappointment, ideality

and harsh fact." California, in other words, was, and

is, extraordinary yet unexceptional, a virtual magnet for

those seeking to reconstruct themselves and the American dream.

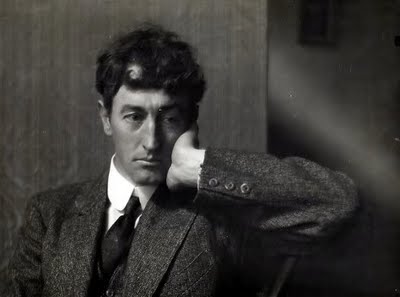

At the turn of the twentieth century, George Sterling (1869-1926)

exemplified California's divided fable. Sterling, a Decadent

poet who today is largely forgotten, was once seemingly secure

in the American literary canon: Mary Austin wrote in a 1927

American Mercury article that, if Sterling's position

would be "not the highest, it will surely be not a low

one." Austin was too optimistic. By 1929, Alfred Kreymborg,

although an admirer of Sterling's sonnets, would write that,

in the case of Sterling's "A Wine of Wizardry" (1908),

"The wizardry was borrowed, and the amazing rhetoric

almost devoid of life and human contact." More recently,

critics have generally dismissed Sterling's art altogether,

resigning, as Joseph W. Slade says in his 1968 article for

The Markham Review, that Sterling "is remembered

chiefly for his literary associations." To be remembered

lowly, though, is at least not to be forgotten.

Despite his fallen literary status, Sterling’s career

is worth studying, for his example suggests the categorical

limits to what may be construed as the three principles of

life: vocation, location, and society — what we do,

where we live, and with whom we associate. This seemingly

simple formulation is complicated by the ways in which principles

overlap or split: we want to “have it all," but

we might love our region while disliking our work, or we might

love our families but dislike our colleagues. Although compromise

becomes necessary, the very opportunity to maximize any or

the sum of these principles emerges as a working definition

for the American dream. Identifying these three principles,

in fact, is the point here, not a thoroughgoing explication

of a man's entire life and career.

1. Vocation: From Enthusiasm to Pedantry

Vocation is central to the American dream, and California's

forty-niner promise "to get rich quick" continues

to exemplify America's seemingly wide-open opportunities.

Silicon Valley's "dot-commers" are the Pioneer's

descendents. In the category of vocation, at one limit is

what may be labeled enthusiasm (literally, "having a

god within") and at the other pedantry. Neither limit

is logically possible: because we do not live in a vacuum,

we organize institutions, but in the very act of organizing

are the seeds of pedantry. To moderate between the extremes,

we typically strike a balance in the principle of service,

a principle most obviously manifest in our everyday jobs.

The business of America is business — and nowhere is

that more apparent than in California.

In 1890, Sterling moved from Sag Harbor, New York, to Oakland

in order to work for his uncle, Frank C. Havens, in Havens'

real estate ventures. However, except for meeting his future

wife, Caroline ("Carrie") Rand, Sterling had his

mind elsewhere. In his 1964 biography of Jack London, Richard

O'Connor depicts, "The best George could do, in that

line, was show up for work punctually each morning, often

with a colossal hangover.... [For Sterling] would never be

anything more than a timeserver in business." Timeserving

soon gave way to frustration. While scribbling checks for

Havens, Sterling was asked whether poetry interfered with

his business. His response was worthy of Oscar Wilde: "No,

hang it! Business interferes with my poetry." What followed

in Sterling's career alerts us to the danger in such all-or-nothing

logic.

In Sterling's enthusiastic eyes, the model poet was Joaquin

Miller, the bearded, self-styled "Poet of the Sierras"

and vestige of San Francisco's literary frontier. Self-styling,

though, is not enthusiasm, and Miller was only too conscious

of this distinction. Even as early as the 1870s, Miller defended

his wearing outrageous western garb while visiting England:

"It helps sell the poems, boys!" At first, Sterling

missed the point, imitating Miller's illusion by favoring

personal appearance over artistic production. Rarely did he

take the time to revise his work. Sterling's pedantry surfaced

in smaller ways: Albert Parry wryly notes in Garrets and

Pretenders (1933) that Sterling loved the very word “Bohemia,”

rhyming it "with anything but anemia." In the end,

though, Sterling gave up on Miller, eventually noting that

Miller "wrote with a quill, a very stub affair, which

made the interpretation no less difficult. And I grieve to

state that this illegibility was but another of his poses.”

Spun between the vocational poles of enthusiasm and pedantry,

Sterling grew to resent the necessity of having a vocation

at all. The result was a double standard, Sterling disparaging

the wealthy even as he fed on their surplus. In his play written

for the summer retreat of San Francisco's elite Bohemian Club,

The Triumph of Bohemia (1907), Sterling has the Spirit

of Bohemia destroy Mammon, Bohemia arguing that Mammon cannot

buy "A Happy heart!" The Club itself, though, was

by then constituted of well-heeled businessmen, and Sterling

never stopped brooding about this contradiction. His short

poem, "In the Marketplace," concludes:

In Babylon, dark Babylon,

Who take the wage of shame?

The scribe and singer, one by one,

That toil for gold and fame.

They grovel to their masters' mood;

The blood upon the pen

Assigns their souls to servitude —

Yea! and the souls of men!

In writing these lines, Sterling knew, apparently, how far

he was from his original enthusiasm.

Much of Sterling's poetry reflects his increasing pedantry.

Propelling his muse was a different vestige of California's

literary frontier, the west coast's leading literary arbiter,

Ambrose Bierce. Bierce, a craftsman of language, introduced

his pupil to the three principal sonnet types that soon became

Sterling's favorite forms and to that wellspring of prolixity,

Roget's Thesaurus. More directly, Bierce helped edit

Sterling's works and, so, could steer his disciple toward

an art-for-art's-sake sensibility. As an example of Bierce's

inflexibility, Sterling asked in his drafting The Testimony

of the Suns (1903) whether Bierce preferred the phrase

"bubble-eden" to "heaven of rapture."

Bierce sniffed, "I like 'Eden,' but not 'bubble.' It

has hardly dignity enough." When "dignity"

imposes on enthusiasm, pedantry is not far behind.

Interestingly, Sterling clearly knew that Bierce's was the

wrong direction. After the publication of The Testimony

of the Suns, Sterling hedged in an interview with the

San Francisco Examiner’s Ashton Stevens that

"it would be rather late in the day for me to question

his [Bierce's] judgment as a critic.” In truth, Sterling

could never completely abide Bierce's aesthetics, experimenting

instead with forms ranging from attempting popular poetry

in Beyond the Breakers (1914) to imitating his neighbor

Robinson Jeffers in Strange Waters (1924). By 1925,

Sterling was disappointed in himself: he resigned in an essay

about Bierce pointedly titled "The Shadow Maker,"

"In view of the modern movement in poetry, he [Bierce]

was not, perhaps the best master I could have known."

One example of Sterling's poetry will serve to demonstrate

the product of his vocation. Only on Bierce's insistence,

"A Wine of Wizardry" (1907) appeared in the pages

of Hearst's Cosmopolitan. Even the poem's physical

publication slogged in its own pedantry: separated from the

magazine's other pages on thicker paper and framed by luxuriant

decorations by F. I. Bennett, the effect was heightened by

the editors' headnote announcing that the poem served to rebut

the British author James Bryce's disdain for American poets.

In a supplementary essay, Bierce trumpeted, "I hold that

not in a lifetime has our literature had any new thing of

equal length containing so much poetry and so little else."

Contrary to Bierce’s nod, Sterling's readers wanted

something more than "so little else."

Besides its physical publication, the poetry of "A Wine"

reflects Sterling's sense of vocation. The poem, which follows

the empress Fancy's journey, finally describes the night,

a time of cessation but not of rest:

O'er onyx waters stilled by gorgeous oils That toward the

twilight reach emblazoned coils. And I, albeit Merlin-sage

hath said, "A Vyper lurketh in ye wine-cuppe redde,"

Gaze pensively upon the way she went, Drink at her font, and

smile as one content.

Fancy's inability to find fulfillment and the poet's inability

to communicate with Fancy illustrate Sterling's Decadent view

of art. Language, the medium of poetry, is inextricably tied

to society, but the beauty in which Sterling tried to believe

was completely apart from any human reference. Vexed by this

paradox, as George Douglas has noted, Sterling came to identify

with rejected poets: "I know how they feel…. They

know how far short they fall of what they want to say.”

The critical response to "A Wine" was predictably

far less generous than Bierce's. Porter Garnett wrote in a

Pacific Monthly review that Sterling's effort was

"bad art," "The sensation derived from reading

it…not unlike the sensation that might be caused by

listening to the hammering of a tattoo on a sweet-toned bell.

The sensorium is set in vibration, but it cannot vibrate truly."

It could not "vibrate truly," no doubt, because

Sterling himself seemed uncertain what he was trying to accomplish.

In a letter to Upton Sinclair of June 7, 1924, Sterling waffled,

"If you can make out…where I stand as to 'art for

art's sake' you'll be lucky. It seems to me I've no bone-bound

convictions on the subject, but prefer to let each man follow

his natural bent.”

Sterling's vocational crisis was visibly exposed when, in

1914, he was divorced from Carrie and ventured east to test

himself apart from his California status. Sterling's efforts

were commercially fruitless and personally humiliating, and

he found himself lonely for his friends, removed from public

tastes, and reduced to accepting charity. In 1915, he retreated

to San Francisco, where, despite his shortcomings as a poet,

he still had his status. To his (and our) astonishment, Sterling

found some lines of his poems carved next to those of Shakespeare,

Dante, and Goethe in the Gate of the Four Seasons for the

Panama-Pacific International Exposition. The moment dramatized

how quickly enthusiasm can shift to pedantry. Dwarfed by the

Exposition's concrete structures that were themselves imitations,

Sterling read an ode celebrating the occasion but then overstepped

in proclaiming himself "Poet Laureate of San Francisco."

Harriet Monroe followed with a scathing review of Sterling's

poetry for the March 1916 issue of Poetry, dismissing

it as so much "tinsel and fustian, the frippery of a

bygone fashion." Although not amused by Monroe's comments,

Sterling also winced at their truth. In a letter to John Myers

O'Hare of March 12, 1916, Sterling could only joke, "The

funny thing is that the old girl is probably correct! Peace

to her undemanded maidenhead!"

Despite his manifest poetic failings, Sterling's lifetime

of clear prose letters and commentary hints at what he might

have accomplished in poetry had he pursued a more moderate

vocational track. In 1929, B. Virginia Lee estimated in

Famous Lives, "Perhaps the pithiest of all Sterling

legend is forever buried in his personal letters. Here he

was free to damn or bless; either of which he could do to

the king's taste.… They were rich in wisdom and health."

Such letters numbered about one hundred a week, and, on certain

occasions, the honesty of his prose even inspired his poetry.

Notably, before his suicide in 1926 Sterling scrawled a final

poem titled "My Swan Song":

Has man the right

To die and disappear

When he has lost the fight?

To sever without fear

The irksome bonds of life,

When he is tired of strife?

May he not seek, if it seems best,

Relief from Grief? May he not rest

From labors vain, from hopeless task:

— I do not know; I merely ask.

We can only imagine Sterling gazing at himself in the mirror

while writing these lines, his classical profile by then so

eroded that he appeared, as it was expressed by those like

Charmian London, "A Greek coin run over by a Roman chariot."

However, the limit of anything is not about moderation, and

Sterling dismissed the poem as "crude stuff.” Others

who followed would provide the corrective: whether the likes

of John Steinbeck or, later, Remi A. Nadeau (in such works

as The Water Seekers and California: The New

Society, most of California's writers know that the state's

golden promise is far from free and certainly not easy.

2. Location: From Preservation to Exploitation

Like those for vocation, terms for identifying the logical

limits to location vary, but at one end is what may be called

preservation, in which location is deemed inviolable. The

problem, however, with preservation is that it precludes our

actual inhabitation and commerce, a fact that has doomed one

utopian venture after another. Utopia, by definition, is no

place; like Thoreau, we must return to the village to earn

a living. In doing so, we in some measure move to the opposite

end of the category, exploitation. Not wishing to destroy

location, however, we typically balance preservation and exploitation

in the principle of management. Indeed, a great deal of California's

cultural history is tied to this very issue.

Between 1905 and 1914, Sterling served as the guiding spirit

for a colony of artists at Carmel, a setting of rustic retreat

that could not have been much prettier. He was close to San

Francisco and yet removed from its pace and pressures. If

anywhere, Carmel was a place worthy of careful management;

even so, the colony's founding principle was not to manage

the region but to chase real estate profit. Formed by James

Franklin Devendorf and Frank H. Powers, the Carmel Development

Company did not originally have Bohemianism in mind at all:

in its 1904 promotional brochure for the area, the company

listed the coming railroad, electric wiring, moderate climate,

potential for growth, hunting, and fishing. Only in subsequent

promotions did the company tap Bohemianism. Thus, when the

artists arrived, recounts Michael Orth in his 1969 essay for

The California Historical Society Quarterly, "There

were over seventy-five people, several stores, a restaurant

or two, and a school and hotel — not exactly a town

perhaps, but civilized enough." For his part, Sterling

was happy to assume residence on the financial wings of his

benefactor, and Uncle Havens was happy to rid himself of a

dime's worth of trouble.

In retreating from vocational pressures, Sterling and the

colonists spent a great deal of time tenderizing the local

abalone, singing a song that suggests more about them than

they probably realized:

Oh! Some folks boast of quail on toast

Because they think it's tony

But I'm content to owe my rent

And live on Abalone.

While living in this artificial paradise where no landlord

comes to collect overdue rent, the colony produced all too

little of enduring artistic merit. Meanwhile, Sterling was

downright assiduous in hunting for the colony's food, an activity

he labeled in a 1913 letter John Myers as his "best recreation."

His aim, it turns out, was far from re-creating anything.

As we may expect of a poet — especially in the Greek

sense of maker — Sterling envisioned the hunter as integral

to nature's processes. Sterling’s "Autumn in Carmel"

is nothing short of pastoral:

Hunters wait on the hillside, watching the plowman pass

And the red hawk's shadow gliding over the new-born grass.

Purple and white the sea-gulls swarm at the river-mouth.

Pearl of mutable heavens towers upon the south.

Sterling's Carmel diaries bear witness to a different muse.

On August 30, 1907, Sterling records, "There was a leopard-seal

at the 'landing,' shot this morning (w/ buck-shot). A handsome

seal. His blood smells very fishy." Sterling neither

mentions why he killed the seal nor what he did with it —

the killing was apparently its own reward for him, and years

of conscientiously recorded slaughter follow. What he ate,

he often ate uncooked: in a 1912 letter to Witter Bynner,

Sterling prescribes, "Don't fail to eat one of our mallards,

RARE.” Part of this record involves his kill ratios:

on October 15, 1909, Sterling "Got five squirrels, 6

blackbirds (1 shot), & three small ducks, (one shot)";

on October 19, he "got two small ducks, two snipe, one

lark, three squirrels, six killdee[r]s and eight blackbirds

(one shot)." Such attention tended to the callous: on

November 3, Sterling is unfunny in noting, "went hunting...&

got a loon (who's looney now?)." On October 20, 1911,

Sterling changes verbs: "Went gunning with Doc Gates

and got a quail, killdee[r] and six larks." By February

9, 1912, matters turn downright strange: Sterling writes,

"Went to the river-mouth with John Kenneth Turner in

the afternoon, to try to shoot salmon. Got no chance, but

shot a rabbit and seven larks." On April 5, 1912, Sterling

scoffs that the local game-warden asks about his shooting

sea gulls — note "Autumn in Carmel" —

yet on March 27, 1913, Sterling records that he and his company

"went to Mission Point and river mouth. Tried the rifle

on golf signs and sea-gulls." In all, Sterling's hunting

became almost random. On August 16, 1913, he "shot at

a big skunk"; on September 8 of the same year, he hunts,

along the way, "a white hawk, an owl and a pirate cat";

on October 22, he frets that his tally does not equal that

of his friend Turner.

Not surprisingly, Sterling's poetry provides a kind of commentary

on his slaughter of wild animals. Adverse response raises

the critical problem of intentionality: Sterling was a Decadent,

after all, a sensibility that favored flourish over narrative,

emotions over substance. As such, his poetry is not accountable

to contemporary tastes. Nonetheless, it is peculiar that Sterling's

nature poetry drifts so far from a sense of either preservation

or even management. For instance, although the publication

of a poem like "Yosemite" (1915) was accompanied

by a cover painting and interspersed with photographs of the

valley, the poem mainly demonstrates Sterling's range of reference

to mythology and history, overlaid with abstractions of colors,

sizes, and shapes. Despite its title, one may say, the poem

only exploits the name of the actual valley that John Muir

promoted; in fact, Sterling wrote the poem in order to pay

debts to John D. Phelan, who staked Sterling while the poet

tried the New York market. Given the circumstances, the results

were predictable:

O falling rivers, beaut[i]ful in doom!

Your lofty raiments sway

As mountain-winds fling wider to the day

The sounding fabric of a stony loom.

These lines are typical, Sterling ending no fewer than fifty-three

of the poem's 360 lines with an exclamation point. Moreover,

Sterling does not stay in this Decadent key, ultimately changing

it to promoting socialism: "O Valley waiting through

the wistful years, /The sure though distant tread/Of those

young armies of the Comrade State!"

Even Sterling was confused and bored with the effort. In

a letter to Upton Sinclair of 1924 regarding his artistic

creed, Sterling equated "Yosemite" to so much "preach[ing]."

Moderation, for Sterling, was never easy.

3. Society: From Devotion to Egoism

In the myriad possibilities for the American dream, vocation

and location are complemented by society, a principle ranging

from devotion to egoism. Like any category, though, theory

is one thing; reality is another. America proceeds, in the

famous phrase of Alex de Tocqueville, on "self-interest

rightly understood." In short, because we cannot escape

either ourselves or our social spheres, we typically sympathize

with each other, needing others as much as others need us.

For Sterling, society was the most important principle to

his California dream: In 1928, the Spring Valley Water Company

even erected a bench commemorating Sterling, inscribed with

a musical line by Uda Waldrop titled "Song of Friendship."

Despite such masonry, Sterling's friends in life were too

often passing shadows with too-easy smiles. In citing Sterling's

"In Autumn," Charmian London resigned that Sterling

"was no one's man — not even his own man. He was

forever searching into himself to be sure, but also 'lonely

for some one I shall never know'.” In the terms here,

Sterling was lonely because he could not strike a balance

between giving and taking, devotion and egoism.

At the Carmel colony, eventual inhabitants included Austin,

the young poetess Nora May French, and James Marie ("Jimmy")

Hopper. A host of visitors filtered in and out, but by far

the most important for Sterling was the very image of manly

Bohemianism, Jack London. The two met in 1901, and Sterling

soon came to call London "Wolf" after the adventurer's

Yukon experience while London called Sterling "Greek"

after the poet's classical profile. Their relationship is

best left to the record. Each failed at his first marriage

(Sterling did not remarry); each had various affairs; and

each idealized women beyond life, London seeking a "mate"

for his superman self-conception and Sterling elaborately

worshiping women like Mary Craig Kimbrough — later Upton

Sinclair's second wife. (In 1911, Sterling wrote Kimbrough

a sonnet a day for one hundred days, published in 1927 as

Sonnets to Craig.)

Most striking are Sterling's epistolary salutations to London,

for they reveal a growing deference: on May 27, 1906, Sterling

wrote to "Dearest Tiger"; on July 31, 1906, it was

"My darling Wolf"; on November 18, 1910, it was

"O Hater of Henids! O Wolf! O Mussel-trap!"; and

on January 29, 1913, it was simply "Heavenly Wolf.”

In a letter of September 12, 1907, Sterling remarked, "You,

Wolf, I love — more than I dare say." In response,

London shied from fully committing to Sterling. In a letter

of July 11, 1903, London wrote to Sterling,

And so I speculate & speculate, trying to make you out,

trying to lay hands on the inner side of you, the self side

of you — what you are to yourself in short. Sometimes

I conclude that you have a cunning & deep philosophy of

life, for yourself alone, worked out on a basis of disappointment

& disillusion. Sometimes, I say, I am firmly convinced

of this, and then it all goes glimmering, and I think that

you don't want to think, or that you have thought no more

than partly, if at all, and are living your life out blindly

and naturally.

Given the overall tenor of Sterling's letters, London's uneasiness

reflects that something had to change.

Of course, one may dismiss the relationship between Sterling

and London, to cite James Henry in his 1980 limited edition

of Sterling letters, as "Probably of great symbolic significance

to the head-shrinking clan." Suffice that the two grew

increasingly distant. While London refrained from visiting

Carmel in favor of adventure and then farming, Sterling receded

to the shadows. In a letter of October 14, 1913, Sterling

addressed London in a manner both obsequious and petulant:

"Beloved Man-with-no-time-to-visit-Carmel-but-with-two

months-to-go-cruising in! (I don't blame you)." Soon

enough, Sterling was content to provide London with scattered

story ideas, reasoning that London's more popular name would

sell better than his. Displaced to the shadows of London’s

literary light, Sterling allowed in a letter of March 30,

1913, "I know I don't deserve you, Wolf. But in a way

I am glad that I'm one of the illusions you still elect to

fall for."

His life having tested the limits of devotion and egoism,

Sterling took refuge in an anonymously donated room above

the Bohemian Club. In 1926, he spent his last, alcohol-soaked

days there, disappointed by the delayed visit of an acquaintance,

none other than H. L. Mencken. Following the suicides of Nora

May French in 1907, Bierce in 1914, and Carrie Sterling in

1918, Sterling died — alone — from cyanide of

potassium poisoning, the fatal dose from an envelope that

he had carried with him for years and marked with the word

“Peace.” Upton Sinclair responded in 1927 that

the "nebular hypothesis" overwhelmed Sterling —

that is, Sterling despaired for mankind's fate in a doomed

universe. More simply explained, Sterling was disappointed

that he could not achieve lasting social connections.

Despite his eventual suicide, Sterling could occasionally

achieve social balance. For instance, Sterling wrote a "'rough-neck'

hooch song" to London, which begins and then follows

similarly,

O the Wolf, the Wolf, the Wolf!

The fat, voracious Wolf!

He's hair on his toes,

And whiskers in his nose.

And where he gets his thirst

Christ Jesus only knows.

Sterling seemed content with the effort. In a 1921 letter

to Estelle P. Crane, he proudly observed that "Some of

the men in [the Bohemian Club]...sing it at times when tipsy."

Such might be the best of Sterling's legacy: when the club

observed the fiftieth anniversary of Sterling's death in 1976,

their Library Notes remembered their former resident as a

"living legend." No one, it would seem, can deny

that Sterling was the life of the party.

Last, in his 1957 article titled "George Sterling: Western

Phenomenon," Stanton A. Coblentz commends Sterling's

"cosmic perspective" and assesses that Sterling

was a last, rare individual in American literary history,

namely, "the full-time poet, the man for whom poetry

is both vocation and avocation." Rebuttal may be left

to a more recent British poet who could not be more different

from Sterling — Philip Larkin. In a 1979 interview,

Larkin commented, "I've always thought that a regular

job was no bad thing for a poet.... [For] you can't write

more than two hours a day and after that what do you do? Probably

get into trouble." Sterling found trouble in California's

golden promise, all right; now, in pondering his approach

to vocation, location, and society, we cannot help but reassess

our own American dreams.

June 2005

From guest contributor Peter Kratzke

|