Test screenings are standard in Hollywood

now, but they were not quite as widely employed in the mid-1980s,

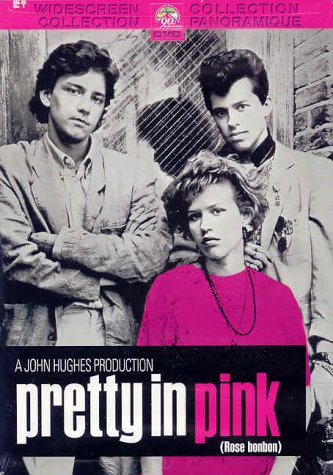

which makes all the more remarkable what happened to John

Hughes’ 1986 teen classic, Pretty in Pink. Pretty

in Pink is a fairy tale of Andie (Molly Ringwald), a girl from

the literal wrong side of the tracks, who attempts a relationship

with the wealthy Blaine (Andrew McCarthy), much to the chagrin

of her poor friend, Duckie (Jon Cryer). Succumbing to the

pressure of his rich friends, Blaine breaks his date with

Andie for the prom. As the ending was originally shot – reserved

today only in the tie-in novel, which had been pressed before

the screenings – Andie attends the prom anyway, out

of defiance. She meets Duckie outside, and they enter together.

H.B. Gilmour writes:

All activity on the dance floor stopped. . . . Andie and

Duckie stood proud in the silent ballroom, all eyes on them.

And then, finally, someone moved. The crowd parted. And Blaine

McDonough walked slowly toward them. . . . Andie took [Duckie’s]

hand and walked him out to the dance floor. The crowd separated

around them again, leaving Andie and Duckie alone at the

center of the floor. . . . Blaine thought Andie had made

this night a real graduation night for him. He watched her,

his eyes brimming with pleasure at her graceful beauty.

According to Jonathan Bernstein in Pretty in Pink: The

Golden Age of Teenage Movies, test audiences were upset

by an ending in which Andie’s

and Duckie’s “poor but honest moral superiority

gnawed deep into the corrupt souls of the richies who were

forced to deal with their own worthlessness.” Weaned

on optimistic Reagan-era perceptions of social mobility,

the audience “wanted to see the poor girl get the rich

boy of her dreams. They didn’t

care about the dignity of the oppressed.” Hughes caved

in and changed the ending, and the poor girl got the rich

boy. A year later, though, the downtrodden of the American

high school got their revenge in Hughes’ Some Kind

of Wonderful, marking a shift in attitudes toward the

rich, the poor, and the possibility of their peaceful coexistence.

In the year between Pretty in Pink and Some

Kind of Wonderful,

something made it permissible for a poor boy to choose a

poor girl and acceptable, even heroic, for people to keep

their “proper” station. This trend downward,

visible in the difference between these films but indicative

of the era’s teen cinema in general, coincided with

a burgeoning public cynicism that clouded usually positive

perceptions of upward mobility and the attainment of wealth

in America. The interplay between the cinema and the economic

landscape of the Reagan years is deepened by virtue of Reagan’s

own very personal ties to acting and show-business. Movies

had made Reagan, and his image was in turn indelibly stamped

on American cinema during his tenure in office. First in

the guise of economic conservatism and relentless optimism,

representations of class and social mobility evolved considerably

in films of this period, often mirroring the economic and

political landscape at the time. The unbridled optimism of

Wall Street during Reagan’s first years in office,

followed by problems that arose after the start of his second

term – insider-trading scandals, record-level unemployment,

Iran-Contra – find themselves reproduced in an increasingly

cynical, cinematic portrayal of class, wealth, and social

mobility toward the end of the decade. Pretty in Pink and

Some Kind of Wonderful offer a convenient focal point for

reading this national and representational rupture, a moment

that illuminates what will later be seen as the malaise of

Generation X, the pivotal point at which it became creditable

not to rise.

I. Reaganomic Optimism and the

National

Fantasy of Upward Mobility

When I was in grade school, they told me that when

I grew up I could be whatever I wanted. And I believed them. — Emilio

Estevez in Wisdom (1987)

“The people love Ronald Reagan,” wrote journalist Max

Hastings of the London Times in 1986. He went on to quote

one of his colleagues, British journalist Steve Hayward: “Reagan

understands, as our media and intellectual elite do not,

that the most prevalent feature of American character is

forward-looking optimism.” Reagan himself personified

the central tenets of the economic policy that would win

the trust of most Americans: a firm belief in the possibility

of social advancement, the inevitable reward of hard work,

and the virtuous pursuit of wealth. Reagan was his own

narrative of upward mobility, having grown up in a family

that was,

in his own words, “poor,” and his autobiography

details his rise. Reagan’s embodiment of the fairy-tale

rise prompted Lou Cannon of the Washington Post to write

that the “obligatory mythology for modern Republican

Presidents requires that they be of humble origin, preferably

born in a small town, and that they share a vision of an

America redeemed by the values of hard work and upward

striving. Ronald Wilson Reagan qualifies.” Despite

his family’s

poverty, Reagan “believed that success was there

for the taking,” and he carried with him from the

outset the optimism that would characterize his presidency.

This optimism bolstered a positive perception of wealth

from the first moments of Reagan’s inauguration on January

20, 1981, an inauguration made all the more captivating because

of political circumstances (American hostages in Iran had

been guaranteed release that very day). Haynes Johnson points

out that “never in all the previous inaugurations had

a president come to power under such intensely publicized

circumstances.” Reaganites unanimously delivered a

clear message of glitter and gold, and The Washington

Post’s extensive coverage of the inaugural weekend pointed repeatedly

to the opulence that characterized the events. Donnie Radcliffe

wrote, “The Republican aristocracy took over Washington

this weekend, making it safe again to put on diamonds and

designer gowns.” Elisabeth Bumiller added, “Forget

the Republican cloth coat. This year: mink.”

But the inauguration masked a darker national truth. One

week prior, Newsweek had proclaimed in enormous

letters on its front cover, “Economy in Crisis.” A

public opinion poll from ABC News on February 20th, one

month to

the day after Reagan’s inauguration, revealed heightened

public awareness of the dire state of the American economy.

Despite the acknowledgement that conditions were worsening,

though, the polls indicated an even firmer belief that

it would strengthen in the coming months. Responses to

other

questions on the same survey situate the attitudes of those

polled within the rubric of American class perceptions.

Fully 89% of those polled claimed familiarity with Reagan’s

proposed economic policy, which involved a series of three

tax cuts for those in higher income brackets. Respondents

overwhelmingly opined that the proposed cuts would hurt

the poor and benefit the wealthy. Despite this imbalance,

a vast

majority of 72% approved of these measures regardless

of who would be hurt. Reaganomics, if the polls

are to be believed, was embraced by a count of about three-to-one,

numbers that offer key insights into the perception of

class

and the public’s class allegiance at the outset of

Reagan’s first term.

The optimism reflected by Reagan and by the poll numbers

was initially bolstered by an actual improvement in the

nation’s

economy. Six months into his first term, Fortune magazine

contentedly reported that “after-tax incomes should

climb briskly over the period ahead – 4% a year in

real terms compared with a 1% rate in the last year and

a half.” The outlook was even stronger by the end

of 1981, and Fortune’s year-end panel of

experts on the economy, including Fed. Chairman Alan Greenspan,

prophesied

a “robust recovery.” Given the rosy path envisioned

by economists, it is no coincidence that, according to

Haynes Johnson, “the Reagan years saw the reemergence

of luxury as a national goal.” The desire to rise,

which some consider a staple characteristic of American

culture, had

an emboldened authority reflected in the films of this period.

II.

Cinematic Optimism and the Narrated Fantasy of Upward Mobility

I’ve never seen such a vulgar display of wealth in

my life! How do I get one?

— Andrew McCarthy to Rob Lowe in Class (1983)

In

her 1986 review of Pretty in Pink,

Pauline Kael makes a statement that usefully frames the

cinematic portrayal

of social mobility during the Reagan years:

In the movies of the twenties and thirties, it was common

for heroines (and heroes) to be ashamed of their poverty

and to feel a vast social gap between them and the secure

rich. But in the years after the Second World War, as

people moved up in the society, the movie fantasy of

marrying

rich lost its romantic appeal. Has this fantasy been

returning in eighties movies such as “Flashdance,” “An

Officer and a Gentleman,” “Valley Girl,” and “Pretty

in Pink” . . . ? Whatever the reason, class consciousness

has been making a comeback, but not in any kind of realistic

or political context; what we’re getting is strictly

the fantasy theme of love bridging the gap.

Outside of the marriage plot, upward mobility organizes

a multitude of other films from the 1980s: All the

Right Moves (1983), Trading

Places (1983), Risky Business (1983),

Class (1983), The Breakfast Club (1985), Brewster’s Millions (1985), Back

to School (1986), and Down and Out in Beverly

Hills (1986). In these films, questions of social mobility

are raised, but the optimism (what Kael calls “fantasy”)

proves too strong, and any real issues broached are either

blatantly ignored or thoroughly sugared over.

Studios made numerous movies for teens in the 1980s,

largely due to what Bernstein terms a sudden rise in “adolescent

spending power,” the side-effect of a general economic

boom. (The PG-13 rating, introduced in 1985, testifies

to an increase in movie-going teens at the time.) Narratives

depicting an upward rise often focus the age at which

we

make life-impacting decisions about our future, the Bildungsroman story

leached through the Horatio Alger bedrock. Bruce Robbins’ work

on what narratives of upward mobility reveal about class

relations and perceptions is particularly instructive.

Robbins’ reading

of Good Will Hunting makes the lingering presence

of Alger in the film quite clear, but his attention to

structural

specifics provides a foundation for reading social mobility

in various contexts. For example, the character identified

as “the therapist” in Good Will Hunting is

a pivotal one in that story and others. Robbins refers

elsewhere

to “mentors, counselors, benefactors, fairy godmothers,

gatekeepers, surrogate parents,” the donors adduced

by Vladimir Propp as crucial elements of folktales. Robbins

also considers larger social contexts of the upward rise

and measures the gap between fantasies of national advancement

and the harsher realities. Such narratives are important,

Robbins argues, because they disclose perceptions of

class relations and ultimately testify to the permanence

or permeability

of class.

Upward-mobility films in the early 1980s tend toward

either industrial escape or metropolitan finance. All

the Right

Moves, Flashdance, and An Officer and

a Gentleman all

emerge within this first framework and laud the movement

from

industry to middle-class comfort, or at least the prospect

of it.

In All the Right Moves, a high-school football

player (Tom Cruise) wants out of his small Pennsylvania

steel

town,

and his key to escape is a college athletic scholarship.

He explicitly

details his desire for realignment within the process

of production, from proletarian to managerial class,

from

steel-mill worker to engineer, and, though the usual

hurdles are employed,

the conclusion makes everything right. All the Right

Moves and similar films that followed it, like Flashdance and

An Officer and a Gentleman, register their disgust

with manual

labor. The films’ approbation of upward mobility

is explicit, usually in the positive reactions of those

who

remain behind. In perhaps the most gratuitous example

of this, the spontaneous applause of Debra Winger’s

co-workers in the factory, when Richard Gere walks in

and quite literally

carries her out to a better life, reassures the audience

that the rise is good.

On Wall Street, a film like Trading

Places typifies the optimistic depiction of such possibilities.

In

Trading

Places, two wealthy

brothers, the Dukes (Ralph Bellamy and Don Ameche), simultaneously

engineer the downfall of one of their brightest brokers

(Dan Aykroyd) and the rise of a homeless con-man (Eddie

Murphy),

all for a one-dollar bet. When the two victims anticipate

the scheme and exact revenge, their weapon of choice

is the stock market. Using inside information, they bankrupt

the

Dukes on the trading floor, simultaneously making millions

for themselves with capital provided by a butler (Denholm

Elliott) and a prostitute (Jamie Lee Curtis). Perhaps

most

telling is that the worst punishment the film can devise

for the Dukes is impoverishment. Trading Places was prescient

in its portrayal of insider trading, a plague that would

be exposed only later in Reagan’s presidency, but

its general fixation on finance is typical for its time.

On Ferris

Bueller’s (Matthew Broderick) day off from school,

for example, one of the few places he chooses to hang

out, right after Wrigley Field and the Sears Tower, is

the stock

exchange. The camera lingers, transfixed, on the changing

numbers, while Ferris and his friends discuss their future.

In other movies of 1986 and 1987 – e.g., Quicksilver and The

Secret of My Success – as in Hollywood

in general, the market provides the means of punishing

evil,

rewarding

good, and offering a ladder to social climbers.

Reagan-era Wall Street was dominated by flamboyant arbitrageurs

like Ivan Boesky, a bestselling author (Merger Mania)

and a vocal fan of greed. In a 1985 commencement address

at

Berkeley, Haynes Johnson reports that Boesky “was cheered as

he said, ‘Greed is alright.’” Oliver Stone’s

Wall Street (1987) considered the possibility that Boesky’s

gains were ill-gotten. Boesky was not formally charged with

insider trading until November of 1986, but it is clear that

insider trader Gordon Gekko (Michael Douglas) is modeled

on him, right down to Gekko’s speech on the virtues

of greed. Wall Street is not Gekko’s story, though,

but that of Bud Fox (Charlie Sheen), a young, upwardly-mobile

broker with working-class roots who, at one point, informs

his working-class father (Martin Sheen) that “there

is no nobility in poverty anymore.” Gekko takes Fox

under his wing and pressures him to gather illegal information.

The market is Fox’s downfall, once he is caught, but

it is also still his savior; Fox’s own network of investors

successfully defeats Gekko’s buyout of the airline

that employs Fox’s father. Wall Street still trembles

at the power of the market, but its message is slightly muddled

and its morality more complex. It is miles away from the

absolute glorification of trading in Trading Places, or even

in Quicksilver one year prior, but it clearly comes at a

conflicted time. By 1987, public opinion of Reagan and what

he represented was in flux. Faith in the almighty market

as an engine for upward mobility, and fantasies of class-permeability

in general, pervade American cinema in the early 1980s, and

John Hughes enters this dynamic when he lets the poor guy

get the rich prom queen in The Breakfast Club (1985), and

the poor girl get the rich guy in Pretty in Pink. However,

the differences between Pretty in Pink and Hughes’ next

movie, Some Kind of Wonderful, chart the starker pessimism

of the decade’s end.

III. Reality Bites

You want the truth? You want the plain truth? You’re

over.

— Eric Stoltz to rich rival in Some Kind of Wonderful (1987)

Pretty in Pink and Some

Kind of Wonderful bookend a rupture in the portrayal of class in American

cinema

of the

1980s. Pretty in Pink was released in February 1986, and Some

Kind of Wonderful opened exactly a year later. Without

insisting

on a strict equation of public mood swings and cinematic

trends, it appears that, somewhere in between these

two films, the Reagan sheen had worn thin. The economic disillusionment

that took hold became a constitutive element of the

very teenage generation that many of the movies of the 1980s – and

certainly those of John Hughes – targeted.

In May 1986, Wall Street received the first of several

blows that would change its course. According to Gordon

Henry writing

for Time, a 33-year-old mergers-and-acquisitions specialist

named Dennis Levine became the subject of “the largest

insider-trading complaint ever filed by the SEC.” Wall

Street envisioned a scandal on par with Watergate, because

investigators – and the press – publicly concluded

that, as Susan Dentzer reported in Newsweek, he “may

have plugged into a network of financial community tipsters,

possibly arbitrageurs…or other sources with access

to material nonpublic information.” Everything indicated

that the cheating was widespread, and it was Levine who ultimately

fingered Boesky that fall. The fate of the stock market during

the following year spelled disaster for public confidence

in Reagan’s economic stewardship, as it was generally

agreed that the administration had let the market run out

of control. The Dow wavered early in 1987, finally climbing

to record heights in September. The following Monday, however,

it suffered the largest single-day loss in its history, roughly

twice the drop of 1929 that had ushered in the Great Depression.

Reagan’s approval ratings of 68% at the outset of his

first term fell to 57% when the Levine scandal broke, and

they continued to slide. By mid-1987, the Iran-Contra scandal – broken

when an American cargo plane was shot down over Nicaragua

in October of 1986 – and the collapsing market had

eviscerated the president’s numbers, which ended

a full 20% lower than they were when he entered the White

House.

Polls in November 1987 equated Iran-Contra with Watergate,

the same terms Wall Street had used to describe its own

scandals.

Bernstein’s assessment of teen movies in the 1980s

contrasts the optimism of that decade with the pessimism

of its predecessor, with “the fear, paranoia, frustration

and uncertainty of America post-JFK, post-Vietnam and post-Watergate” (3).

The 1980s certainly began on an optimistic note, but

American cinema after about 1986 records a different

story.

IV.

To Rise or Not to Rise?

To be honest, trying to look like a yuppie is pretty

exhausting. I think I might even give up the whole

ruse – there’s

no payoff. I might even become a bohemian like these

three. Maybe move into a cardboard box on top of the

RCA building;

stop eating protein; work as live bait at Gator World.

Why, I might even move out here to the desert.

— Douglas Coupland, Generation

X (emphases his)

Newsweek’s David Ansen

pulls no punches in his review of Some Kind of

Wonderful.

John Hughes, he writes, “must

have written Some Kind of Wonderful so fast

he failed to notice he’d written it once before,

under the title, ‘Pretty

in Pink.’ Only the sexes have been changed.” Benjamin

DeMott, in The Imperial Middle, makes a

similar pronouncement, claiming that “the story

is the same.” In

many ways, Ansen and DeMott are correct: the number

of obvious

parallels between the two films demonstrates that

Hughes is simply cashing in on an established formula.

Both movies

feature an outcast high-schooler vying for the affections

of someone from the other side of the tracks, tracks

which are actually included in the opening shots

of both films.

The parallels in question underscore some fundamental

differences, though, and these differences ultimately

speak to a clear

shift in perspective. They begin even with the films’ soundtracks

and the role that the soundtracks play in the construction

of the narrative. The soundtrack of Pretty in

Pink,

for example, prizes wistful tunes like OMD’s “If

You Leave,” Nick

Kershaw’s “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” (“Wouldn’t

it be nice to be on your side/Even if it was for

just one day?”), and the Smiths’ “Please

Please Please Let Me Get What I Want.” The

title track – “Pretty

in Pink” by The Psychedelic Furs – thematizes

class difference, telling of a poor woman and her

wealthy lover. The soundtrack to Some Kind of

Wonderful,

by contrast,

revolves around the Rolling Stones song, “Miss

Amanda Jones,” from which the lower-class protagonist’s

love interest takes her name. The tune is ubiquitous

in the film and chronicles a wealthy girl’s

movement down the social ladder.

Some Kind of Wonderful clearly represents Amanda’s

(Lea Thompson) involvement with Keith (Eric Stoltz) as a

movement downward, and, because of this, we can categorize

her as “rich,” as Ansen and DeMott also do, even

if her social status is deliberately ambiguous. The situation

is already more complex than in Pretty in Pink; Some

Kind of Wonderful is not the fairy tale of a poor boy courting

a rich girl, but rather of a poor boy courting a similarly

poor girl doing her best to escape poverty. The wealthy Blaine

in Pretty in Pink ultimately proves himself worthy of Andie,

but Some Kind of Wonderful refuses to redeem any of its more

comfortable students. Despite her perceived status, Amanda

Jones is poor. “Do you know where she’s from?” Keith

asks, and Watts (Mary Stuart Masterson) acknowledges that

Amanda is indeed from “our sector, but she runs with

the rich and the beautiful, which is guilt by association.” The

ending of the film resolves the ambiguity by having Amanda

abandon her upward social mobility in favor of individual

strength. This final act justifies the unmediated scorn of

upward struggle embodied by Watts throughout the film. As

DeMott points out, the film’s conclusion permits both

Keith and Amanda to win, but DeMott’s reading of this

conclusion as an erasure of class misses the important point

that the only class erased is the upper one, the same class

that Pretty in Pink’s ending embraced one year

earlier. This crucial difference is, on closer examination,

reflected

in every possible point of comparison between the two

films and relentlessly troubles the notion that Pretty

in Pink and Some

Kind of Wonderful reflect similar paradigms

of social class and mobility.

If we read these two films as stories of upward mobility – as

the fairy tales whose pattern such stories follow – then

the role of the mentors or donor figures in Pretty

in Pink and Some

Kind of Wonderful becomes important. In both movies,

these enablers encapsulate the film’s overall conception

of class and its rigidity. Andie’s mentor in Pretty

in Pink is Iona (Annie Potts), the Protean manager of the

record store at which Andie works; she is Andie’s constant

friend and source of advice. The first shot of Iona shows

her in punker leather gear, her hair spiked, but she next

sports a towering beehive hairdo as she croons along with

the Association’s “Cherish.” Finally, as

she gives Andie a gown for the prom, Iona is dressed conservatively,

readying herself for a date whom she admits is a “yuppie.” This

transformation mimics Andie’s own romantic aspirations

even as it encapsulates the entire movie. Keith’s facilitator

in Some Kind of Wonderful, the skin-headed delinquent Duncan

(Elias Koteas), remains, for the duration of the movie, precisely

as we first see Iona in Pretty in Pink, clad in punker leather

and looking intimidating. After meeting him in detention,

Duncan ultimately engineers Keith’s entire date with

Amanda Jones, gaining the couple entrance into the art museum

where his father is a security guard, and having one of his

henchmen break open the gate to the Hollywood Bowl for them.

Duncan magically appears at the party of Amanda’s wealthy

ex-boyfriend, Hardy Jenns (Craig Sheffer), the film’s

climax, where he physically intervenes to help Keith and

Amanda against her rich friends’ interference. Duncan

and Iona perform similar narrative functions, but Duncan

never becomes a yuppie. His presence in Some

Kind of Wonderful is a constant nod to the high school’s disgruntled

untouchables.

The final showdown in Some Kind of Wonderful further

separates it from Pretty in Pink and signals another

departure from

the upward-mobility format. Apart from the protagonists

and their close friends (Duckie and Watts), the other

members of their social class involve themselves

to different degrees.

Andie’s friends – save Duckie – mysteriously

disappear thirty minutes into the movie, obviating the need

to include them in the conclusion of the film. All the audience

hears from them is, “Andie are you going out with a

rich man?” before they vanish and Andie stands oddly

alone. Duckie, unimpressed with her decision to cross the

class barrier, protests, “They’re gonna use everybody,

including you,” but by the end he admits, “You’re

right, Andie, he’s not like the others.” In Some

Kind of Wonderful, Keith has no friends but Watts as the

movie starts, but the disenfranchised come out in full support

once he is linked with Amanda Jones. Issues of class segregation

give way to vicarious male sexual fulfillment (“Hey,

by the way, congratulations, dude, man, she’s smoking”)

and pure class revenge, as when Duncan crudely says to Keith, “Congratulations

on your latest coup…Anytime somebody from the outside

lifts a woman from a guat like Jenns, man, we can all find

cause to rejoice…Punch her apron one time for me.” A

riot-like class frustration animates the small army that

supports Duncan at Jenns’ party, where they intervene

to protect Keith. Whereas, in Pretty in Pink, Andie’s

fellow working-class students simply disappear, Some

Kind of Wonderful paints the working-class support for Keith in

vengeful terms. The poor do not want to become or even avoid

the rich in Hughes’ version of 1987; rather,

they want to destroy them. The irremediable anger is

commensurate

with

a plot structure that refuses to resolve class conflict.

If the final showdown and reconciliation in Pretty

in Pink occur at the very institutional prom, the adult

institutions

are powerless to mediate in Some Kind of Wonderful.

What

remains is a private party with no supervision.

The imaginary geography of upward mobility, the physical

space in which the romantic coupling of the poor

protagonist and her or his rich love interest is

permitted to occur,

also shifts between 1986 and 1987. In Pretty

in Pink,

neutral space is the only locale for inter-class

romance. On their

first date, Blaine and Andie attempt a party at his

wealthy friend’s enormous house and a working-class nightclub,

and both crowds refuse them. Blaine takes Andie home, where

the goodnight kiss and their first real connection take place

not on Andie’s porch or in Blaine’s BMW, but

on the street, between the two zones. For their next on-screen

meeting, they are banished to the stables of Blaine’s

parents’ country club. When Blaine approaches Andie

in her corner of the schoolyard, he feels uncomfortable,

saying, “I don’t think I’m very popular

out here.” Likewise, when Andie confronts him in the

hallways of the school, he asks, “Can we talk about

this later?” This trend, built up throughout the film,

relaxes in the re-shot ending, when Duckie is romantically

approached by a rich girl on the dance floor at the prom.

Conversely, when Duncan’s working-class army attempts

a similar move at Jenns’ party at the end of Some Kind

of Wonderful, the rich girls roll their eyes in disgust,

and – however humorous the presentation – there

will be no conciliation, no common ground. Significantly,

the only kiss that Keith and Amanda share takes place on

the stage of the empty Hollywood Bowl, all emphasis on the

supreme superficiality of the event in a space of performance,

in a city of illusion and transitory celebrity. By the film’s

end, the link between the poor boy and the apparently

rich girl is erased when Keith chooses to close the

film out

with his lower-class, tomboy friend Watts in his arms.

Some Kind of Wonderful’s moratorium on upward mobility

reverses the happy ending of Pretty in Pink and is echoed

unendingly in the decade that follows. This rupture was partnered,

at the time of its filming, with another change in John Hughes’ usual

mode of operation. Until Some Kind of Wonderful, every movie

Hughes had made had been shot in or around Chicago, Illinois,

where he was raised. “Chicago is what I am,” Hughes

said during interviews to promote Ferris Bueller’s

Day Off in the summer of 1986, as Sharon Barrett reported

in the Chicago Times; Hughes went on to reiterate that he

would continue filming his movies in Chicago. However, within

weeks of that interview, locations for Some Kind

of Wonderful were finalized in San Pedro and Hollywood, California. This

move may not seem significant, but it represented a stunning

change from established form, since the vast majority of

upward-mobility stories mentioned above focus on the Steel

Belt or the Big Apple, loci of blue-collar industry or of

white-collar Wall Street. Once Hughes stepped westward, he

abandoned the teen-film genre completely, but the films and

music that soon emerged did so in the western states. The

dark comedy, Heathers (1989), a classic of teen anger that

launched the careers of both Shannen Doherty and Christian

Slater, takes place in southern California. Cameron Crowe’s

Say Anything (1989) and Singles (1993), and the emergence

of grunge music and its slacker ethos in the form of Nirvana,

Pearl Jam, and Alice in Chains took place in Seattle. Songwriter

Beck wrote the Generation X anthem, “Loser,” in

Los Angeles in 1992, after moving back there from New York

City (its classic chorus repeats: “Soy un perdedor/I’m

a loser, baby”). Richard Linklater chronicled the X-ers

of Slacker (1991) and the X-er prototypes of Dazed

and Confused (1993) in Austin, and Ben Stiller’s Reality

Bites (1994)

was also set there. Teen movies generally stayed west, until

Kevin Smith moved them to the Garden State in Clerks (1994)

and Mallrats (1995), and Larry Clark’s disturbing Kids (1995) took place in New York City. Hughes’ move

to Los Angeles for Some Kind of Wonderful somehow coincided

with the extrication of the teen movie from the upward

mobility

story.

Ultimately, reading Some Kind of Wonderful as a narrative

of upward mobility emphasizes the manner in which

it refuses such mobility. The ending to Some

Kind of Wonderful is

so different from the final moments of Pretty

in Pink that we

have to wonder how Newsweek’s David Ansen actually

could have watched both films to their conclusion and

still insisted that they were the same. In two works

so evidently

about class and the lines between classes, it matters

very much that in one, the poor girl gets the rich

boy, and

in the other, the poor boy selects instead a member

of his own

class. DeMott, who ignores the narrative structure

of the two films, likewise misses this key distinction.

The ending

that Hughes had tried to hitch to Pretty in Pink in

1986

had been shot down by his test audiences; one year

later, it was given the green light, grossing a respectable

$19 million on a miniscule production budget.

Bernstein opines, in his comments on Some Kind

of Wonderful, that it lacked the “youthful naiveté” of

its predecessor: “The picture just seems a little tired.” Typically,

films that dealt with social mobility or inter-class romance

into the early 1990s did so either cynically or in a manner

that empowered the lower-class characters. Consider Say

Anything,

in which an entire scholastic rise is rendered dubious when

the protagonist’s father is incarcerated for having

supported her with embezzled money. In Mystic

Pizza (1989),

Julia Roberts, a waitress, informs her Porsche-driving lover

that he is “not good enough” for her; at the

end of the film, she leaves him in the kitchen to perform

assembly-line cooking tasks while she relaxes on the porch.

Pretty Woman (1990) sees Roberts forcing the acrophobic Richard

Gere to climb her fire escape to win her back. These pictures

play on the same wish-fulfillment fantasies omnipresent in

the films examined above from the early years of Reagan’s

presidency, but class relations have shifted. The rich

boys are made to work for the love of their poor girlfriends,

who dictate the terms.

When measured against the economic and political

background that informed them, American cinematic

representations

of class and social mobility in the early 1980s appear

generally

to mirror their environment. The critical blindness

to a crucial difference between two of the more prominent

examples

of such representation in the teen subgenre – Pretty

in Pink and Some Kind of Wonderful – whitewashes a

moment of national rupture and misses a critical opportunity.

In and around 1986, the national psyche had shifted from

the money-driven optimism and positive perception of the

rich that prevailed during the early Reagan years to a pessimistic

economic outlook and lost trust in the very president who

had embodied the former optimism and materialism. The mid-

to late-1980s approached the topic of wealth and its attainment

with a great deal more suspicion. This jaded perspective

of upward mobility becomes an integral part of the ethos

of Generation X, the generation raised on movies like those

of John Hughes; the so-called “slacker” culture

of the early 1990s represents just the most extreme

example of this disillusion.

September 2006

From guest contributor Geoffrey Baker |