The Harriet Tubman and the Frederick Douglass quilts are little-known national treasures. Created in the early 1950s by an interracial group in California, these quilts were on the cutting edge of the enormous political and cultural changes that would soon rock our country. And they are important landmarks in the history of American quilting art.

“The Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman quilts are the earliest examples I know of quilts made with an overtly political purpose,” says Patricia Turner, quilt expert and professor of African American and African studies at the University of California, Davis. “They are also the first portrait quilts created in the African American quilting tradition. Today, there are hundreds of quilters using the media to make political statements. Lots of portraits, lots of political content. But the Tubman and Douglass quilts were made decades before all this.”1

Both the Douglass and Tubman quilts are huge — each about eight by ten feet. Each quilt took nearly two years to create. Both were painstakingly fashioned with intricate needlework and close attention to historical detail by a unique group of individuals, many of whom had never made a quilt before. They were men and women, black and white, church-going and atheist, working class and bohemian. They had joined together to study African American history in the late 1940s — years before Rosa Parks refused to go to the back of the bus, and decades before the first African American Studies course existed. They were the Negro History Quilt Club of Marin City and Sausalito.

The story of the History Quilt Club, and how these groundbreaking quilts came to be made, is a tale woven of many threads. It’s a story born in the West Coast shipyards of World War II with their unprecedented workplace equality. It’s the story of an unusual town that grew up around one particular shipyard where people of all races lived together in integrated public housing. It’s the story of pioneering African American intellectuals including W.E.B. Du Bois. And it’s the story of how history and politics and geography and culture can converge to inspire astonishing works of art.

Just five miles north of San Francisco, across the Golden Gate Bridge in Marin County, is a small crescent-shaped valley surrounded by rolling hills of gold and green. This valley, with its mild climate, abundant acorns from the oaks that dot the landscape, and fish-rich waters of the nearby bay, was once home to the Miwok Indians. Later, dairy farmers grazed their stock on the grassy lowlands. For centuries, this tranquil valley remained secluded from its bustling neighbor to the east — Sausalito.

Sausalito is perched on the shore of San Francisco Bay. Throughout the 1800s, the picturesque town grew as wave after wave of sailors, explorers, and settlers dropped anchor and stayed for a while. By the mid-1800s, Sausalito boasted hotels, shops, saloons, a newspaper, and a Methodist church. In the early 1900s, wealthy San Franciscans and summertime vacationers discovered the excellent swimming, fishing and yachting of Sausalito’s welcoming waterfront. Artists and assorted free spirits were drawn to the cheap rents and great views — not to mention the city’s tolerant attitude towards bookmaking, opium smoking, and rum running. When the Golden Gate Bridge opened in 1937, automobile access between San Francisco and Sausalito brought more people each day.

And all the while, the bucolic valley just west of town remained quiet — a world apart.

Then came the bombing of Pearl Harbor and everything changed.

After suddenly entering World War II in December, 1941, the United States needed to build a fleet of war-ready ships and tankers. The tidal mudflat at the northern edge of Sausalito was chosen as the site for a new shipbuilding facility. Laboring round the clock, workers filled in the marsh with dirt from a nearby hill, and drove thousands of pilings into the landfill. Buildings, shipways, piers, and a ferry slip were constructed. Railroad tracks were laid, and a mile long channel was dredged. In only three months, the mudflat had been transformed into a bustling shipyard. It was named Marinship.

Drawn by well-paying war industry jobs, 20,000 workers flocked to Marinship. Most were poor blacks and whites from the South and Midwest. African Americans had the added incentive of wanting to escape the racism they were subjected to in the segregated South.

“Back where I was from in Louisiana, I earned $1.20 a week,” remembers 88-year-old Rodessa Battle. “At Marinship, I earned $1.20 an hour!”2

Not only were salaries better in wartime industries, but all workers received equal pay for equal work. This unprecedented workplace equality was ordered by President Roosevelt who stated, "There shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin." Shipyards, ammunition plants, airfields, supply centers, and other government-run facilities were ordered to end employment bias.

At Marinship, over half the workers were women and minorities. Welders, carpenters, riveters, electricians, pipe fitters, and painters all worked side by side for equal pay, regardless of gender or ethnic background. This wage equality promoted a feeling of comradeship. In record time, Marinship workers built ninety-three vessels, including fifteen Liberty Ships — the gargantuan cargo vessels so vital to the war effort. Marinship became known as the best-integrated shipyard on the West Coast.

But there was a huge problem: Where would these thousands of workers and their families live? War-time housing was extremely scarce. The answer? Build it. The perfect spot? The bucolic valley just steps from the new shipyard.

So, as Marinship was being constructed, so was Marin City. Seven hundred apartments, 800 detached homes, and 1,000 dormitory rooms went up lickety-split. The new town, dubbed Marin City, provided shelter for 6,000 residents. Blacks, whites, Asians, and Latinos all lived together in integrated public housing. Marin City had a weekly newspaper, church, post office, library and schools. It had a hospital, grocery store, drugstore, beauty salon and barbershop. It even had a soft drink and candy shop. The dormitory facilities for single workers provided twenty-four hour housekeeping service, game rooms, gymnasium, coffee shop, and cafeteria.

“In those days,” remembers Marin City resident Bea Hayden, “there were a lot of different nationalities here — Arabians, Egyptians, everybody. It was like a melting pot. We were just a bunch of people trying to make a living.”3

Beatrice Johnson remembers: “We all knew one another. We looked out for one another, the children and houses…If it rained, and you were out somewhere, your neighbor would take your clothes in for you and put them in the house.”4

Adds Bea

Hayden, “There was no crime, no stealing — nothing like that.”

But Marin City’s heyday, remembered in idyllic terms by many residents, lasted only a few years. At the end of the war, the Marinship shipyard was decommissioned and shut down. War-related employment evaporated, and workers were forced to find new jobs. Some families returned to their original pre-war homes, but most preferred to stay in the Bay Area, which posed a unique problem for African Americans. Alexander Saxton, retired history professor and a resident of Sausalito at that time, remembers: “Back then, Marin County was completely segregated. Housing segregation was strenuously enforced both by local banks and real estate people. White people could find new housing around the county, but Marin City was the only place open to black people. So that’s where they stayed.”

“They wouldn’t sell to blacks anywhere in the county,” recalls Flossie Berry. “We just stayed in the old war housing.”5

Max Beagarie moved to Marin City with his family in 1950, when he was eight years old. The Beageries were one of the few white families to settle in Marin City once the shipyard had closed. “My parents were very politically conscious. They met during the 1930s in the fight for unions and for unemployment benefits. My father traveled throughout the West, distributing the Daily Worker [the Communist Party newspaper]. Later, he worked as a printer and my mother worked in the fishing industry. At the end of the war, we moved to Sausalito. It was a really cheap bohemian artists’ colony. Then we moved to Marin City. In Marin City, we lived in public war housing, which was starting to dilapidate. Most of the kids were from the South, black and white. Some Mexicans. It was a big mix of cultures. There was some racism in Marin City, some whites didn’t like blacks and vice versa, but I had friends from every background. Over the years, most of the white families left Marin City, and it became predominantly black…and poor.”

While Marin City became primarily African American, neighboring Sausalito remained almost completely white. Max Beagerie’s mother, Claudia, joined a study group that brought residents of Marin City and Sausalito together. Max stated, “My mom was in an integrated group, black and white, trying to create a school of African American history. They wanted to resurrect that buried history."

"It was a group of progressive political people,” recalls Jack Berriault, a Sausalito resident at that time. “We were all working for the rights and acknowledgement of black people before it was fashionable. We had relationships with people in Marin City, which by then was almost entirely black.”

One member of the study group was Ben Irvin, an architect and muralist who worked at an architectural firm in San Francisco. It was Ben’s idea to create a quilt honoring African American history. Recalls Alex Saxton: “Ben organized the quilt project. The quilting team consisted of black women from Marin City and white women from Sausalito. My recollection is that there was already a quilting club among African American women in Marin City. The white radicals came to it through the Negro History Week movement.”

Negro History Week, precursor to Black History Month, was the brainchild of Carter G. Woodson who was the son of former slaves. He worked his way up from the coal mines of Kentucky to the University of Chicago, eventually earning a Ph.D. at Harvard. He joined the faculty of Howard University where he became Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Troubled that history books ignored African Americans, Woodson dedicated his life to rectifying this situation. He wrote extensively about blacks in America; he founded the Journal of Negro History; and in 1926 he launched Negro History Week.

The purpose of Negro History Week was to honor the contributions of African Americans and to encourage cultural pride. At that time — a time when the Klu Klux Klan had over 100,000 members, lynchings in the South were still commonplace, and Martin Luther King, Jr. had not even been born — this was a radical idea. Woodson chose the second week of February for this celebration because it included the birthdays of both Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln.

Negro History Week was championed by the most influential African American of the first half of the 20th century — W.E.B. Du Bois. A sociologist, historian, civil rights activist, and prolific writer, Du Bois was the first African American to earn a Ph.D. at Harvard (the second was Carter Woodson). Du Bois co-founded the NAACP, and was editor-in-chief of its magazine for twenty-five years. His books, including The Souls of Black Folk and Black Reconstruction, changed how whites viewed blacks and how blacks viewed themselves. Throughout his life, Du Bois blazed his own trail. He debated with contemporaries Booker T. Washington and Marcus Garvey. He called for militant political protest and legal remedies to end racism in America. He advocated for union and labor rights, and equal rights for women. Eventually, Du Bois became an advocate of socialism, believing that economic inequality was as crippling to humanity as racial prejudice. At age ninety-three, Du Bois joined the Communist Party.

“Capitalism cannot reform itself,” stated Du Bois. “It is doomed to self-destruction. Communism — the effort to give all men what they need and to ask of each the best they can contribute — this is the only way of human life.” Du Bois also cited his approval of the Communist Party’s long-time stand against racial discrimination.

“The major organization for African Americans in Marin City was the NAACP,” recalls Saxton. “For white radicals in Sausalito it was the CP [Communist Party]. The CP had been actively campaigning against racial segregation for years. So, through the tradition and influence of W.E.B. Du Bois, these converged precisely on Negro History Week, which was strongly supported by both the NAACP and the CP.”

In 1949, the Negro History Club of Marin City and Sausalito began working on a quilt to honor black Americans. They chose Harriet Tubman as their subject. Their goal was to display the quilt at Marin City’s Negro History Week celebration.

“I can see why the History Club might have decided to create a quilt for Negro History week,” says quilt expert Patricia Turner. “Quilts are portable. They can be easily displayed for a show or exhibit, then folded up and put away. Also, they can be made communally. You can come up with a product by combining skill sets. Some group members might be able to sew. Each person contributed something unique. You can’t do this well with sculpture or painting.”

The History Club wanted to incorporate what they were studying about Harriet Tubman into their quilt. They most likely learned that Tubman, great heroine of the Underground Railroad, escaped from slavery when she was twenty-nine years old. She returned South, escorting members of her family, one by one, to freedom. After guiding her family to safety, she returned again and again to lead many more rescue missions, putting her own life and liberty at risk each time. Traveling by night, wearing disguises, and utilizing a series of “safe houses” provided by anti-slavery activists, Tubman led more than 70 slaves to freedom. After Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law, ordering officials in free states to capture and return escaped slaves, Tubman had to guide her fugitives all the way to Canada.

The History Club members probably also discovered that Harriet Tubman’s bravery did not end with the Underground Railroad. She used her extensive knowledge and networks to aid abolitionist John Brown’s insurrection against the slaveholders at Harpers Ferry. During the Civil War, she worked as a scout for the Union Army, and she was the first woman to lead an armed expedition in the war — freeing more than 700 slaves in the Combahee River Raid. After the war, she joined Susan B. Anthony in working for women’s suffrage.

“To pick Harriet Tubman as a subject for their quilt,” says Pat Turner, “rather than a less controversial, less confrontational figure such as Booker T. Washington, is indicative of the progressive politics of the quilters.”

History Club member Ben Irvin, with his background as an artist and muralist, came up with the design for the Tubman quilt. Next, the group constructed a huge frame to hold together the layers of the enormous eight by ten foot tapestry. Then the quilters got to work. Birdie Smith, Martha Johnson, Essie McKee, Betty DePrado, Catherine Holland, Margaret and Billie Jo Fuslier, Bernice Vissman, Detia Wright, Florence Shandeling, and Claudia Beagerie pooled their skills, using embroidery, appliqué, and other needlework techniques to create the quilt.

“I had done plenty of sewing before, but I didn’t know anything about quilting,” relates Margaret Fuslier. “Working out the design and putting the different parts together taught me so much about colors and patterns.”6

“When we worked together in the quilting bee, we talked about Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass too, and that’s the way we really get to know about our history,” states Birdie Smith.7

Adds Bernice Vissman: “It’s amazing how close you get to the quilts when you work on them. I scarcely knew anything about Harriet Tubman before, but now we all call her ‘Sister Harriet,’ and she’s a friend.”8

Quilts provide warmth as well as beauty. They are a medium of personal expression; a method of transmitting culture; a means of connecting generations, and of creating community. Although the circumstances of the History Quilt Club were unique, their process comes out of a long and rich quilting tradition.

Quilting goes back at least as far as ancient Egypt. Archeologists have discovered quilted floor coverings from 100 BC Mongolia, and knights in the Middle Ages were known to wear quilted garments under their armor. Women in Colonial America made quilts for bedding, often recycling old quilts as stuffing for new ones. The Tubman quilt would be considered a “story quilt,” such as those created by Harriet Powers, a former slave and folk artist, whose nineteenth century quilts depict scenes from the Bible and of astronomical phenomena.

Quilting bees, where people — usually women — get together to work on each other’s quilts, are a vital part of the American quilting tradition. More than simple work parties, quilting bees are social events. In nineteenth century America, they were a way for women in rural areas to break out of their isolation; a time to tell stories, exchange news, share food. And quilting has been important in the African American community, going back to the time of slavery.

But within this extensive and varied history, the Harriet Tubman quilt holds a unique position. States Patricia Turner, “I can find no earlier example of a portrait or a political quilt.”

Even quilters involved in the abolitionist movement — a precursor in many ways to the modern civil rights movement — kept their politics out of their quilts. “White women in the abolitionist movement were not allowed to go to meetings with the men,” explains Turner. “So they would get together in quilting bees to share information about the abolitionist movement. They would quilt together, and talk about politics together, but the quilts themselves were not political. They were traditional patterns.”

And beyond the innovative content of the Tubman quilt, the interracial composition of the group was also groundbreaking. While racially integrated quilting bees are not absolutely unheard of in American history, they are extremely rare.

The History Quilt Club of Marin City and Sausalito met several times a week, working on their creation for almost two years. It wasn’t just the intricate needlecraft that was time consuming: the huge frame had to be assembled and dismantled for each session. And there were supplies to buy — fabric, thread, needles, embellishments. The quilters’ husbands contributed to the project by cooking a special community dinner to raise funds to buy the materials.

Finally, in early 1951, the Harriet Tubman quilt was complete.

The tapestry depicts Tubman holding a rifle, her image larger than life-sized. She’s seen leading a group of slaves north towards freedom. Her clothing is historically authentic; the quilters even used embellishment such as real shoelaces to create her utilitarian work boots. Over Tubman’s shoulder is the North Star, which she used as a navigation tool while bringing fugitives through the dark night. Sitting on a branch beneath the star is an owl — symbol of Tubman’s wisdom and her shrewd knowledge of the night.

The quilt made a splash at Marin City’s 1951 Negro History Week celebration. It went on to win second place at the California State Fair of 1952, and it found an avid fan in historian/activist Sue Bailey Thurman who was a founder of the National Council of Negro Women and the editor of the Africamerican Women’s Journal. She and her husband, theologian Howard Thurman, traveled the world promoting intercultural understanding — including meeting with Mahatma Gandhi in India to discuss nonviolent resistance and social change.

Ben Irvin was acquainted with the Thurmans who lived in San Francisco. He showed the quilt to Mrs. Thurman soon after it was completed. Mrs. Thurman’s passion to encourage awareness of black history matched perfectly with her appreciation of the remarkable quilt. She took the Harriet Tubman quilt on a tour of the East Coast. The high point of the trip was when she displayed the quilt at Tubman’s home and gravesite in Auburn, New York.

While Mrs. Thurman was busy championing the Harriet Tubman quilt, the History Quilt Club was hard at work on their next project — a quilt featuring Frederick Douglass.

Like Tubman, Frederick Douglass had escaped from slavery. He educated himself, becoming a gifted orator, influential writer, and advisor to President Lincoln. He was a key leader in the abolitionist movement, giving fiery speeches against slavery. After the Civil War, Douglass was appointed Minister to Haiti. Also like Tubman, he became a strong proponent of women’s rights.

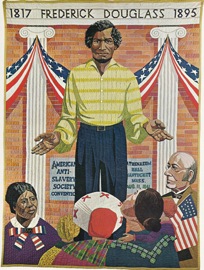

The Frederick Douglass quilt was an even more ambitious undertaking than the Tubman one. Using actual photographs as their guide, the quilters created portraits of Douglass, his wife Anna, and William Lloyd Garrison (another leading abolitionist). The tapestry shows Douglass giving a speech at the American Anti-Slavery Society convention. Mrs. Douglass and Mr. Garrison can be seen in the foreground. The place and date, Nantucket, Massachusetts, August 11, 1841, are inscribed behind him. Having gained valuable experience from their first project, the quilters expanded their techniques. In addition to cotton, they used silk, lace, and velvet to piece and appliqué the quilt. Brick wall, fluted columns, banners, flag, clothing, hair, and faces are all done with exquisite detail, giving each element its own realistic texture and feel. Subtle shadings make the faces of Douglass and the others come to life.

After working on the Frederick Douglass quilt for nearly two years, the quilters finally displayed their creation during Marin City’s Negro History Week of 1953. The public was invited to watch the quilters in an “arts-in-action” booth where they put the finishing touches on the quilt.

The History Quilt Club had big plans for the future. They intended to create a series of quilts honoring historical figures — from ancient Egypt’s Pharaoh Ikhnaton, to their contemporaries, including W.E.B. Du Bois. However, as it turned out, the Frederick Douglass quilt was their last. Why? In all my research — in books and periodicals and videos, in phone conversations and emails and in-person interviews with people who remembered the history club or had some connection to it — I was never able to find out exactly why the club disbanded. And I was never able to find any surviving members of the club itself.

Luckily, we still have the quilts.

Both the Harriet Tubman and the Frederick Douglass quilts were purchased in the 1950s by the Howard Thurman Educational Trust Foundation. They were exhibited at the 1965 World’s Fair in New York; toured with the “Afro-American Art Show” of 1968; and were part of the “Freedom Now” exhibit of African-American history, art, and culture in the 1970s. The Thurmans later donated the quilts to the Robert W. Woodruff Library at the Atlanta University Center in Atlanta, Georgia, where they hang on permanent display today.

NOTES

1. All quotes are from interviews conducted by Eve Goldberg, unless otherwise noted.

2. Joan Lisetor, Marinship Memories, DVD, 2009.

3. Marilyn L. Geary, Marin City Memories, Circle of Life Stories, 2001, p. 27.

4. Ibid, p. 46.

5. Ibid. p. 56.

6. Negro History Bulletin, April, 1953, p. 151.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

January 2015

From guest contributor Eve Goldberg