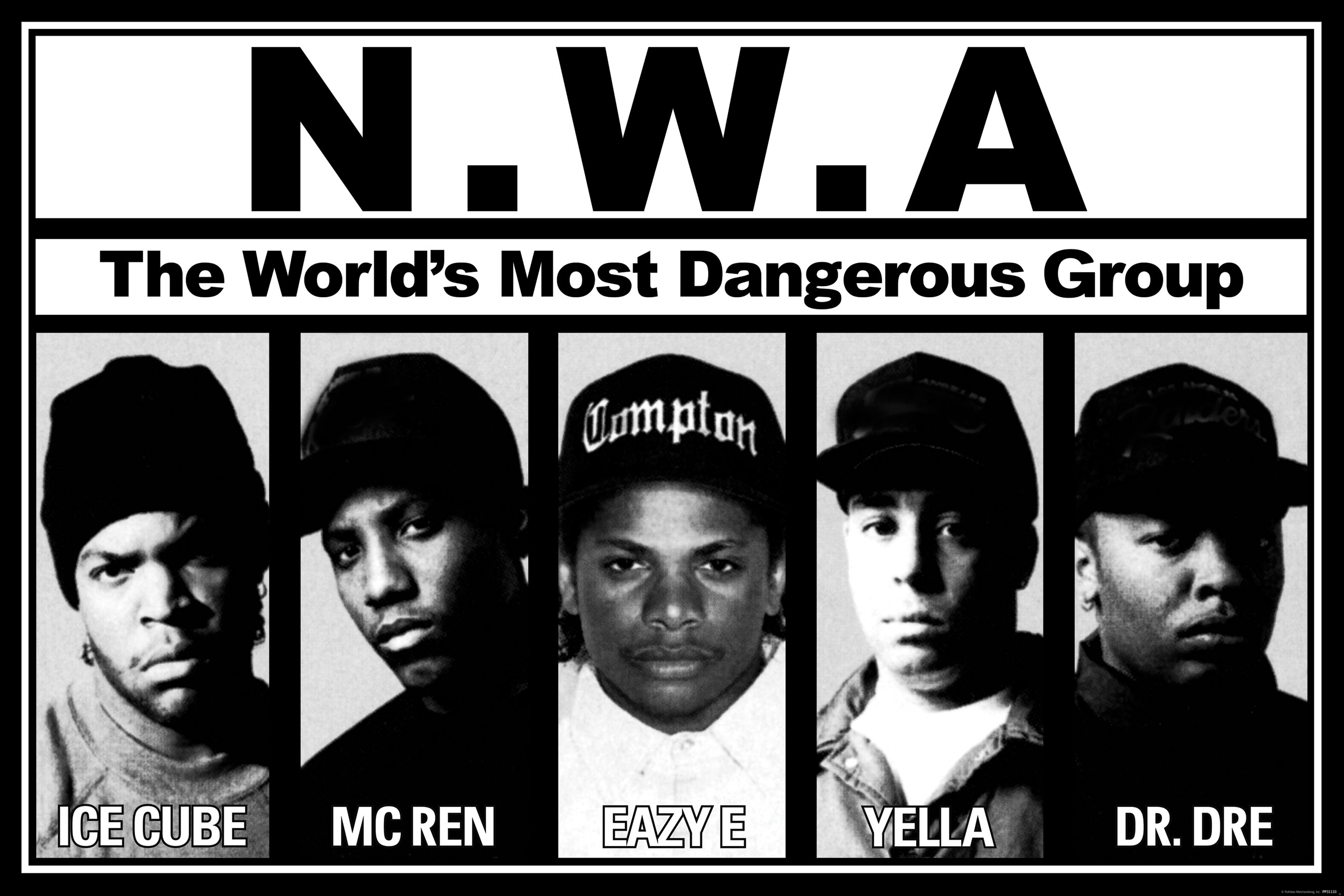

This essay examines cultural works, especially works of protest, through a nobrow approach. I study two African-American protest works, namely, Richard Wright's canonical novel Native Son (1941) and NWA (Niggaz Wit Attitudes)'s popular gangsta rap album Straight Outta Compton (1988). Violence is a key theme in both works and is effectively displayed through the African-American "badman" figure. I argue such brutality exposes readers and listeners to cross-cultural voices regarding race and racial injustice.

Nobrow Culture and Nobrow Audience

The concept of cultural classification is a recent invention in American culture. In America's Coming-of-age (1915), Van Wyck Brooks expresses his discontent over the absence of "genial middle ground" in American life. He finds Americans to be lacking of communal solidarity because they are either striving for "vaporous idealism" or "self-interested practicality." Brooks describes such extremes as "two irreconcilable planes." Since then, highbrow and lowbrow have the polarizing connotations of intellectuality and business respectively. On the other hand, a nobrow approach believes significant art cannot be organized by cultural hierarchy. As I shall further elaborate, all cultural works are possibly valuable in nobrow culture.

Nobrow, nevertheless, is not middlebrow and does not attempt to realize Brooks' wish of bringing the two planes together. The formation of middlebrow culture depends on the recognition of cultural categories, and aims to make high culture accessible to the masses. For Dwight Macdonald, both "masscult" (lowbrow) and "midcult" (middlebrow) cultural products are in "total subjection to the spectator" due to their lack of standards. In 1942, Virginia Woolf similarly criticizes middlebrows as pseudo-art lovers who are "in pursuit of no single object, neither Art itself nor life itself, but both mixed indistinguishably, and rather nastily, with money, fame, power, or prestige."

However, other critics have found Macdonald's and Woolf's contempt towards middlebrow as problematic. Russell Lynes' satirical essay "Highbrow, Lowbrow, Middlebrow" (1949) includes a detailed list of activities considered to be highbrow, lowbrow, and middlebrow to poke fun at American society's obsession with cultural standards. Simon Stewart even finds Woolf's remarks as "snobbish" and deems such rigid cultural classification only further cementing the elitists' supreme position as the authority of culture.

A nobrow approach avoids the culture wars by viewing art through a browless lens. Nobrow culture is highly market-oriented as opposed to categorizing culture based on elitist standards. John Seabrook explains that the hierarchy of culture is replaced by the hierarchy of "hotness" in the world of nobrow. Due to hyper-marketing in the contemporary age, culture is commercialized, and the masses consume culture to define their identities according to what is popular and interesting in the market. As Seabrook explains in the essay "Nobrow culture" (1999), "In the old high-low world, you got status points for consistency in your cultural preferences, but in Nobrow you get points for choices that cut across categories." "Good" cultural products are defined in terms of market popularity, and the public decide what is popular or "hot."

Peter Swirski also explains nobrow culture in terms of market demand, but from the producer's standpoint. Nobrow, for Swirski, is "an intentional stance whereby authors simultaneously target both extremes of the literary spectrum." He finds lowbrow cultural works, especially in the field of literature, removing cultural boundaries as they "invade and explore every literary niche" in order to survive the keen competition in the book market. As writers have always been under socioeconomic pressure, Swirski locates the emergence of nobrow culture in the early twentieth century when Van Wyck Brooks first proclaimed the distinctions of high and low.

A key difference between Seabrook and Swirski lies in the reception of nobrow works. Swirski does not necessarily find nobrow as equal to hot and popular. Due to their nature to appeal to both extremes of the literary spectrum, nobrow works refuse clear-cut categorization and are, therefore, difficult to be marketed and promoted. Whereas highbrow, lowbrow, and middlebrow works aim at their respective audiences, Swirski's nobrow writers appeal to both high/low readers by ambitiously incorporating elements of highbrow and lowbrow beyond the confinements of the brows. Nobrow works like Raymond Chandler's Playback (1958) therefore "fall through the cracks" because, Swirski would argue, they are simultaneously "too pulpy for the intellectuals, too intellectual for the masses."

My understanding of nobrow combines the findings of Seabrook and Swirski. I contend authorial intention alone will not result in the formation of nobrow. While Swirski's nobrow writers reject cultural classification by incorporating elements of high and low, the hybrid nature of nobrow works will only be recognized in the presence of a nobrow audience that goes beyond the brow hierarchy as well. In this sense, I find Seabrook's concept of nobrow as market-oriented similar to reader response theory. In The Act of Reading (1978), Wolfgang Iser argues "the significance of the work...does not lie in the meaning sealed within the text, but in the fact that the meaning brings out what had previously been sealed within us." The meaning of a work is only complete when the writer, the reader, and the text come together in the construction of the work's meaning. Seabrook's nobrow audience first approaches all works, including nobrow works, without cultural pretense and then decides what is "hot."

This nobrow collaboration between writers and audience is particularly important to works of protest, which aim to challenge or even shape sociopolitical paradigms by way of literary art. In terms of race, institutional racism in America was made illegal with the passing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, as well as the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Nevertheless, the outlaw of racism does not eliminate discrimination related to race. As Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic argue in Critical Race Theory, racial injustice is tied to a "broader perspective that includes economics, history, context, group and self interest, and even feelings and the unconscious." Scholars of the post-Civil Rights Movement era reveal a wide range of current social injustice still extant. Cornel West argues that America's long history of racial oppression towards African-Americans leads to "black invisibility and namelessness." For example, statistics show beneficiaries of the Civil Rights Movement, especially educated blacks, climb the social ladder. Yet marginal socioeconomic groups, argues critic William H. Chafe, such as the African-American teens represented in the lyrics of NWA's Straight Outta Compton, are even further marginalized after the Movement. A deeper, nobrow, understanding of race is developed through different perspectives, mediums, and voices.

Redefining the "Bad" in Badman

The badman is a folkloric figure of violence who has existed in traditional African-American ballads since the late nineteenth century. Roger Abrahams describes the badman figures as "murderers and thieves, sadistic in their motivation,...looking for a fight just to prove their own strength and virility." One of the most popular badman figures is Stagolee, also known as Stacker Lee, Stagger Lee, Stackalee, Stackolee, Stack-O-Lee, Staggalee, Stack-O, and Stack Lee. Stagolee's story is reinterpreted in many versions of the badman ballads, which explain the numerous variants of his name. Each version of the lyrics contains similar graphic details of Stagolee's murder of his friend Billy Lyon and capture by white sheriffs.

In the version collected by John Lomax, the ballad begins with a fatal altercation between Stagolee and Billy Lyon during a gambling session. Stagolee first coldly dismisses Billy Lyon's plea for mercy because he has got "five lil helpless chilluns an' one po' pitiful wife." Stagolee then shoots Billy Lyon five times, including three times in the forehead, and proclaims he will "keep on shootin' till Billy Lyon died." After the murder, Stagolee takes joy in traumatizing Billy's wife by showing her "de hole" in Billy's head. The white sheriffs are immediately alerted about the murder. They pursue and capture Stagolee. They first try to hang him, but "his neck refused to crack." All the sheriff's panic. They finally shoot him six times to execute him. After his burial, Stagolee is seen in hell: "Stagolee took de pitchfork an' he laid it on de shelf - "Stand back, Tom Devil, I'm gonna rule Hell by myself."

Stagolee proudly continues his notorious role of a bully in hell. He insists on retaining his individual freedom even in his afterlife. He refuses to be overpowered by anyone, including the devil. He is a murderous psychopath who proclaims to "rule Hell" by himself in his afterlife. He is a ruthless bully in the eyes of his black neighbors, white law enforcements, and even the devils from hell. Yet African Americans, or any marginalized race, can relate to Stagolee's story; they are regularly persecuted or oppressed.

On one hand, readers may suggest one doesn't need to be as bad as Stagolee to be prosecuted. On the other hand, the outrageously "bad" nature of Stagolee forces readers to inquire as to the source of Stagolee's violence. Martin Luther King Jr. highlights the influence of the oppressor towards the oppressed: "It is incontestable and deplorable that Negroes have committed crimes; but they are derivative crimes. They are born of the greater crimes of the white society" (1967). Some readers are tempted to accept Stagolee, and even celebrate him as a black anti-hero who represents African Americans' desperate desire for individualism and strength in a racially oppressive society. This seemingly conflicted perception towards Stagolee also rejects John W. Robert's insistence on dividing the badman figure into two types according to their motivations: the outlaw hero badman, and the destructive badman, or "bad n----r." Motivation cannot be fully recovered. And regardless of their intentions, both the badman and the bad n----r resort to violence and destruction that cause damage to whites and blacks. The fine line between hero and villain ultimately depends on the reader's interpretation.

Without a doubt, the badman represents violence, danger, and a threat to society as a whole. But the idea of "bad" is complicated when viewed in the context of protest against racism. The badman's shockingly destructive nature upsets core social values and raises awareness towards ideological issues like racism. As the invisible becomes visible, readers are encouraged to further explore the relationship between the badman's violence and racism. My examination of the badman figures in Native Son and Straight Outta Compton thrives on this ambiguity of "bad"; I view them as flawed protagonists who are products of sociopolitical issues like racism.

In "How 'Bigger' Was Born" (1940), Richard Wright reveals his determination to avoid Native Son from becoming a novel "which even bankers' daughters could read and weep over and feel good about." Instead, the novel has to be "so hard and deep that [readers] would have to face it without the consolation of tears." Wright effectively achieves his goal in Bigger Thomas, the young African-American underclass male protagonist of Native Son. One of the murders that ultimately cements Bigger's status as one of the most gruesome figures in African-American badman literature involves Bigger suffocating his affluent white employer's daughter, Mary Dalton, with her own pillow. He then dismembers her body before cremating it in the furnace.

Nearly fifty years later, Ice Cube, the main rapper of NWA, portrays himself as an equally dangerous figure from the streets of Compton, Los Angeles, in Straight Outta Compton. In the first four bars of the album's opening track "Straight Outta Compton," Ice Cube immediately displays his ultra-violent, psychopathic personality:

Straight outta Compton, crazy motherf---er named Ice Cube

From the gang called Niggaz Wit Attitudes

When I'm called off, I gotta sawed off

Squeeze the trigger and bodies are hauled off

These four bars establish the setting and thesis of Straight Outta Compton. The album takes place in the inner-city, poverty-stricken area of Compton. The protagonists are the "crazy motherf---er" Ice Cube and his gang NWA. Street violence quickly follows with Ice Cube describing his immediate response when he is agitated ("called off"); he needs to take out his "sawed off" shotgun and shoot his enemies until their bodies are "hauled off."

Both Bigger Thomas and NWA are developed from the badman archetype. The audiences are brought in to directly observe their murderous crimes, which are no less shocking than Stagolee's execution of Billy Lyon. The public may dismiss such graphic details as sensational, vulgar, and "lowbrow." Tipper Gore, the co-founder of the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC), infamously labels the lyrics of gangsta rap as a "glorification of violence." Native Son, despite its well-respected status amongst literary critics, was listed as one of the most frequently challenged books of 1990–1999 by the American Library Association. I argue the violence depicted in the two works serves more of a sophisticated awakening towards the social, collective violence of racism.

Bigger Thomas and the Native Badman

After a failed attempt to rob a white-owned store, Bigger in Native Son is desperate for money and unwillingly takes a job with the affluent and white Dalton family as their chauffeur. The daughter, Mary Dalton, orders Bigger to drive her to see her communist boyfriend, Jan. Mary asks Bigger to keep her relationship with Jan a secret as the Dalton's are a capitalist family. She is drunk after the date and Bigger struggles with whether to help Mary to her bedroom or leave her in the car. He does not wish to betray Mary's secret, and perhaps more importantly, he cannot contain his "excitement" towards the charming Mary.

Bigger decides to carry Mary to her bedroom. His thoughts begin to show signs of double consciousness: "He felt strange, possessed, or as if he were acting upon a stage in front of a crowd of people." Bigger understands, as an impoverished African-American male, he would be "out of character" and possibly be fired from his job if he is seen having physical contact with his rich employer's white daughter. Bigger's struggles precisely echoes W.E.B. DuBois's definition of double consciousness: "two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder." Bigger adamantly ignores the "crowd of (white) people" and stays true to his identity. He defies white laws and expectations like a typical badman by helping Mary to her bedroom.

Bigger indulges further into his own feelings as he takes the drunken Mary closer to her bedroom. He is sexually aroused from the physical contact with Mary. When they reach the bedroom, Bigger can no longer repress his desires towards Mary: "He tightened his fingers on her breasts, kissing her again, feeling her move toward him. He was aware only of her body now." At this moment, the visually impaired Mrs. Dalton enters Mary's room. He is paralyzed by the fear of being discovered in a white girl's bedroom. He is well aware that society will accuse any black man of raping a white woman simply because he was inside her bedroom.

Although Bigger knows Mrs. Dalton is blind, he is terrified by the possibility of Mary making any sound which would alert Mrs. Dalton of his presence. In the heat of the moment, Bigger uses a pillow to cover Mary's mouth. Yet his fear of Mrs. Dalton, as well as the mainstream society, overrides his initial intention of merely muting Mary. Bigger eventually suffocates Mary to death. The blindness of Mrs. Dalton satirically alludes to how whites consider African Americans as invisible, or what Toni Morrison describes as the rejection of the "Africanist presence." Bigger's fear towards a blind Mrs. Dalton serves as a powerful metaphor of the lethal impact racism has towards both blacks and whites alike.

It is only after Mrs Dalton leaves the room that Bigger realizes the horrendous crime he has committed: "she was dead; she was white; she was a woman; he had killed her; he was black; he might be caught; he did not want to be caught; if he were they would kill him." Racism continues to infect Bigger's mind. He is convinced that society will execute him regardless of what he has to say. Under such desperation, Bigger resorts to what he refers to as "the safest thing of all to do." He decides to burn Mary's body in the Dalton's house furnace. The body, however, is too big for the furnace. Bigger commits an even greater act of brutality by decapitating Mary's corpse. Bigger asks himself before dismembering the body, "Could he do it?," to which he coolly replies, "He had to." His response is simultaneously shocking and thought-provoking. He is stating that he must decapitate and burn the body of his employer's daughter.

Rather than immediately dismissing Bigger as an inhumane, bloodthirsty, monstrous animal, readers instinctively question Bigger's "logic." And once readers trace back through Bigger's internal thoughts, they reveals that his very gruesome action is only a human response to a desperate situation: Bigger is an African-American underclass male living in a racist society that views him as invisible and persistently threatens to strip away his freedom. Bigger's logic hence is shaped by his fear, shame, and anger as a marginalized member of American society. Mary's death signifies the birth of Bigger as a "bad n----r" who vows to destroy anyone who challenges his individualism. Yet Native Son's limited third person narration allows readers to examine Bigger's transformation from an African-American underclass male to a heinous, violent, and murderous monster. As Jerry H. Bryant comments, Native Son focuses on "the danger of the young falling prey to the corrupted streets and becoming predatory badmen." Our attention is subtly relayed from the product to the cause; from the bad n----r to racist society; from the native son to America.

NWA and Badmen with Attitude

In Straight Outta Compton, NWA continue to explore the relationship between the badman and his social surroundings. In several interviews, they call themselves "underground reporters" and their songs are "documentaries." Unlike traditional news reporting that tells the news story in the third-person, NWA use the first-person. Eithne Quinn notes how this "eye/I" dialect displayed in gangsta rap is rooted in African-American slave

narratives: "this [first person] perspective enhance[s] reader identification, thus personalizing the institutionalized violence and exploitation of the slavery system." By closing the distance between artist and his art, Cooper states, NWA are "simply thrust[ing] their listeners into the middle of the street and leave[ing] them to fend for themselves."

Ice Cube, Dr Dre, Eazy-E, and MC Ren essentially become the "news" regarding anti-police sentiments and gun violence in their Compton neighborhood. The eye/I perspective heightens the element of shock in Straight Outta Compton and perhaps explains the huge amount of backlash which surrounds the group. The most notable controversy certainly points to the second song on the album, "F--- Tha Police." In 1989, the FBI issued an unprecedented official letter accusing NWA of encouraging "violence against and disrespect" for law enforcement officers in Straight Outta Compton and primarily due to the song "F--- Tha Police."

"F--- Tha Police" is set in a courtroom trial complete with court officer, judge, prosecuting attorneys, witness and defendant. Yet the trial is organized by the "NWA court." Fellow NWA collaborator DOC plays the role of a court officer and announces the beginning of the court session. He introduces Dr Dre as the judge who presides over the case of NWA versus the Los Angeles Police Department. MC Ren, Ice Cube and "Eazy-motherf---ing-E" are announced as prosecuting attorneys. More profanity and absurdity follow. Ice Cube somehow also serves as a witness in the trial. Dr Dre orders Ice Cube to testify against the Los Angeles Police Department:

DR DRE: Order, order, order. Ice Cube, take the motherf---ing stand. Do you swear to tell the truth, the whole truth. And nothing but the truth so help your black ass?

ICE CUBE: You godd--n right!

DR DRE. Well won't you tell everybody what the f--- you gotta say?

The subversive nature of "F--- Tha Police" is clear even before any rapping is introduced. Rather than describing the above scene merely as a mock courtroom trial, its reckless neglect of judicial practices and coarse language indicate the song is more of a mockery towards a racially biased legal system. The US prison system has long been infamous for its disproportionate incarceration of minorities, and the trend appears to have experienced a rapid growth in the 1980s and 1990s, according to Theodore Caplow and Jonathan Simon. More than half of young African-American men from poor inner cities were in the criminal justice system. Listeners should approach the profanity and bloody altercations in "F--- Tha Police" with the above sociopolitical context in mind.

Ice Cube, MC Ren, and Eazy-E then deliver a string of fantasies about violent retaliations against police brutality. For example, Ice Cube describes himself as a "young nigga on a warpath" that will leave "a bloodbath of cops dying in LA." MC Ren admits "taking out a police would make my day." Eazy-E offers a disturbing answer to his question about the LAPD: "Without a gun and a badge, what do ya got? A sucker in a uniform waiting to get shot." Yet in the midst of this seemingly endless stream of attacks against the LAPD, the NWA rappers manage to juxtapose their verbal assault with sociopolitical protest. Ice Cube's opening couplets effectively demonstrate this juxtaposition:

F--- the police coming straight from the underground

A young nigga got it bad cause I'm brown

And not the other color so police think

They have the authority to kill a minority

F--- that s---, cause I ain't the one

For a punk motherf---er with a badge and a gun

To be beating on, and throwing in jail

We can go toe to toe in the middle of a cell

Ice Cube explains how young African-Americans are mistreated, and even murdered, by Los Angeles law enforcements because of their brown skin color and minority status. Brian Cross observes that the LAPD "has since its inception been the front line in the suppression of people of color in [Los Angeles]." Apart from racial bias, both Cross and Quinn would argue, the continuous militarization of the LAPD since 1950 coupled with its lack of accountability to any independent review body resulted in the "genuine resentment, fear and rage" that NWA attempt to convey. Ice Cube swiftly and furiously denounces such institutionalized racism. He describes a police officer as a "punk motherf---er" who can abuse black youths like him simply because he has "a badge and a gun." But if Ice Cube finds the police officer imprisoned with him, he will "go toe to toe" and fight him inside the prison cell.

After the three NWA rappers/prosecuting attorneys have given their testimonies, the song concludes with Dr Dre announcing on behalf of the NWA court that the LAPD is guilty of being a "redneck, white bread, chickens--- motherf---er." An LAPD police officer is forcefully removed from the court while repeatedly pleading for justice. This dramatic, and even humorous, ending completes NWA's attempt to retaliate against the discriminatory judicial system with their own "NWA court" that follows the laws of the streets.

Protest Without Boundaries

Violence as a means of racial protest is a major motif in Native Son and Straight Outta Compton. Yet mainstream society's reception towards the two works is contrastingly different. Not only was Native Son a bestseller upon its immediate publication, it was also the first African-American novel to be adopted by the Book-of-the-Month Club. Although the adopted version had censored its sexual passages, the theme of racism as depicted by the graphic details of Bigger's crimes was still intact.

After Native Son was published in its complete form in 1991, Time magazine, amongst other prominent mainstream publications, included the book in its list of 100 best English-language novels published since 1923. In terms of sales, Straight Outta Compton was triumphant, having reached double platinum sales status with little promotion. Yet much of its commercial success was due to the FBI's attempt to censor the album, Terry McDermott claims. And while academic scholarship on gangsta rap and hip hop is evidently growing, the genre remains shunned by mainstream society for what Bryant terms its "angry defiance, its callow, calculated violations of mainstream manners and values." Tipper Gore's superficial remarks of gangsta rap as simply a "glorification of violence" still echoes in the public.

Both Native Son and Straight Outta Compton have evoked the badman folkloric tradition to protest against racial injustice. Although Richard Wright and NWA utilize different approaches in reenacting the badman figure, their underlying objective of making racism visible to the public remains the same. Some may argue it is precisely the difference in approaches that establishes the grounds to assign Native Son and Straight Outta Compton into high/low classifications. On the contrary, I contend difference, or diversity, is key to racial protest.

Native Son's limited third-person narration of Bigger's shocking crimes and internal thoughts was certainly successful in raising social awareness regarding racism. But racism is ever-changing, especially after the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Eduardo Bonilla-Silva coins the term "new racism" to describe how racism has become "sophisticated, covert, and apparently nonracial" in the post-Civil Rights era.

Society becomes gradually desensitized towards racism. NWA's offensive first-person rhymes are a continuation of African-American literature's mission to subvert the establishment's binary values and make racism visible again in contemporary society. Unfortunately, cultural categories confine readers' appreciation of alternative approaches in racial protest. The marginalization of gangsta rap and NWA denotes the importance of a nobrow reading that frees protest works from the limiting boundaries of highbrow and lowbrow.

July 2014

From guest contributor Michael Cheuk Ka Chi, The University of Hong Kong |