It’s hard to fathom, but Los Angeles’ Dodger Stadium is now the third oldest ballpark in major league baseball, trailing only venerable Fenway and Wrigley.

Built in 1962, and featuring plastic seats in sun-splashed yellow, orange and blue, acres of parking spaces, and palm trees tilting gently beyond the center field bleachers, Dodger Stadium is the crown jewel of mid-century ballparks. It’s a paean to the free’n easy Southern California lifestyle when a gallon of gas cost 32¢, surfers rode longboards, Barbie planned on being a stewardess, and Orange County had, well, a bunch of orange groves.

L.A.’s ballpark is as much a cultural fixture as the 405 Freeway or the Hollywood Bowl. The stadium has played host to The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Michael Jackson, the Olympics, and the Pope. Visions of Koufax stretching to release a blazing fastball, Maury Wills flashing to second on a steal, Valenzuela’s eyes rotating up into his head, Lasorda trotting out behind his pot belly to confront the ump, are an integral part of the city’s collective memory.

Less in the collective memory, but front and center in the mind of Frank Wilkinson, is another vision of Dodger Stadium – this one less breezy, less parti-colored, less about Bermuda grass. “It’s absolutely the tragedy of my life. I was responsible for uprooting hundreds of people from their own little valley and having the whole thing destroyed.” Frank Wilkinson’s vision of Dodger Stadium is one of backroom deals and secret memos, bulldozers and shattered lives. It’s a story of innocence and double-cross, of race and class and rat infestation and cops swinging batons. And Frank should know. He was at the center of it all.

On October 7, 1957, Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley signed a contract with the city of Los Angeles, trading a 9-acre stadium site he had previously purchased for a 315-acre site near downtown L.A. Just two years after their jubilant World Series victory over the Yankees, Brooklyn’s beloved Dodgers – dem Bums, the boys of summer – were gone. The Trauma of Brooklyn is a story that has been told and retold: the deterioration of Ebbets Fields, the demographic shift to the suburbs (and the West), the protracted clash between Robert Moses and O’Malley, the aborted Atlantic/Flatbush proposal, the effigies of O’Malley burning in the street. It’s a quintessential narrative of power politics in which ordinary folks are the perennial losers.

But long before O’Malley ever considered moving his ball club out of Brooklyn, another battle was being waged – this one in Los Angeles – which would ultimately decide the fate of the Dodgers. At issue was a hilly, wooded parcel of land just north of downtown L.A. known as Chavez Ravine.

Shantytown or Shangri-La?

Set in a basin of undulating hills dotted with walnut and oak and palm, Chavez Ravine of the 1940s was home to some 300 families – mostly poor Mexican Americans. Comprised of three small villages (La Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop), the community was tight-knit and tradition-filled. Residents ran their own schools and churches, grew their own food, and raised chickens and pigs. For generations, families thrived in this semi-rural hamlet. Just over the hill from downtown Los Angeles, it was a world apart.

“We were all like brothers and sisters,” remembers Carmen Torres in Don Normark’s book of photo essays entitled Chavez Ravine, 1949. “And the mothers were all like comrades you know, they baptized each other’s children,”

Delia Aguilar married into a Chavez Ravine family. “When I got married I walked all that street of La Loma in my bridal gown and veil. I was an outsider, but it was like a family. Everybody came to the wedding. Everybody ate. They all knew each other.”

“Those houses were small,” Tony Montez recalls. “ When they had parties they’d put the furniture out in the backyard.”

“We didn’t even lock the doors. Leave everything open, toys outside,” adds Zeke Contreras. “Most everybody had chickens and rabbits and a few people had pigs and cows. There were horses roaming the hills, and goats. Like being out on the open range.”

But one person’s Shangri-La is another person’s shantytown. Following the National Housing Act of 1949, Chavez Ravine was slated for slum clearance; the rickety, rat-infested homes which often lacked electricity or toilets were to be replaced by a modern, full-amenities public housing project. “We received an allocation of $110 million from the federal government to build 10,000 units on 11 sites,” remembers Frank Wilkinson, then Assistant Director of the Los Angeles Housing Authority. “Chavez Ravine was the plum. It was our largest project. We hired world-class architects to design the housing. We planned to have childcare centers and beautiful parks. There was this wonderful, progressive idea to really make public housing a positive lifestyle change for low-income people.”

As odd as it may sound today, public housing was indeed once the domain of dreamers, idealists, and reformers. Frank Wilkinson was one of them. And, in a fateful meshing of character and history, Wilkinson would become the pivotal, if unwitting, figure in what came to be known as The Battle of Chavez Ravine.

From Beverly Hills to Watts

Born in 1914, Frank Wilkinson grew up in a strict, religious household in Beverly Hills. His father, a medical doctor, was a devout Methodist and conservative Republican whose civic involvement tended towards issues like the eradication of prostitution. Wilkinson Sr. co-founded the Citizen’s Independent Vice Investigating Committee, and supported Prohibition candidates for office. Rules at home included no drinking, no swearing, and no card playing.

Frank came of age during the Great Depression. Tall and handsome, with dark wavy hair and a winning personality, he set out on a path consistent with his upbringing. At UCLA, he was an SAE pledge, a leader in Youth for Hoover, and a member of the rowing team. “These were the Depression years, but I wasn’t at all concerned about poverty,” Wilkinson recalls in his six volume oral history, “Matters of Conscience,” compiled by Dale Treleven of the UCLA Oral History Program. “I never saw unemployed people; I never saw soup kitchens; I never saw begging. I just floated through the Depression oblivious to what was going on around me.”

Frank’s silver spoon youth was marred, however, by a progressive, congenital hearing disease. “From the age of twelve, my hearing was a handicap,” Frank remembers. “My hearing definitely began to restrict my interests. Debating and dramatics became impossible. At UCLA I simply could not hear the lectures.” Hearing aids in those days were clunky devices the size of a hotel Bible which hung around one’s neck like a boxy chest plate. “I wouldn’t even consider wearing a hearing aid. I looked down on people who wore them. I wanted to be popular. But I missed so much that my tendency was to control a conversation so I wouldn’t be caught with a question.” During his junior year at UCLA, Frank secretly drove down to Beverly Hills High at night. “I would sneak into the building through a back window, then sit at the very back edge of the classroom so that no one could see me, and take lip-reading classes.”

Despite his disability, Frank’s social life flourished. “I was famous for going to the Coconut Grove or the Biltmore Bowl on Friday night for dancing, but would order a bottle of milk. I was popular, but I was intellectually superficial, bluffing my way through so many situations when I couldn’t hear.” As a senior, he ran for student body president – representing the fraternities and the religious community against a liberal, secular candidate. “I made a decision that if I was elected student body president, I would publicly admit that I was hard of hearing and do something about it.” He lost the election.

Unable to join his father and older siblings in the medical profession, Frank decided to become a Methodist minister. But first, after graduating college in 1936, he and a fraternity brother headed East. What began as a pilgrimage to the Holy Land became a profoundly life-altering journey. Eschewing hotels for sleeping bags, Frank bicycled and hitchhiked through Europe, North Africa, and the Mid-East for two years. He befriended Jews in Morocco, chatted with prostitutes in Egypt, argued politics with Algerian revolutionaries around a campfire in the Kabylian Mountains. He witnessed goose-stepping Nazis in Nuremberg, a pogrom in Rumania, and prisoners being marched through Moscow by Soviet police. “I was terribly ignorant, and then suddenly the world just opened up.” Frank lost his political innocence watching Texaco oil tankers pump fuel into Nazi tanks helping Franco’s fascists in Spain (so much for FDR’s official position of neutrality!). He lost his religious innocence in Bethlehem on Christmas Eve – amidst the beggars, the children with running eye sores, the antagonistic sects seething around the Church of the Nativity.

“When I returned to Beverly Hills, it was like culture shock. I didn’t want to sleep in my soft bed after spending so many nights sleeping under bridges or on sidewalks.” Frank announced to his family that he was an atheist. He bought a hearing aid. He walked naked around the house. When he received a traffic ticket, he chose to spend the weekend in jail rather than pay the $5 fine. He joined a picket line at the Hollywood Citizens News. His family was alarmed.

In another era, a bright, rebellious 24-year-old with no job prospects and plenty to say might form a rock band or start a blog. Frank – with his father’s encouragement – hit the lecture circuit. Between 1938 and 1941, he made hundreds of appearances, recounting his world travels to every Rotary, Kiwanis, Optimist, and Lions club in Southern California. In the years before television, Americans were hungry for first-hand reports of what life looked and felt like in other parts of the globe. Frank delivered. He told stories of bloody battlefields in Spain, camel chases in Beirut, dictatorship in Greece, kibbutz life in Palestine. His stories from the Soviet Union – great opera, clean subway system, as well as blatant anti-Semitism and a good deal of poverty – ruffled feathers on both ends of the political spectrum. Frank quickly built a reputation as a much-in-demand public speaker. For a guy with a hearing problem, more comfortable talking than listening, it was a perfect fit.

Privately, Frank was painfully groping his way towards a new identity. He got a job doing manual labor at a pipe factory. He asked himself, “What are my ethics?” He married his college girlfriend, Jean Benson, the one person from his past who seemed to understand and support his startling changes.

And then the man who would change Frank’s life forever came knocking.

Monsignor Thomas O’Dwyer could have come straight out of Central Casting: the wise and loving priest with a soft smile and a gentle voice. But O’Dwyer, Director of Catholic Charities for the Los Angeles Archdiocese was no actor. He was the real deal. An indefatigable activist on behalf of the needy, he had formed the Citizen’s Housing Council of Los Angeles, an organization of reform-minded architects, builders, and clergy concerned with the establishment of decent housing for the poor. O’Dwyer approached Wilkinson after hearing him lecture about poverty overseas. Frank recalls how, in a pitch-perfect, end-of-the-first-act turning point, “Monsignor O’Dwyer told me that I didn’t need to go so far to find the same conditions. He took me eight miles from my lovely home in Beverly Hills to the slums of Watts. I was shocked. I couldn’t believe that we had housing conditions like this right here in Los Angeles.”

The budding crusader and the kindly priest teamed up immediately. Frank signed on as the Citizen’s Housing Council secretary – and chief agitator.

A Decent Home for All

In 1942, the Los Angeles Housing Authority (LAHA), an independent agency funded by the federal government, had just completed construction of three public housing projects: Avalon Gardens, Hacienda Village, and Pueblo del Rio. When it was announced that these projects would be segregated by race (one white, one black, one Hispanic), Wilkinson and O’Dwyer organized a silent protest vigil in front of Hacienda Village. The press arrived. “We walked up and down with our signs,” Frank recalls, “and after a period of time, the Housing Authority, embarrassed by this, gave in. A negotiator comes out and says, ‘Ok, we’re gonna mix them.’ And then he turns to me and says, ‘If you love n-----s so much, maybe you’d like to live with ’em. How would you like to be the manager here?”

Frank accepted the offer, going to work for LAHA as manager of Hacienda Village. “We turned the project into a real garden. Everybody grew flowers. And it was integrated – about one third black, one third Chicano, and one third white. We had playgrounds with jungle gyms and slides. Some of the kids had never seen flush toilets and they liked to put their little balls or boats in the toilet and see them go round and round. We had to initiate a fifty-cent charge for every stopped-up toilet.” At Hacienda Village, Wilkinson hired instructors to teach cooking, sewing, and house cleaning. The following year, as manager of Ramona Gardens, he brought in Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth to celebrate Cinco de Mayo festivities.

Just as Wilkinson’s segregation vigil unexpectedly catapulted him into a job with the very agency he had been criticizing, his second protest produced another unintended consequence. At a national convention of housing officials in Las Vegas, he learned that while the white delegates were staying in the Frontier Hotel, the black delegates were being bused to sleeping quarters fourteen miles out of town. Outraged, Frank and other liberal delegates refused to stay at the Frontier. Over the objections of his boss, Howard Holtzendorff, Frank made a motion on the convention floor that no future convention would use any segregated facilities. The motion passed. The following week, when Holtzendorff showed up at Ramona Gardens with a scowl on his face, Frank fully expected to be fired. Instead he was kicked upstairs, the new Assistant Director at LAHA.

As head of public information, Frank threw himself into the job of educating people about the need to create decent housing for the poor. He took busloads of wealthy Westsiders on tours of South L.A., hoping they’d be moved as he had been when confronted directly with the stench of open sewers, the sight of children eating on dirt floors. As liaison with the U.S. Census Bureau, he canvassed every single block of the city, mapping out areas of sub-standard housing. He personally escorted L.A.’s mayor, Fletcher Bowron, on a tour of his city’s slums in the Goodyear blimp.

An LAHA report written by Wilkinson, entitled “A Decent Home, An American Right,” lays bare the culture of public housing at the time. The cover art, in a kind of Socialist Realism meets the American Dream, with the requisite bold diagonals and muscular geometric accents, depicts four men – three in military uniform, one with hard hat and lunch pail – striding confidently away from a seedy tenement and into a pleasant suburban tract. The report itself, rich with pie charts, maps, organizational tables, and photo essays informs the reader that “Good Housing Means Good Citizenship” and “Bad Housing Breeds Crime.” Over a photo montage of tree-lined streets, happy children, picnics, and factory workers, the reader learns that “Religion, Home, School, Work, Recreation, Free Speech and Culture are THE AMERICAN WAY OF LIVING…FOR ALL PEOPLE.” One page lists city ordinances which support public housing; another page of statistics details exactly where the projects will be built and who will pay for them. The report is nothing if not earnest, hopeful, and well researched. As far as Frank Wilkinson could tell, the future of public housing looked rosy.

But the national mood was shifting. Following World War II, in a prolonged and often cacophonous segue, the words of President Roosevelt (“The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much, it is whether we provide enough for those who have little...”), rang out under the incoming clatter of Senator Joseph McCarthy (“I have here in my hand a list of 205 people that were known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping the policy of the State Department...”). It was in the midst of this sea change that public housing development went into high gear. In a last gasp of New Deal air, Congress passed the National Housing Act of 1949, mandating, "…a decent home and suitable living environment for every American family." Flush with $110 million from Washington (the equivalent of one billion dollars today), Wilkinson was put in charge of site selection for upcoming projects in Los Angeles. “We had a dream,” he reminisces, “that L.A. would be the first city in the U.S. to be free of slums.”

Believing that the comforts of suburbia should not be solely the domain of the affluent, Wilkinson decided to relocate poor families from mixed-use, industrial areas to new, medium-density residential communities. He determined that the 12,000 residents of the blighted industrial triangle around downtown should be moved, not to the distant avocado orchards of the San Fernando Valley, but right over the hill to Chavez Ravine.

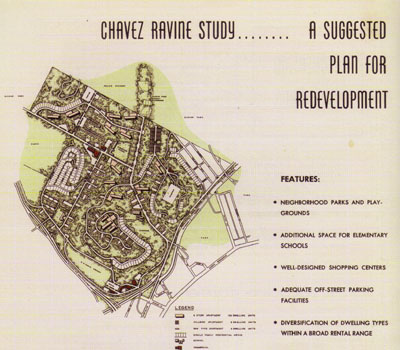

Architects Richard Neutra and Robert Alexander were chosen to design the prestigious Chavez Ravine project – which they dubbed with characteristic optimism “Elysian Park Heights.” Neutra brought with him a ton of modernist cred. He had apprenticed with Erick Mendelssohn in Berlin, spent a three-month sojourn at Taliesin with Frank Lloyd Wright, and designed an unrealized urban utopia which he called Rush City Reformed. His first public housing project, Channel Heights, was a low-rise community of garden apartments, schools, and shops overlooking the Pacific in San Pedro, just south of Los Angeles. Alexander had been involved in designing Baldwin Hills Village, a residential community of row houses and apartments with private patios, garden courts, and a central village green. The layout meshed communal and private spaces in a tree-lined, pedestrian friendly design. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of the complex – a nod even in 1937 to the growing omnipotence of the automobile – was that all 627 units had easy auto access and private parking garages. With their shared vision of a new urbanism – democratic, integrated, human-scaled, green – Neutra and Alexander were ready to take on the biggest challenge of their careers.

“Chavez Ravine,” a play by Latino theatre collective Culture Clash, dramatizes the ten-year civic war which transforms a canyon community of Mexican immigrants into a hilltop baseball stadium. The play, commissioned by the Mark Taper Forum, premiered in 2003. A little bit vaudeville, a little bit Brecht, “Chavez Ravine” employs music, humor and biting social satire in a magical concoction that stays true to the tenor of the times. Many of the characters are based on real-life personalities. Frank Wilkinson is portrayed as a well-intentioned, but hopelessly ethnocentric, do-gooder. In one early scene, an ebullient Wilkinson leads a huffing and puffing Richard Neutra up into the hills above downtown. “Aren’t these rolling hills of Chavez Ravine a perfect site for a brand new housing project? The sunshine! The fresh air! …These are just the people who can benefit from your modular, low-slung, abstractly asymmetrical buildings!” Wilkinson gushes. Neutra is not so sure.

Back in the real world, as the 1950s dawned, Elysian Park Heights began to take shape. Working in the clean-lined, minimalist vernacular of modern architecture, Neutra and Alexander envisioned a blend of urban and suburban elements: two-story apartment buildings with private gardens would be spread out between several elegant high-rise towers. The community would also include schools, kindergartens, day care centers, churches, community hall and kitchen, indoor and outdoor auditoriums, and parks.

The designs were reviewed enthusiastically by the mayor, the city council, and Wilkinson. Neutra and Alexander, however, registered ambivalence about the entire endeavor. Both architects were dubious about interfering with what they viewed as a “charming” area of happy, well-adjusted families who took great pride in their tradition-filled community.

Also skeptical about City Hall’s plans for their community, were the residents of Chavez Ravine. Frank’s job was to convince them that a drastic transformation of their thriving hamlet was a good thing. He took on the task with gusto, believing whole-heartedly in his vision. For Frank, it was a simple equation: slums out – decent housing in. Teaming up with the two of the most powerful institutions in the community, the Catholic Church and the Communist Party, Frank went door to door, reassuring each family that after a period of temporary re-location, they would have first dibs on the new and improved housing. Then, wielding the power of eminent domain which enables government to purchase private property for the public good, the City of Los Angeles began condemning, buying up, and demolishing the neighborhood.

Are You Now Or Have You Ever Been...

But a powerful knot of business interests wasn’t going to allow 300 acres of prime real estate right next to downtown to be turned into integrated public housing. Enter CASH, the Committee Against Socialist Housing. Enter the Los Angeles Times. Enter Police Chief Parker, known for his brutality and racism. Enter the FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover who had been keeping tabs on Wilkinson since 1942. Cue the personal attacks against city councilmen who favor Elysian Park Heights. Cue an onslaught of editorials linking public housing to “creeping socialism.” Cue the rumors that Frank Wilkinson is a Communist.

On August 29, 1952, while Frank was testifying in a routine eminent domain hearing about Chavez Ravine, an attorney for the real estate lobby suddenly pulled a dossier out of his briefcase and stood up. “Now Mr. Wilkinson, will you please tell us what organizations, political or otherwise, you have belonged to since 1931?” Stunned, Frank turned to his LAHA attorney who shrugged. Frank answered – detailing his professional associations, but refusing to reveal his political affiliations which, he stated, were irrelevant to the issues at hand. At which point the situation swiftly deteriorated. The hearing was suspended; the City Council immediately passed a resolution calling upon the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) to investigate; and the courtroom filled with news reporters.

“In thirty minutes,” Frank recalls, “I went from being one of the more respected citizens in city government to being a total outcast.”

The next day, he was suspended from his job.

The headlines screamed: LID BLOWS OFF HOUSING, WILKINSON REFUSES DATA ON TIES, and SUSPEND L.A. HOUSING AID. For months, the Frank Wilkinson affair was front page news. When HUAC came to town several months later, Wilkinson and two other housing officials refused to answer the Committee’s questions about their political affiliations. All three were fired.

Mayor Bowron, public housing’s best friend for years, was feeling the heat. The Los Angeles Times relentlessly hammered away at his ties to alleged communist Wilkinson. In the municipal election of 1953, Bowron was challenged by Congressman Norris Poulson who ran essentially on an anti-public housing platform. Backed by CASH and the Los Angeles Times, Poulson promised to end “un-American housing projects.” Poulson defeated Bowron after a contentious fight. With Poulson at the helm, the city bought back Chavez Ravine from the Federal Housing Authority, then cancelled the Elysian Park Heights project. By now, nearly all the families of Chavez Ravine had been uprooted, scattered throughout Southern California, from Pacoima to El Monte, San Pedro to Boyle Heights. With the exception of a few hold-out families, Chavez Ravine lay idle – a ghost town awaiting its unknown future.

While the people of the Chavez Ravine diaspora began to construct new lives, Frank Wilkinson looked for a job. His wife, Jean, supported the family with her job as a teacher. Frank became a house-husband, taking care of the domestic chores and caring for their three small children. “I vacuumed. I ironed. I cooked. I organized the shelves. I organized the drawers. I organized the closets. I tried to figure out what to do with my mind.” When Jean was called before HUAC, she refused to answer the Committee’s questions, citing her right to privileged husband-wife communication. After thirteen years as a teacher in the Los Angeles public school system, she was fired.

This was the height of the anti-Communist crusade in America. HUAC had first made a name for itself in 1947, questioning members of the motion picture industry about their politics. A defiant group of ten men – writers, directors and producers – refused to cooperate. They challenged HUAC’s right to probe their personal beliefs. They became known as the Hollywood 10. Cited for contempt of Congress, they were sentenced to one year in prison. HUAC returned to Hollywood in 1951, this time calling dozens of writers, directors, producers, actors and studio executives to testify. Those who refused to cooperate, known as "un-friendly witnesses,” were blacklisted by the studios, unable to work for years.

Following the movie industry’s lead, most American corporations, universities, labor unions, and other institutions blacklisted those who either openly identified as a Communist or even, in many cases, people who were merely controversial. Jean Wilkinson turned out to be just the first of dozens of Los Angeles city school teachers who were called before HUAC, refused to cooperate, and were fired from their jobs.

After Jean’s dismissal, the Wilkinsons’ financial situation became dire. Frank’s old friend and mentor, Monsignor O’Dwyer, offered parish funds to help out. Finally, after ten months of searching for a job, Frank was hired by a sympathetic Quaker to work in his Pasadena department store as the night janitor.

As Frank Wilkinson cleaned toilets for a dollar an hour, the amazing, controversial, outspoken Jackie Robinson Brooklyn Dodgers were making their ascent to the pinnacle of the baseball world. In 1952 and 1953, they won the pennant, only to lose to the hated Yankees in the World Series. Finally, in 1955, they won it all, vanquishing their arch-rivals in October. All of Brooklyn was ecstatic. But even as the champagne was being uncorked, Dodger owner O’Malley was making plans to move his team. His first choice was to build a new stadium in Brooklyn. But after months of fruitless meetings and contentious memos between O’Malley and the city of New York, negotiations broke down for good.

At about this time, L.A. came knocking. Mayor Poulson and his backers were eager to bring a baseball team to Los Angeles. O’Malley didn’t need much convincing. The Dodger owner struck a deal with the city to trade a nine-acre lot in South Los Angeles which he had purchased some years back, for 315 acres in Chavez Ravine. O’Malley would finance the stadium himself. The city would kick in $2,000,000 for site improvements. O’Malley would own the stadium and the land. (Sweetheart deal, anyone?) A series of taxpayer lawsuits ensued. Celebrity stadium supporters such as George Burns and Groucho Marx weighed in on the issue. Stadium opponents were called “baseball haters.” Countless city council meetings about the proposed ballpark were marked by increasing rancor. Ultimately, the issue was put before the voters in a public referendum. Several days before the election, actors Ronald Reagan and Debbie Reynolds appeared on a Dodger Telethon urging voters to vote YES on Prop B. The stadium proposition passed by a slim margin. Chavez Ravine now belonged to O’Malley. All that stood in his way were some twenty families, steadfastly hanging on to their little piece of paradise.

On May 8, 1959, in perhaps the signature moment of the Battle of Chavez Ravine, sheriff’s deputies forcibly evicted the last remaining families of La Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop. TV cameras caught the action as children wailed, turkeys, and chickens shrieked, an elderly woman threw stones at the police, and two women were carried kicking and screaming from their clapboard home.

Four months later, a battalion of bulldozers moved into the ravine. Everything – Solano School, Palo Verde School, and the Santo Nino Church; the malt shop in Bishop, the liquor store, and the water tank where teenagers used to hang out; the rickety shacks and tin roofs and crooked fences; the fruit trees and mustard plants and squatty palms; the streets Paducah, Malvina, Reposa, and Davis; Yolo Drive and Spruce Avenue; the hillsides where wild horses and goats once roamed; everything – was methodically buried under eight million cubic yards of dirt.

By the time Chavez Ravine was filled, leveled, and ready for actual stadium construction, Wilkinson had been called twice more to testify before HUAC. He had also found a new calling, dedicating himself to civil liberties issues, cris-crossing the country to support others who were being persecuted in the McCarthy witch hunts. When Frank himself was called again before HUAC, he joined forces with the American Civil Liberties Union, offering himself up as a test case. He refused to answer the Committee’s questions, standing on his First Amendment right to freedom of belief. “As a matter of personal conscience and responsibility,” his statement to the committee began, “I challenge the fundamental legality of the House Committee on Un-American Activities.” After taking the case all the way to the Supreme Court, Wilkinson lost in a 5-4 decision. An article in the New York Times, dated May 2, 1961, reads: “Two men who have been active in efforts to abolish the House Un-American Activities committee have begun one-year prison sentences for refusing the answer questions of the committee.” Frank spent nine months in federal prison. Two months after his release, Dodger Stadium opened for business.

Frank Wilkinson spent the next forty-five years of his life working to defend civil liberties. He formed the National Committee to Abolish HUAC and witnessed victory on that front in 1975. He directed the National Committee Against Repressive Legislation and the First Amendment Foundation. He received the Roger Baldwin Medal of Liberty, the American Civil Liberties Union Eason Monroe Courageous Advocate Award, and the Earl Warren Civil Liberties Award. In 2005, after decades of sticking to his First Amendment right not to answer the question, “Are you now or have you ever been…,” he came out publicly as once being a member of the Communist Party. And, following years of personal boycott against the ballpark at Chavez Ravine, Frank finally became a Dodger fan, attending games with friends and family, but always painfully aware that buried below the bleachers there was once a community…and that lost among the ruins of that community there was a dream – a dream full of paradox and modernist ethnocentricity – a dream of making clean, decent, integrated public housing a reality.

In an article for Frontier magazine, written in the aftermath of the 1965 Watts Rebellion, Wilkinson wrote, “Had our plans been allowed to bear fruit, tens of thousands of African-American and Mexican-American children would have been lifted out of the stifling pressures of the ghettos, into the good air of integrated, beautifully designed, low rent communities. Year after year, tens of thousands more would have followed, and we could have begun the process of reintegrating the old ghetto areas – areas that burst into flame in the uprising of 1965 [and 1992, ed.], and are even more isolated and run-down today.”

Frank Wilkinson died in 2006, at home, at the age of 91.

May 2010

From guest contributor Eve Goldberg

|