“Did you know that the Baby Ruth candy bar was not named after baseball great Babe Ruth? It was named after Ruth Cleveland, the daughter of President Grover Cleveland.”

I carried that nugget in my back pocket for years, pulling it out now and then to enliven many a flagging conversation. The story goes that President Grover Cleveland’s daughter Ruth, known widely as “Baby Ruth,” was immensely popular at the time the Baby Ruth candy bar was created by the Curtiss Candy Company. One variation includes the vignette of little Ruth Cleveland visiting the Curtiss Candy operation at one point in her brief life.

Imagine my reaction when I first stumbled across accusations that the Ruth Cleveland story was untrue - a deliberate fabrication concocted to protect Curtiss Candy from potential claims by Babe Ruth. If that allegation was true, then I was a dupe, an unwitting shill for the Curtiss Candy Company merchandising machine. Throwing myself into the literature, I discovered a split between pro-Ruth Cleveland and pro-Babe Ruth factions, with neither side providing a well-reasoned or convincing analysis based on substantiated facts.

There is no dispute that Curtiss Candy claimed that Ruth Cleveland inspired the name for the candy bar. Pro-Ruth Cleveland sources blindly accept that claim on its face. The more vocal pro-Babe Ruth faction rejects the Ruth Cleveland story as pretext, based primarily on the conjecture that, given the Babe’s obvious fame, the candy maker must have been seeking to capitalize on his name. Curtiss Candy counters that the Babe was not, at that early point in his career, the monumental figure he would later become.

I determined to resolve the dispute once and for all. I would ruthlessly (sorry) eliminate the distortion of hindsight from the inquiry, putting myself back in 1919 – the dawn of the mass communications age when the country was bound together not by television, radio, and airplanes, but by newspaper, telegraph, and railroads. It is critical to examine the popularity of both Ruth Cleveland and Babe Ruth in historic context, at a specific point in time – the year Curtiss Candy introduced the Baby Ruth candy bar.

The basic facts are simple and largely undisputed. Ruth Cleveland was born on October 3, 1891, between Grover Cleveland’s two discontinuous terms as president. A toddler in the White House was a novelty, and she became popularly known as Baby Ruth, much as President Kennedy's son would later be known to the nation as “John-John.” Ruth left the White House at the end of her father’s second term in 1897 and died tragically of diphtheria at the age of twelve in January 1904.

The Baby Ruth candy bar was created by Chicago candy entrepreneur Otto Schnering and his Curtiss Candy Company. Schnering launched Baby Ruth in November 1919, pricing the log shaped caramel, peanut, and chocolate bar at five cents – half the price of other candy bars on the market. The candy bar proved immensely popular, due largely to Schnering’s marketing genius. He dropped thousands of Baby Ruths fitted with tiny parachutes from airplanes over Pittsburgh and other cities. In one typical Schnering marketing coup, Baby Ruth was selected and promoted as the official candy bar of the world-famous Dionne quints. In 1949, Time magazine dubbed him the "Candy Bar King" of the United States.

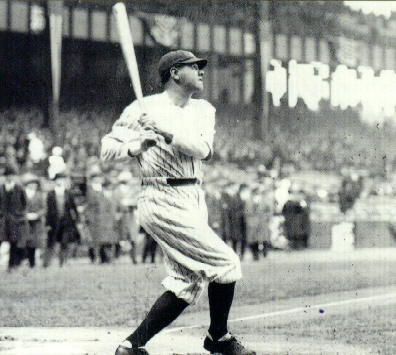

When the Baby Ruth was first introduced in late 1919, George Herman “Babe” Ruth had just finished his fifth and final season with the Boston Red Sox. He would be traded to the New York Yankees in January of 1920. Although only twenty-four years old, the Babe had already helped pitch the Red Sox to championships in 1916 and 1918, recording three World Series wins against no losses and logging a then-record twenty-nine consecutive scoreless World Series innings. At the plate, he had already broken the single season home run record by hitting twenty-nine in 1919, while still winning nine games as he transitioned away from being exclusively a pitcher.

From 1926 to 1931, Babe Ruth and Otto Schnering battled in the courts over trademark issues relating to the name “Baby Ruth.” However that litigation did not involve Schnering's alleged misappropriation of the Babe’s name. Rather, it centered on Schnering’s claim that the Babe’s own candy bar, “Babe Ruth’s Home Run Bar,” and his trademark application for the words “Ruth’s Home Run” interfered with the Curtiss Candy Company’s pre-existing trademark of the words “Baby Ruth.” The inspiration for the name of the Baby Ruth candy bar was not at issue and was expressly held to be irrelevant in the litigation. Schnering won the lawsuit and the court denied the Babe’s trademark application, effectively ending Babe's career as a candy bar magnate.

It would be harshly ironic if the Ruth Cleveland story was a fabrication and Curtiss Candy not only misappropriated the Babe’s name, but then used that misappropriation to stop the Babe from marketing a candy bar in his own name. However, it was in the court records of that long-neglected case that I discovered the single most compelling piece of evidence in the long debate over the inspiration for the name “Baby Ruth.”

At first blush, Otto Schnering’s insistence that Babe Ruth was not the inspiration for the candy bar appears almost absurd. Ruth Cleveland had been dead for fifteen years when the candy bar was introduced, and Babe Ruth was an established star in America’s national pastime. But the fact that time and chance have reduced Ruth Cleveland to a historic footnote today does not preclude her from having been a rock star in 1919, nor should we allow Babe Ruth’s current status as an American icon to distort our appreciation of his public stature in 1919.

In 1919 there was no such thing as “all news–all the time,” much less “all sports–all the time,” media coverage. News and sports were reported primarily by newspapers. A nationwide radio communication infrastructure existed, but average households were not direct consumers of those radio broadcasts. By 1921, only five commercial radio stations existed in America, providing scant coverage in a few urban areas. With the beginning of radio's Golden Age a decade in the future, fewer than 5% of American households had radios in 1920.

If, as Otto Schnering’s detractors claim, Babe Ruth was already a household name when the candy bar was launched, it was not through the medium of radio. The Babe’s achievements were witnessed live only by those attending the games. It would be a mistake to view these events though our twenty-first century prism and assume that media coverage of his twenty-nine home run season in 1919 compared remotely to the coverage of Roger Maris in 1961 or Mark McGuire in 1998.

On the other hand, it would be equally narrow-minded to suppose that Babe Ruth and Ruth Cleveland could not have become nationally famous, even household names, through the primary news medium of the day – the daily newspaper. In 1919, the nation was connected physically by railroads, and information was disseminated to newspaper publishers nationwide via telegraph and radio. This increasingly effective communications network created the first wave of national sports figures, as fans from coast-to-coast followed the exploits of Jack Dempsey, Big Bill Tilden, Bobby Jones, and the Babe. The era would become known as the Age of Heroes.

Newspapers created this initial class of national sports celebrities, and we can use those newspapers to test Otto Schnering’s claimed inspiration for the name of his candy bar. How famous were Ruth Cleveland and Babe Ruth in 1919? Was their relative fame such that an objective reasonable person (me, for instance) must conclude that Schnering’s Baby Ruth story was no more than a self-serving fabrication?

The Fame Index - Ruth Cleveland

Giving Otto Schnering his due, newspapers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries frequently referred to Ruth Cleveland as “Baby Ruth.” Her 1904 New York Times obituary recalled that “she was known to the Nation as ‘Baby Ruth’ while she was a child in the White House.” In addition, Ruth moves up on our unofficial “fame index” by having various things, animate and inanimate, named after her. “Baby Ruth” namesakes include a cocker spaniel in the 1895 Westminster Kennel Club show, an ice racing yacht competing in a 1893 New Jersey frozen river race, and a harness racing horse (or horses) trotting in Illinois and New Jersey in 1899 and 1900. These namesakes support Schnering’s assertion of Ruth Cleveland’s fame, at least up to the early years of the twentieth century.

Given this historic record, I accept the fact of Ruth Cleveland’s fame, and I do not dismiss out of hand Schnering's claim that she was the inspiration for the candy bar. However, Schnering and Curtiss Candy must answer for their patently impossible claim that Ruth Cleveland visited the Curtiss Candy plant when the company was getting started. Ruth Cleveland died in 1904, more than ten years prior to the founding of Curtiss Candy. The company’s earliest candy-making efforts did not occur until 1916 and took place on a kitchen stove, not in a factory. Further, while Otto Schnering would prove himself a gifted entrepreneur as early as 1916, he was only twelve years old when Ruth Cleveland died in 1904.

It is tempting to consider this intentional deception as proof per se that the candy bar was not named after Ruth Cleveland. Indeed, some commentators consider this big lie fatal to the company’s credibility. Nevertheless, I am inclined to give Otto Schnering the benefit of the doubt here. Records indicate that the source of the Ruth Cleveland fantasy visit was a 1973 reply by Curtiss Candy to an inquiry from one of Babe Ruth’s many biographers, Kal Wagenheim. Otto Schnering had been dead for twenty years when Curtiss Candy replied to Mr. Wagenheim. I find no record that Schnering himself claimed that Ruth Cleveland had any contact with the company and believe it unlikely that a man of his intelligence would concoct such a demonstrably false story. Accordingly, I dismiss the Ruth Cleveland visit fantasy as either an internal Curtiss Company legend or a misguided effort, long after the fact, to bolster the company’s long-held, but shaky, version of the Baby Ruth story.

Another purported link between Ruth Cleveland and the candy bar involves a commemorative medallion struck for the 1893 Chicago World Exhibition. Dated November 8, 1892, the medallion depicts one-year-old Ruth between President-Elect and Mrs. Cleveland and bears the legend “Baby Ruth.” Many sources, including the current owner of the Baby Ruth brand, claim that the original Baby Ruth candy bar trademark is patterned exactly after the engraved lettering of the medallion. If true, pro-Ruth Cleveland advocates could point to at least one piece of tangible evidence supporting the company’s alleged inspiration for the name.

But tangible evidence is too much to ask for in the Baby Ruth debate. It does not take a typography expert to observe that the legend on the medallion looks nothing like the legend on the original trademark. Moreover, the two typefaces are not even in the same family; the medallion “Baby Ruth” being sans serif while the trademark “Baby Ruth” is a serif typeface, the difference being that the sans serif typeface lacks the embellishments at the head and foot of each letter. In the world of typography, the two styles are as far from identical as a baseball and bat.

The Fame Index – Babe Ruth

It would take some doing to be more famous than Babe Ruth was in the 1920s; his profile can only be compared to mega-stars like Muhammad Ali and Michael Jordan. But it is imperative to focus on his fame when the candy bar was named, and, unfortunately, participants in the Baby Ruth debate have been sloppy in selecting the appropriate date for this measurement. Curtiss Candy contributes to this confusion by providing inconsistent dates for the initial release of the candy bar. The confusion has led to the oft-repeated hyperbole that in 1921 Babe Ruth was the subject of more newspaper coverage than President Harding, a revelation that is titillating, but also irrelevant and untrue.

Curtiss Candy has cited both 1919 and 1921 as the year the Baby Ruth was first introduced. Each date is supported by either certified documents submitted to the government or in sworn court testimony. In his sworn deposition from the trademark litigation, Otto Schnering testified that he first made and sold the Baby Ruth candy bar in November 1919. Other documents from that litigation consistently cite 1919 as the year Curtiss Candy first began using the notation “Baby Ruth.” To the contrary, the company’s 1924 trademark application attests that November 1921 was the date it first used the mark “Baby Ruth” in commerce.

The company’s conflicting statements cannot be reconciled, although a cynic might suspect that Schnering’s allegation of the earlier date in his deposition was intended to enhance the company’s argument that the Babe was not famous at the time. I cannot conceive that Schnering would risk perjury in order to bolster an argument that was not legally relevant to his case. If Babe Ruth was infringing on the company’s trademark, it did not matter whether the words “Baby Ruth” had been in use since 1919 or 1921. For that reason, and to continue the practice of allowing Otto Schnering, the underdog in this dispute, every opportunity to prove his case, I accept November 1919 as the date the candy bar was first launched.

Moving the point of reference from 1921 to 1919 creates problems for the pro-Babe Ruth faction. The Babe obliterated the home run record with fifty-four for the Yankees in 1920, and then hit fifty-nine in 1921. By the end of the 1921 season, he was truly the “Bambino.” A 2006 New York Times article probing the Baby Ruth debate proclaims that the Babe hit 54 home runs “the year before the first Baby Ruth was devoured.” That line of reasoning fails if the first Baby Ruth was devoured two years earlier, in 1919. Otto Schnering was no soothsayer. He could not have known in 1919 what the Babe would do in 1920 and 1921.

On the other hand, in November 1919 Babe Ruth was a prominent member of a Red Sox team that had won three American League pennants and three World Series titles in the previous five years. Our informal “fame index” for the Babe focuses on the Chicago Tribune and the Los Angeles Times, two papers with readily available online archives. My “fame” research compared the number of articles containing the Babe’s name against articles mentioning other leading sports figures. Advertisements, lists, and box scores were not included. The results were consistent between the two papers. Boxer Jack Dempsey far outstripped other sports figures in articles published from January through December 1919. But no other sports figure equaled the Babe’s numbers. His coverage in these two newspapers far eclipsed that of 1919 Triple Crown winner, Sir Barton. Among baseball players, articles mentioning Babe Ruth easily surpassed the number of articles mentioning future Hall-of-Famers Ty Cobb, George Sisler, and Rogers Hornsby – combined. With the exception of Chicago home town hero (and soon to be disgraced) Shoeless Joe Jackson, no baseball player came close to matching the coverage devoted to the twenty-four-year-old Babe in these two newspapers.

Two articles are particularly instructive as to the Babe’s popularity. The Los Angeles Times reported on October 25, 1919, that the Babe had quit the Red Sox to “enter the motion picture game.” And in an article slightly outside the sample period (published on January 8, 1920), the Los Angeles Times reported on the “rumpus” in Boston caused when Ruth’s sale to the Yankees was announced at a local boxing exhibition. A companion article offered that the Boston press corps was 100% behind management, decrying the Babe’s attitude as “too independent and childish, if not swell-head.” Without discounting the Hollywood angle for the first article, I find it telling that either of these incidents was deemed newsworthy in California - a state with no major league professional baseball.

Even using the benchmark year most favorable to Curtiss Candy - 1919, I believe it impossible that Otto Schnering or any other decision maker at Curtiss Candy was unaware of Babe Ruth’s fame when they named the Baby Ruth candy bar. The company’s contention that it would be years before the Babe would be famous is just not supported by the facts. While it is true that the Babe’s popularity would soon explode exponentially, by 1919 he was arguably the most publicized player in baseball. I do not believe it possible that Otto Schnering, a twenty-seven-year-old budding marketing genius with tremendous insight into what made America tick, was unfamiliar with the extent of the Babe’s appeal in American society at the time.

Was the Baby Ruth candy bar named after Babe Ruth?

In my opinion, these facts constitute an iron-clad case that: (1) Babe Ruth was a nationally famous figure in November 1919; and (2) Otto Schnering must have been aware of the Babe’s fame in November 1919. It reasonably follows that Schnering must have been aware that associating his new product with Babe Ruth would enhance sales. Of course, the evidence supporting these conclusions is stronger if the candy bar was not introduced until November 1921.

But it would be so much more satisfying to have a Colonel Nathan Jessep moment from A Few Good Men – “You’re damned right I ordered the Code Red!” If Otto Schnering could be confronted with the evidence at hand, he might simply respond – “Maybe you are right that Babe Ruth was very popular at the time, but his name never entered the discussion. I adored the memory of Baby Ruth Cleveland and I named the candy bar after her.”

While my research did not uncover a dead-on Colonel Jessep moment, it did turn up a bit of drama that comes about as close as it gets outside of Hollywood.

Tracking the trademark litigation case record to the office of the Clerk for the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Washington D.C., I discovered that it contains the transcript of a deposition given by Otto Schnering. I was surprised to learn that the clerk had only the original file, perhaps meaning that there had never been an occasion to copy the record to microfilm, microfiche, or other format. Unless someone had reviewed these documents in person at the clerk’s office, it appeared that no one had looked at the records in a very long time – perhaps not since the litigation ended in 1931.

Though intrigued, I did not expect the record to contain anything useful to my quest. The litigation involved Curtiss Candy’s claim against the Babe's candy bar, and the court’s 1931 published opinion made it clear that the naming of the Baby Ruth candy bar was not legally relevant. Curtiss Candy had registered its trademark for the words “Baby Ruth” in 1924 and had spent millions of dollars making Baby Ruth the best selling candy bar in the country, with sales reaching $1,000,000 a month by 1930. The legal issue in the litigation was whether Babe Ruth’s application to register the mark “Ruth’s Home Run” would cause confusion and enable Babe Ruth’s candy bar to benefit unfairly from the good will, reputation, and publicity generated by Curtiss Candy’s money and labor.

Babe Ruth’s best chance to prevail back in 1931 depended on the “unclean hands” doctrine which his attorneys raised late in the litigation. A successful “unclean hands” defense might have precluded Curtiss Candy from enforcing its otherwise valid trademark because it had obtained the mark by misappropriating Babe Ruth’s name. An appealing possibility, but I held little hope of finding anything helpful in the record. The court’s published opinion had brushed aside the suggestion of “unclean hands” because it had not been raised by Babe's attorneys in response to Curtiss Candy’s original objection to the Babe’s trademark application. Further, the court had determined that unclean hands could not be considered in this type of trademark proceeding, even if it had been properly asserted.

Therefore I was unprepared for an exchange at the conclusion of Otto Schnering’s deposition, when Schnering's own attorney asked him: "When you adopted the trade mark Baby Ruth in 1919, did you at that time taken [sic] into consideration any value that the nickname Babe Ruth for George Herman Babe Ruth might have?"

Ladies and Gentlemen - Colonel Jessep has entered the building!

Babe Ruth's counsel then interjected: "Note on the record that witness remains silent for some minutes – for upward of two minutes before answering. When such objection is raised witness states that he is thinking so as to give a very clear answer to the question."

(I want the Truth!)

Otto Schnering finally replied: "I could have answered that question very quickly. The bar was named for Baby Ruth, the first baby of the White House, Cleveland, dating back to the Cleveland administration."

(You can't handle the Truth!)

But Schnering continued: "There was a suggestion, at the time, that Babe Ruth, however not a big figure at the time as he later developed to be, might have possibilities of developing in such a way as to help our merchandising of our bar Baby Ruth."

There it was - in a deposition transcript that had been gathering dust for eighty years. Curtiss Candy considered the connection between the name Baby Ruth and the baseball player Babe Ruth at the time the candy bar was named. Further, Curtiss Candy considered the potential impact of the name similarity on marketing. Schnering’s facile contention that Babe Ruth was "not a big figure at the time" is contradicted by our Fame Index. And even if we were to credit Schnering's contention to the contrary, the Babe was famous enough for the company to know about him and consider the merchandising implications of the similarity between the two names.

Babe Ruth and Baby Ruth Today

The Curtiss Candy Company and its successors have taken advantage of the link between Babe Ruth and the candy bar for ninety years. Most notoriously, the company erected a large Baby Ruth billboard at Chicago’s Wrigley Field, strategically placed near the spot where the Babe’s legendary “called shot” home run landed in the 1932 World Series.

The Baby Ruth brand passed from Curtiss Candy to Standard Brands to Nabisco to the Swiss company Nestlé. Nestlé and Babe Ruth’s estate kissed and made up in 1995 when the company contracted with Babe's heirs to use his image and likeness to market Baby Ruth. In 2006, Baby Ruth was named the official candy bar of Major League baseball. Like the belated legitimatization of a common law relationship, the link between Babe Ruth and Baby Ruth has been officially blessed, albeit without any admission of paternity.

Conclusion

Josephine Tey’s classic mystery, The Daughter of Time, evokes the proverb that “truth is the daughter of time.” While often interpreted to mean that the perspective gained through the passage of time leads to “truth,” I suspect Tey meant exactly the opposite. Her modern day protagonist’s struggle to solve England’s medieval murder of the “little princes” demonstrates that the passage of time can distort truth. Shakespeare’s biased (yet politically expedient) account of the murders in Richard III has become, over time, the “truth” against which Tey’s protagonist wrestles throughout the novel.

Like Tey’s Inspector Grant, I have attempted to banish temporal distortion from this examination of the Baby Ruth debate. The pro-Ruth Cleveland argument has long benefited from the maxim that history is written by the victors, with an assist here from a court decision obliquely supporting Curtiss Candy’s version of the truth. The pro-Babe Ruth faction, on the other hand, has often overstated its case by inserting the anachronous Babe Ruth of 1921, 1924, or 1929 into the debate. Just as our modern image of the Babe is distorted by those grainy motion pictures of the overweight Bambino shuffling around the bases on comically quick legs, the passage of time makes it difficult to separate the young Babe from the more familiar bigger-than-life character he became.

Even after deflating the Babe back to the twenty-four-year-old, pre-Yankee, pre-icon version, and granting the talented Otto Schnering the benefit of every doubt, I conclude that the Curtiss Candy Company chose the name Baby Ruth for its new candy bar fully conscious that the young Babe Ruth was among the most popular sports figures in America at the time, with the intent of benefiting from consumers’ inevitable association of the candy bar with the ball player. The role of Ruth Cleveland was, at best, a convenient pretext; at worst, an after-the-fact fabrication.

Post Script

On a lighter note, and I think you’ll find this absolutely fascinating – Did you know that the "Oh Henry!" candy bar is not named after the famous short story writer O. Henry?

October 2011

From guest contributor Patrick O'Hara |