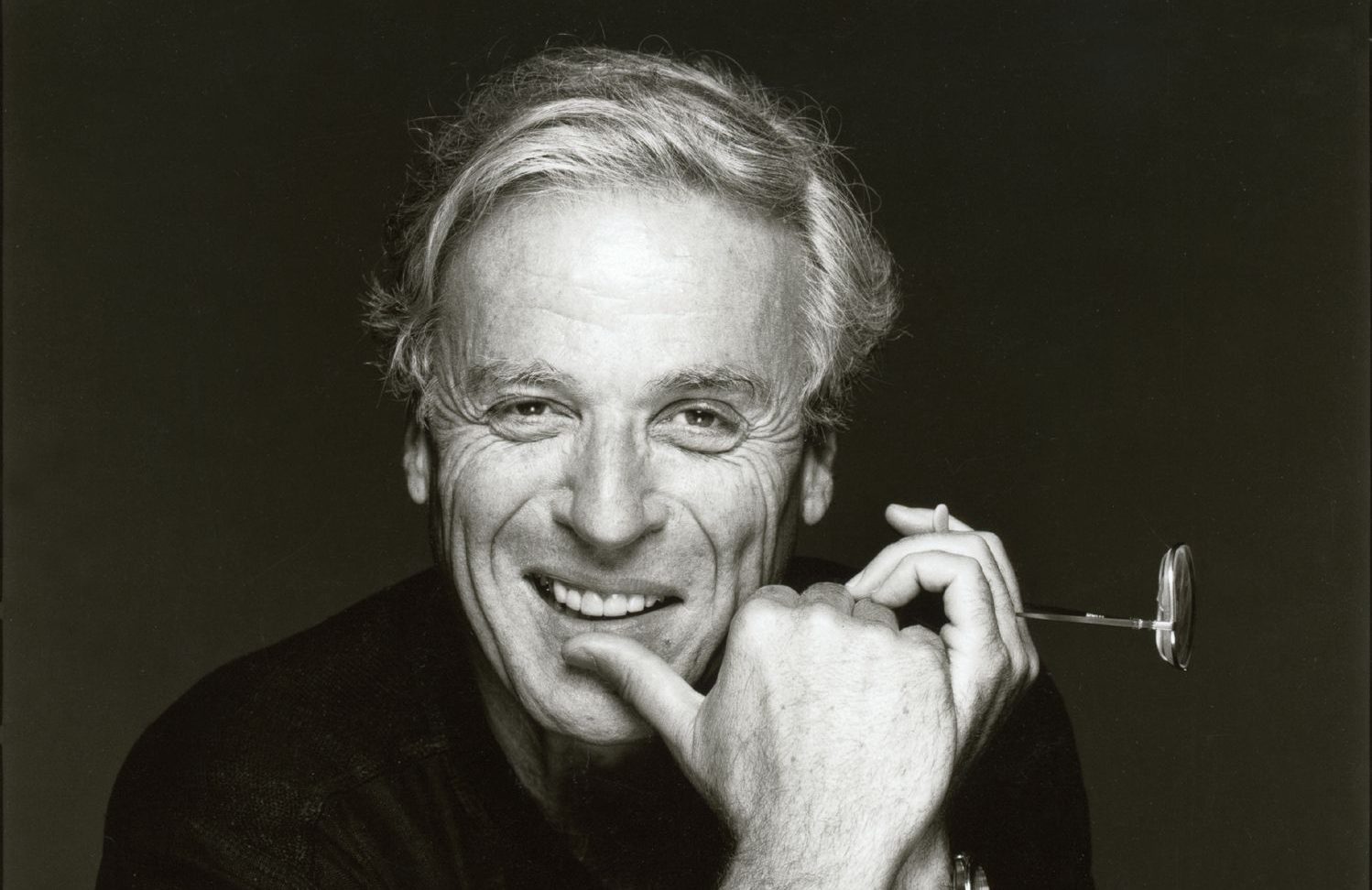

Enigmatic, elusive, and impossible to categorize, William Goldman was the most influential writer in Hollywood during the second half of the twentieth century. With thirty-three produced screenplays to his credit, two Academy Awards, and countless scripts that he is rumored to have doctored or directly influenced, there is no doubt of his place in screenwriting history. Throughout his life and career, however, Goldman remained an outlier – breaking rules, bucking trends, and constantly flying in the face of the Hollywood norm. To truly understand the author's unique makeup, one need only listen to his own words, and there are many of them. Variety highlights a phrase that Peter Debruge suggests those working in the business should get "tattooed on…[their] forearm." What words did Goldman choose to sum up his impression of Hollywood?

"Nobody knows anything."

It is this brash and bristly persona that Goldman would become known for. However, a closer examination of the man, the artist, and his pathway to fame reveals another side to this literary icon, composed of the very same characteristics that he imbued his characters with. This elusive dimension of his personality was far less guarded, more honest, self-deprecating, humorous, vulnerable, self-loathing, and, above all, heartfelt. When viewing his life through his own words, we discover an unconventional approach to Hollywood that was integral to his success. William Goldman is one of Hollywood's unlikeliest success stories, who blazed his own path by willfully disregarding the unspoken rules of the industry, following a counterintuitive career trajectory, and writing wildly successful screenplays that rebelled against conformity.

"I don't like to be around the set...It's not a great pleasure for me to be there. It's so f------ boring, and I get in the way," recalled Goldman in a 2009 interview with Joe Queenan. One of Hollywood's most revered and successful screenwriters, Goldman is also one of its greatest critics, adding to the improbability of his career rise. In Tinsel Town, where the norm is a sense of desperation with every actor, writer, director, or crew member angling to log as much on-set time as possible, Goldman refused to play the game, valuing product over process. Queenan noted that "the magic of movie-making…seems lost on him." Goldman recounted to Queenan his anxiety while filming The Princess Bride, saying, "I was on the set and I moved out of the way of a shot just as Rob Reiner was ready to say, 'Rolling!' Suddenly he stopped and said, 'Bill, that's where we're going to move the camera." For Goldman, being on the set was pointless and asinine, as were the absurd hierarchy and inherited mandates of Hollywood.

Goldman defied authority at every turn in his professional career, and his audacity is even more apparent in the way that he chose to relate (or not) with Hollywood. The author seemed unable to resist the lighthearted jab against the system. In her article for the Chicage Tribune, Cheryl Lavin explained that he tried, whenever possible, to deliver his first drafts on April Fool's Day and relentlessly poked fun at the very industry that provided his livelihood, his fame, and his greatest successes. He believed that no one, including critics, had the least idea of what was going to succeed.

While his contemporaries lived in fear of the power that movie critics and film historians wielded, Queenan recalled that Goldman openly referred to them as "failures and whores." Never one to cower or cater to the whims of studio executives, directors, and stars, the author seemed to view them as obstacles standing in the way of a story desperate to be liberated. Scott Myers, in his 2018 article for Into the Story, recalled of Goldman, "He did not suffer fools gladly. I remember going into a meeting at Warner Bros. in which the execs were all atwitter about something that had happened earlier that day. Goldman had been hired to adapt the novel 'Memoirs of an Invisible Man,' a project to which Chevy Chase was attached to star when Chevy Chase was CHEVY CHASE in terms of his box office appeal. It was a high profile gig. Goldman, who lived in New York City and hated L.A., flew out to The Coast for a notes meeting on the script he had delivered. The meeting included studio executives, producers, and Chevy Chase himself. They provided script note after script note after script note, and at the end, Goldman simply stood up and reportedly proclaimed, 'F--- it. I make too much money to deal with this shit,' and walked out of the meeting."

In Hollywood, where youth is king, Goldman clearly articulated that his respect was reserved for those with proven longevity. To make a film was easy. To maintain that success and build upon it shows an artistry of a higher caliber. His appreciation of Clint Eastwood, who, like him, was born in the early 1930s, is well-documented, particularly in relation to directing, which Goldman loathed. "[I] would rather die than direct. I wouldn't know what the f--- to say to an actor," Goldman said in a 2013 interview with Christopher Boone. Eastwood, however, and others, trudged through Hollywood for many years without losing their innate artistic identity. Goldman knew struggle, and knew how difficult it was to hold on to that part of you that produces something beautiful while the outside world attacks you with the slings and arrows of career climbing, one-upmanship, and the fleeting nature of fame in Hollywood. "Directors lose it around age 60," said Goldman in his interview with Queenan. "They're either too rich or they can't get work anymore. And it's physically debilitating work. That's why Gran Torino amazes me. Clint Eastwood is 78 and he can still make a movie like that."

Similarly, Goldman lavished his uncommon praise on Laurence Olivier. Perhaps the greatest living actor at the time, Olivier was shooting a scene for Marathon Man with Dustin Hoffman, who was notoriously hard to work with. As the aged Olivier rehearsed the scene, walking back and forth with swollen ankles and considerable difficulty, the much younger Hoffman took his time. After more than an hour, Olivier refused to say he needed a break. Goldman noted to Queenan, "Olivier wasn't going to give in…Because he was Olivier." Goldman wasn't the kind to give in, either. His career had not been a traditional one, and he understood the grit, determination, and fortitude that it took to survive in Hollywood without losing yourself.

"Some authors start out, no doubt, knowing they want to write screenplays. I am basically a novelist, and I fell into screenplay writing rather by misinterpretation," stated Goldman in The Movie Business Book. Goldman's flight plan to Hollywood screenwriter extraordinaire had been unconventional. His success grew from humble beginnings, recalled Sean Egan in his article, William Goldman: the Reluctant Storyteller. The son of an alcoholic father who committed suicide, Goldman knew the difficulties of the common man. His mother had struggled with deafness, and Goldman's earliest writing attempts had met with harsh criticism in school. During his 2009 interview with Queenan for The Guardian, the author described his time at Oberlin College where he graduated with a degree in English and served as the editor of the school's literary magazine. Goldman said, "I was so programmed to fail…I had shown no signs of talent as a young man." He went on to say that he would submit his short stories anonymously for the magazine, all of which were unanimously rejected. He enrolled in a creative writing course to strengthen his writing, and found himself once again at the bottom of the pile. Commenting on those dark times later, Goldman lamented, "Do you know what it's like to want to be a writer and get the worst grades in the class? It's terrible."

Goldman's prospects improved upon earning his master's degree from Columbia in 1956. Still, he was filled with trepidation. Motivated by the intense fear of spending his career as a copywriter at an ad agency, Goldman penned his first novel, The Temple of Gold, in under three weeks. Those early days as a novelist would remain forever at his core, as his obituary in The Irish Times explained, "he considered himself not a screenwriter but a novelist who wrote screenplays." In his groundbreaking Adventures in the Screen Trade, Goldman explained that the world of film arrived while he struggled with the manuscript for Boys and Girls Together. To clear his head, he wrote a short novel in ten days called No Way to Treat a Lady, which ended up in the hands of a well-known actor, Cliff Robertson. Sometime later, Goldman was contacted by Robertson, who had assumed that the short work was a screen treatment rather than a novel. Robertson asked Goldman to write an adaptation for him of Flowers for Algernon. After agreeing, Goldman realized that he had no idea how to write a screenplay and had never even seen one. Panicked, he ran out at 2am to an all-night bookstore in Times Square and bought the only screenwriting book available. His relationship with Robertson was a failure and the project, for Goldman, was a disaster. However, this first foray into screenwriting would lay the foundation for what was to come.

After firing Goldman, Robertson finished the project and went on to win Best Actor without Goldman's involvement. While losing out on an Oscar-winning adaptation job would crush most careers, Goldman was able to use it as a springboard. He had spent time on set with Robertson and learned a number of lessons that would stay with him for the rest of his life. Above all, he had been introduced to the business end of "the business." Goldman became acutely aware that the bottom line would never be sacrificed in the interest of artistry. It was a formative lesson for the author, and one that would lead to his eventual breakthrough with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

By 1967, says Lavin, the 36-year-old's career was in flux, but he had made some inroads in Hollywood. He had also developed the hard exterior that would become his calling card. After a few minor triumphs, Goldman's career-making hit came in the form of a film that ostensibly invented the cowboy buddy genre, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. At the script's first auction, every studio passed except for one, which requested a significant change to the script. According to his 2010 interview with Christopher Boone for Writers Guild Foundation, Goldman stuck to his guns and did a small rewrite instead, changing other elements to make the script more palatable, and a bidding war ensued. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid eventually sold for a record-setting $400,000 to 20th Century Fox. In what Goldman called a "brilliant piece of agenting," the relatively unknown writer found himself on the front page of every newspaper in Los Angeles.

Despite his success, however, Goldman resisted the allure of Hollywood’s gilded cage, choosing instead to live with his wife in New York, which was virtually unheard of for a screenwriter at the time. Discussing his refusal to live on the West Coast with Daniel Argent in their 2015 interview, Goldman said, "I think one of the reasons that I've survived is that I've lived in New York. No one gives a shit in New York; in LA, it's such an obsessive place in terms of who's in and who's out and who's hot and who's cold." The decade following brought a string of successes: The Stepford Wives, All the President's Men, Marathon Man, and A Bridge Too Far. But the Eastwoods, Oliviers, and Goldmans of the world must suffer hard times as well to earn their unconventionality. From 1980-1985, Goldman saw the other side. He told Argent, "I was a leper…I had the five years…when the phone didn't ring. And that will happen again. It happens to everybody."

No one had seen a career like this in movie-making. William Goldman was supposed to be finished, but his focus was bigger than Hollywood, bigger than screenwriting. He was going to continue to tell stories the way he wanted to tell them. Goldman wrote as a novelist, he wrote fiction and nonfiction, and every word he penned influenced the next generation. His reach was undeniable, regardless of genre. Aaron Sorkin, one of the many writers mentored by Goldman, authored a piece for the Los Angeles Times entitled "Aaron Sorkin remembers William Goldman: 'He was the dean of American screenwriters and still is.'" In discussing the rich literary heritage established by Goldman, Sorkin effused, "as good a screenwriter as Bill was — and I think he's the best who's ever lived — he was an even better novelist. And as good a novelist as he was, I think he was an even better writer of nonfiction...Adventures in the Screen Trade is an indispensable and hilarious look at Hollywood, and you won’t be able to put it down. Are you a fan of Broadway? Read The Season. You're a sports fan? Go to Amazon right now and order a book Bill tandem-wrote with Mike Lupica called Wait 'Till Next Year, which examines the 1986 New York Mets and New York Giants as they both try to repeat as world champions."

Goldman defied categorization, which would be a key component of his screenplays as well. His scripts ranged from westerns, to psychological thrillers, to dramas, to dark comedies, to action movies, to war pieces, to period pieces, and everything in between. While most of those around him bent to the will of the Hollywood machine, Goldman made certain that his scripts would be his most prominent middle finger to the industry and its expectations. "They're all really smart people, and they all know that they're going to get fired…And when they get fired, they can't get a good seat in their favourite restaurant," Goldman told Queenan. While delivering his blunt assessment with biting wit, Goldman did, at times, show empathy for those in his industry. At heart, however, he remained a renegade, refusing to bend his artistic vision to fit in what he saw as the warped world of Hollywood.

Goldman continued to reject the Hollywood standard in every way, and his successes only hardened his resolve. Queenan noted that "he knows that stars dominate the industry, but has not been the least bit reluctant to disparage them. He has often been disappointed by the craven stupidity of studio executives, but retains an odd compassion for them." Goldman knew he could do things his way, provided that he made money for the studios. Hollywood was a wide open frontier to him, and he intended to make the most of it, on his own terms, as he outlined in The Movie Business Book, saying, "It is a golden time to write screenplays. It's a whole new and unpredictable ballgame. Now one can write anything. Since no one knows any more what will or won't go, almost anything has a chance of getting made. Now it seems possible for a writer to say what he wants through film and make a living at it."

Goldman was an architect, and like a brick-layer, he knew how to construct a story – any story. After the release of the drama-thriller Heat in 1986, Peter Debruge noted in his article for Variety, the following year saw a complete about-face with the universally praised romantic comedy The Princess Bride, based on Goldman's own novel as well. Goldman explained in his interview with Boone, "Screenplays are structure. Story is everything." However, unlike writing a novel, Goldman saw that movie-making was a team effort, a collaboration of craftsmen, each with their own contribution to the cooperative effort, and a screenwriter was only one part. Perhaps this is why Goldman felt so free to do his part in a way that was as unconventional as he was.

William Godman's approach to formatting a screenplay was emblematic of his approach to Hollywood. While he admitted that certain criteria must be adhered to, he said to Argent, "when you decide to do a movie about something, there's something in it that moves you. Whatever that is, you'd better protect that." The eccentric author refused to follow traditional screenwriting format. Still, the successes rolled in. During the last decade of the twentieth century, he composed Memoirs of an Invisible Man, Misery, Chaplin, and Absolute Power, and contributed to multiple Oscar-winning projects, says Brian Tallerico in his article, "William Goldman: 1931-2018: Balder and Dash: Roger Ebert."

In Adventures in the Screen Trade, describing his reaction to seeing his first screenplay, Goldman wrote, "To this day I remember staring at the page in shock. I didn't know what it was exactly I was looking at, but I knew I could never write in that form, in that language." To further illustrate his point, he provided a sample adaptation of the famous T-shirt scene from The Great Gatsby in standard screenwriting format. He concluded, "This scene from the novel…is one of the most moving in a desperately moving book…Not only is this one of the high points of the book, it works on film. It worked in the recent version when Redford played the title role. My God, it even worked with Alan Ladd in the lead. But it sure doesn't work here. Why? Because the form of the screenplay is basically unreadable. Everything brings your eye up short. All those numbers on both sides of the page and those Christ-awful abbreviations and the INT.'s and the EXT.'s and on and on."

Expounding further, he said that the format itself halts the eye, providing necessary indicators for schedulers, production designers, and wardrobe, but which take away from the intention of the story being told. Further, in The Movie Business Book, Goldman unequivocally stated, "The style is impossible and must be dispensed with…Instead, I use run-on sentences. I use the phrase cut to the way I use said in a novel – strictly for rhythm. And I am perfectly willing to let one sentence fill a whole page. Here's an example from the ending of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid:

CUT TO:

BUTCH

He has the ammunition now and --

CUT TO:

ANOTHER POLICEMAN

screaming as he falls and --

CUT TO:

BUTCH

his arms loaded, tearing away from the mules and they're still not even coming close to him as they fire and the mules are behind him now as he runs and cuts and cuts again, going full out and

CUT TO:

THE HEAD POLICEMAN

cursing incoherently at what is happening and --

CUT TO:

SUNDANCE

whirling faster than ever and --

CUT TO:

BUTCH

dodging and cutting and as a pattern of bullets rips into his body he somersaults and lies there, pouring blood and --

CUT TO:

SUNDANCE

running toward him and --

CUT TO:

ALL THE POLICEMEN

rising up behind the wall now, firing, and --

CUT TO:

SUNDANCE

as he falls.

Goldman explained, "In this sequence, I've used the proper form, but I never want to let the reader's eye go – it's all one sentence." Indicative of both his refusal to conform and fondness for the unconventional, this writing style would have been rejected out of hand, had it not been for the author's storytelling ability. He would frequently submit 400-page scripts and refuse the notes of studio execs. In Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, he ignored the basic three act structure and divided the film into two halves. Glenn McDonald, in his article for PopMatters, notes that in addition, he included a 24-minute chase scene with virtually no dialogue. In All the President's Men, Debruge observed, there is very little action. It relies instead on process-oriented shots like typing, phone calls, and knocking on doors, yet still it was one of the most engaging and influential films of its time.

Goldman's narrative style and lighthearted, authentic communication made him a standout, regardless of formatting. He allowed no pretense to intrude upon his story or its characters. He quite literally invented a new form of dialogue. Debruge, in his article for Variety, stated, "Long before Quentin Tarantino elevated the act of talking around a thing into being more pleasurable than the thing itself, Goldman had perfected the art of banter." His dialogue was like no one else's. Take for instance, the sword fight between Inigo and the Man in Black in The Princess Bride. Goldman cheekily writes:

INIGO. Who are you?!

MAN IN BLACK. No one of consequence.

INIGO. I must know.

MAN IN BLACK. Get used to disappointment.

INIGO. Okay.

Following in his stead, a new generation of writers were free to make use of this verbal sparring. In addition to Sorkin, Matt Damon, Ben Affleck, Scott Frank, and Tony Gilroy were all mentored by the screenwriting legend, Sorkin writes, "He once called me up to apologize. 'I'm mortified,' he said. 'Why? What happened?' I asked. 'In a story in today's Hollywood Reporter,' he replied, 'the guy says I had a hand in writing A Few Good Men. I called the editor and set him straight.' I wasn't mortified at all. Someone had mistaken something I had written for something William Goldman might have written. I wanted that at the top of my resume."

Beyond the characteristically untraditional formatting and narrative style implemented in Goldman's work, one must consider the impact made on the film industry that stemmed from his choice of content. While he shunned being on set, and certainly had no love of directing, his screenplays themselves served as a kind of blueprint for directors in an unprecedented way. While humor had been established in the western genre, there were certain unspoken rules of dialogue that remained unquestioned…until Godman. While a funny sidekick often made his way into John Ford's films, the steely-eyed protagonist was usually presented as a world-weary man who demanded the respect of those on both sides of the law. In Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, however, Goldman presented a complete departure from the heroic cowboys and deadly fugitives from justice so common to the genre. Instead, he embraced the story of two bank robbers running from the law, waffling between their criminal past and the novelty of "going straight," all the while cracking jokes at the unlikeliest moments and providing levity at the very point that most screenwriters seek to enhance the dramatic pretense. In Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, a faceoff between Butch and Logan highlights the humor that Butch finds even as he faces possible death:

LOGAN. Sundance – when we’re done, if he’s dead, you’re welcome to stay.

CUT TO

BUTCH AND SUNDANCE looking out at Logan. Butch speaks quietly to Sundance.

BUTCH. Listen, I’m not a sore loser or anything, but when we’re done, if I’m dead, kill him.

SUNDANCE. (This is said to Logan, but in answer to Butch.) Love to.

In this brief interchange, in dialogue that would never have been uttered by John Wayne, Goldman firmly establishes an entirely new approach to the western genre. The looming confrontation is not satire, nor is it tongue in cheek. The ensuing fight delivers the promised action-packed and danger-ridden fistfight, but also shows the complexity of characters who find humor and even joy in the moments that audiences had come to expect, which would become a hallmark of Goldman's writing, to break the unwritten rule and unearth a deeper level of character. In All the President's Men, Bradlee succinctly utters the line, "We're under a lot of pressure, you know, and you put us there – nothing's riding on this except the First Amendment of the Constitution, freedom of the press and maybe the future of the country. Not that any of that matters, but if you guys f--- up again I'm going to get mad." There is no Capra-esque focus on the greater good here, no Mr. Smith Goes to Washington altruistic sacrifice, but a modern galvanization of social justice and hubris. Decades earlier, acknowledging a character's motivation to be both selfish and righteous was all but nonexistent. By weaving this authenticity into the fabric of his characters, by not aligning with the values set forth by his predecessors, Goldman refuted the previous assumptions about plot development and characterizations and raised the standard for all those who would come to stand in his shadow.

In the final years of his life, Goldman bemoaned what it was to be a screenwriter, saying in his interview with Argent, "the whole thing is building up confidence that it's not going to stink this time. If you decide you want to write, you magically have people in your head that drove you toward that life decision, to whatever you read when you were a kid, or whoever you saw when you were a kid. And you know you're not that good. You realize you're not going to be Chekhov, you're not going to be Cervantes, you're not going to be Irwin Shaw, who is the crucial figure for me. And so you go into your pit alone, hoping, trying to fake yourself out that this time you will be wonderful. And that's hard."

A career path is forged, not followed. No one knew that better than Goldman. In forging his own path, he forever changed the landscape of film. Goldman dwelt in his pit alone. He separated himself from all others by breaking long-held industry rules, building a career that seemed "inconceivable," and crafting irresistible stories that were rebellious in every way. Yet always, there was the pit. There was the darkness of his past, the dankness of a Hollywood machine that he saw as soul-crushing, and the mildew-infested guilt he clung to for succeeding so wildly in a career he despised. Still, this is not his legacy, but a way to operate without losing his artistic center. That is, after all, what every writer must do. They must, as Steve Martin says, "be so good they can't ignore you," and William Goldman was that good. He was so adept at telling a story that you simply couldn't turn away. Perhaps this is why Sean Egan heralded him as one of the late twentieth century's most popular storytellers.

For Goldman, though, popularity was never the goal. The goal was to live on the knife's edge between misanthropic artist in exile and generational influencer, penning stories like no other. He illuminated this paradox in his own singular way to Argent, saying, "It's an odd life. It's not a good life. It's been wonderful for me, but I don't recommend it as a way of getting through the world. It's weird! You intentionally closet yourself from everybody else, go into a room and deal with something no one gives a shit about until it's done."

The world may remember him for his defiant success and his affinity for the inflammatory. William Goldman's true legacy, however, is in the simple wisdom of his own words within The Movie Business Book, that all writers should tattoo not on their forearms, but deep inside their very being: "there are no unbreakable rules."

March 2020

From guest contributor A. D. Hasselbring, Pepperdine University |