The Archetypal Action Hero |

According to Chris Palmer, the essence of cultural collusion

is “intuitive coincidence”; contemporary popular

culture, independently of earlier, canonical sources, recreates

the trends, popular symbols, or thematic systems prevalent

in the popular cultures of earlier societies. This intersection,

following Palmer, “says interesting things about the

connection between our moment” and those moments that

preceded, not only demonstrating a similarity in the cultural

conditions that lead to the creation of the earlier text,

but also saying “something quite telling about our present

condition.”

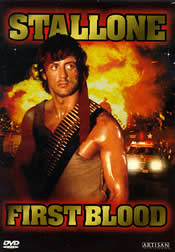

Perhaps there is no more typified representation of American

popular culture than action films, a genre largely noted for

its classic though incessant repetition of tone and mundanity

of story. Action movies are often relegated to an inferior

status; “dumb movies for dumb people,” as Yvonne

Tasker calls them. Though it is certainly true that these

movies often lack in plot, character development, and an overall

story line, action movies do offer a fascinating glimpse into

the world of masculinity by demonstrating an exaggerated and

overstated sense of what it means to be a “real man”

through the gaze of American cultural standards. These films

“perform” the masculine, developing scenarios in

which an ordinary individual is transformed into a muscle-bound

superhero who single-handedly rights wrongs, saves the day,

and in general glorifies the male body (demonstrated through

an enlarged musculature and stimulated libido), persona (often

displayed through flashes of caustic wit utilized in highly

inappropriate moments, thus demonstrating an extreme sense

of coolness under fire), and sense of honor (shown when the

hero refuses to “sink to the level” of the villain,

though the villain is often conveniently destroyed in the

end of the film anyway, allowing the hero an honorable scene

of destruction). Designed specifically to exploit and explore

exaggerated male social constructions, action heroes, according

to Barbara Creed, represent “an anthropomorphised phallus,

a phallus with muscles, if you like... they are simulacra

of an exaggerated personality, the original [concept of masculinity]

completely lost to sight, a casualty of the paternal signifier

and the current crisis in master narratives.”

The archetypal action film works, for the most part, on the

following precept: an individual, a lone male, sometimes accompanied

by family or significant other, seeks isolation and retirement

from an occupation or society that often forces him to assert

his already overdeveloped masculinity. This man may perhaps

be a retired or vacationing soldier, police officer, government

agent, or something similar, a real “man’s man”

who, for the moment, is trying to disenfranchise himself from

the society that he did not create but often attempts to control

by retreating into a paradise of some kind, an Eden offering

him shelter and, more importantly, tranquility. Something

intercedes—perhaps an old enemy, or simply an irrevocable

situation in which our hero finds himself. Suddenly, chaos

reigns, and our hero is the only man capable of restoring

order to what was once paradise. Working against seemingly

insurmountable odds, through a hail of gunfire, countless

explosions, and innumerable hired thugs, our hero triumphs,

and order is restored to the world once again. Our hero is

then rewarded, either by being reunited with loved ones, or,

perhaps more commonly, with a kiss from the film’s love

interest, almost always on hand, the yin to our hero’s

yang, to remind him of his less violent side and of the existence

of a more feminized and less violent side of society as well.

This pithy but accurate description of action films and action

heroes, culled from dozens of such films, applies equally

well to a genre of literature that appears centuries before

the invention of such film. Viking saga literature features

situations and characters very similar to current American

action films. While this seems hardly surprising—the

outline is basic enough—it is interesting that almost

every aspect of the exaggerated masculine genre and caricature

is captured by another society also fascinated with masculinity.

Yet in the thirteenth-century Icelandic work Njal’s

Saga, the character of Kari Solmundarson capably represents

the archetype of the action hero, redefining levels of masculinity

while performing the masculine in his attempts to gain revenge

for the burning of Njal, Njal’s family, and Kari’s

own son Thord.

How the archetype of American masculinity appears in this

work not only demonstrates similarities in the cultural identities

between the masculine standards of both cultures, but also

proffers an interesting view into the ideas of masculinity—and

its distortions—in both societies as well. Thus, here

we see cultural collusion at work—two similar tropes

being achieved independently of one another as a result of

identical or nearly identical cultural phenomenon affecting

the popular culture of the day. This is not to state that

the two creating cultures must be identical; rather, it indicates

that some aspect of the previous culture is independently

and of its own volition echoed in the latter, and this echo

results in cultural collusion. Thus, Kari is a thirteenth-century

equivalent to Arnold, Sly, and Jean-Claude, and while there

is no direct lineage between the two, they exist as cultural

simulacra representative of similar, transhistorical ideals

emerging from separate times and places.

In Njal’s Saga, Kari is the figure who best represents

cultural collusion, as both a creation of the representative

culture and an iconic mimic of today’s action hero. The

archetypal American action hero is not born; he must be created,

almost against his will, through a precise set of conditions

found in the society around him. This process is what will

ultimately separate Kari from the other characters in Njal’s

Saga and works to explain why he and only he represents

the archetypal action hero.

Kari first appears in the saga in blazing glory, sailing

in to save Njal’s sons Helgi and Grim from a marauding

band of Vikings. The anonymous author describes Kari as “a

man with a magnificent head of hair, who wore a silk tunic

and a gilded helmet and carried a spear inlaid with gold.”

This is a glorious description by the standards of the author

of Njal’s Saga, who often ignores personal detail

in favor of necessary descriptions of the complex but historically-based

plot. Kari is called “the stranger” by the narrator,

a tactic later mimicked by Clint Eastwood westerns; when he

sails in to save Helgi and Grim, he becomes a selfless warrior

risking his own life and ship for two people he does not know.

This good Samaritan scene lays the foundation for Kari’s

rise to archetypal masculinity; he is shown to be courageous,

feckless, and larger than life: in short, a hero. Though this

type of figure is not uncommon in Njal’s Saga

(several men fit the same description), it is important to

his development as action hero that Kari’s journey towards

archetype begin as simple hero; it is, after all, only the

good and brave man, such as the cop or the soldier, who can

be transformed into the exaggerated pattern of masculinity

prevalent in the sagas and the action film genre. Thus, step

number one in becoming an action trope—the establishment

of a solid system of values and almost foolish sense of bravery—is

achieved.

Kari is heartily accepted into his new family; he marries

Njal’s daughter, has children with her, and becomes a

surrogate son to Njal himself. This is step number two in

his transformation; a wandering stranger cannot become the

archetype action hero; he must be wedded to something—such

as the law—though, ideally, he should be a family man.

The presence of wife and child reaffirms the sense of normalcy

that the hero both fights for and longs to return to, as well

as stands to confirm his own potent sense of heterosexuality.

While an exaggerated masculinity is not often confused with

homosexuality, the male-dominated homosociality of the action

hero could potentially lead to “embarrassing questions.”

The hero must be viewed as an everyman, maintaining a wife,

kids, and the proverbial picket fence; he must be a man with

much to lose. Often, it is the threat of this loss (and in

some cases, the actual loss) of his family and his lifestyle

that will spurn the reluctant hero to action.

This loss translates into suffering, the key ingredient and

third step in the making of an action hero. As Tasker states,

“within this structure, suffering operates as both a

set of narrative hurdles to overcome, tests that the hero

must survive, and a set of aestheticized images to be lovingly

dwelt on. [Through this,] the hero is subjected to torture,

humiliation, and mockery at some level,” thus challenging,

and through overcoming this challenge, reaffirming the hero’s

masculinity. Kari’s suffering includes the burning of

his son, Thord, his father-in-law Njal, his brothers-in-law,

and the attempted burning of himself by Flosi. As with all

archetypal action heroes, the escape is close, and some physical

suffering, as well as psychological, must be endured: “Kari’s

clothes and hair were on fire by now, as he threw himself

down off the wall dodged away in the thick of the smoke.”

The escape is made, but it had been close, and the hero must

now carry the aesthetic evidence of his suffering wherever

he may go.

The creation of our hero is almost complete; a good man,

accepted into a surrogate family, has now suffered a great

and terrible loss; what must follow next is a great and terrible

reckoning. Revenge is a way of life in Njal’s Saga,

but Kari advances beyond the simple blood-feud; he desires

to “have his sword harden... in the blood of the Sigfussons

and the other Burners.” He will not accept any settlement,

though he encourages others to do so, to spare them the anguish

of what is to come. The path of the archetypal action hero

must be traversed alone; Kari rids himself of steady companionship

and seeks revenge on his own. He does not weep, he does not

lament; as he himself states, “there were more manly

things than weeping for the dead.”

These “manly things” consisted largely of lusting

for revenge. Kari’s existence is now defined largely

through the burning; to him, there is nothing else:

Sleep is denied my eyes

Throughout the night,

For I cannot forget

That great shield of a man;

Ever since the warriors

With the blazing swords

Burned Njal in his house,

I cannot forget my grief.

Kari’s life is no longer his own; his creation as archetypal

action hero is now complete. A man possessed, there remains

only one thing left to do.

In action, Kari is simply awe inspiring, performing deeds

no mortal man ever could:

Kari Solmundarson came face to face with Arni Kolsson and

Hallbjorn the Strong. The moment Hallbjorn saw Kari he struck

at him, aiming at the leg; Kari leapt high, and Hallbjorn

missed. Kari turned on Arni Kolsson and hacked at his shoulder,

cleaving shoulder-bone and collar-bone and splitting open

the chest. Arni fell down dead at once. Then Kari struck

at Hallbjorn; the blow sliced through his shield and cut

off Hallbjorn’s big toe. Then Holmstein Spak-Bersason

hurled a spear at Kari, but Kari caught it in mid-air and

returned it, killing a man in Flosi’s following.

Kari’s revenge is bloody and terrible, but just under

Icelandic law. The action hero may work outside of the law,

or the law may officially frown upon his actions, but he never

really breaks it. The law is powerless to stop him, though

it may wish to do so. In perhaps the most stark of all of

Kari’s revenge scenes, he “ran the length of the

hall and struck Gunnar Lambason on the beck with such violence

that his head flew off on to the table in front of the king

and the earls.” Sigurd, one of the aforementioned earls,

acting as an official of the law, orders Kari seized and put

to death. No one moves; no one pursues him. They stand in

awe; Flosi, head conspirator against Njal, defends Kari by

saying that “he only did what was his duty,” pointing

out that Kari had refused to accept a settlement and was thus

legally entitled to blood compensation. The earl himself is

amazed; “there is no one like Kari for courage,”

he finally notes.

Ultimately, Kari must conquer Flosi, the head of the Burners,

the equivalent to the mastermind villain in the saga. Flosi

is not an unremitting evil as villains tend to be in American

action films, but his actions are deplorable and acted under

tenuous motivation. He is powerful and well-protected, like

any villain surrounded by a cartel of thugs, and true to the

filmic formula, Kari eliminates Flosi’s henchmen and

co-conspirators one by one. In the saga, Kari ultimately does

not kill Flosi, but instead reconciles with him. This seems

at odds with the action film, where the villain always dies,

but it is important to remember the formula inherent to these

flicks. The villain is cornered by the hero, who, after hesitation,

agrees to let him live and face legal prosecution for what

he has done. In doing so, the hero elevates his violent masculinity

above that of the villain; the hero, at last and however tenuously,

has found mercy, the action-film equivalent of a deific characteristic;

by demonstrating clemency towards his arch-nemesis, the action

hero wipes out all memory of his past violence and reminds

the audience of his innate goodness, a quality easy to lose

in a sea of bad-guy blood. The villain, though, always foolishly

attempts one last great act of evil, and this is when he must

die; he leaves the hero no other option. The hero’s ethics,

then, remain unquestioned, and the audience leaves satisfied

at the just death of the villain.

In Njal’s Saga, Flosi lives, but lives wisely;

rather than attempt a futile revenge on Kari, he marries his

daughter to him, presenting Kari with a new family to replace

his old, and placing himself in the unlikely but enviable

position of having his former enemy become his protector.

This ending, though, is very reminiscent of the American action

movie; the hero “gets the girl,” as it were, and

order is restored to chaos. Kari recreates the life he had

before the burning, and in the perverted logic of action films

and Icelandic sagas, everything is back to normal.

The end result of Kari’s revenge, though, is that his

prestige is greatly enhanced. He becomes legend, the last

note of a long and winding historical saga, not simply by

surviving the tale, but by thriving in the saga’s end.

Even Kari’s enemies constantly note that “there

is no man like Kari;” even they admire his singular bravery,

tenacity, and skill. This is the true sign of the action hero;

only an archetype is admired and respected by friend, foe,

and the law alike.

Jurgen Reeder, in “The Uncastrated Man: The Irrationality

of Masculinity Portrayed in Cinema,” believes that this

enhanced prestige is the end result of the ordeal our hero

survives, and that ultimately, this ordeal “is a nostalgic

wish to find a way back to ritual forms of becoming a man.”

Reeder believes that exaggerated masculinity can only be applied

to the man who has undergone this new “ritualistic form”

for becoming a man; through this, the bar in becoming a man

is raised too high for other, lesser heroes, such as Gunnar,

Skarp-Hedrin, or Njal himself, all of whom are not only killed

(and the archetypal hero, obviously enough, must remain veritably

immortal; he must constantly face death but never succumb

to it), but contain important flaws in their characters: Gunnar

does not heed the wise advice of either Njal or his mother,

nor does he leave Iceland when sentenced to do so, and thus

dies for his sentimental foolishness; Skarp-Hedrin likewise

rashly chooses to ignore his father’s advice and also

is noted for his quick tongue and abrasive manner; Njal is

passive, a strange element in his society and very accepting

of his own fate. It seems odd to label these characteristics

as flaws; Gunnar’s sentimentality makes him likable,

and Njal’s passive wisdom makes him perhaps the most

appealing and admirable figure in the saga, at least from

a modern perspective. These flaws, however, prevent them from

becoming action heroes. The hero must fight, always, even

against terrible odds, and most especially when he wishes

not to; the hero must rid himself of worldly attachments,

save those things he fights for. The hero must be singular

and singular-minded; he must demand perfection of himself,

and he must find it, and it is this tenacious quality that

serves him best, assuring his victory.

What does it mean, then, that the Icelandic saga’s concept

of exaggerated masculinity and our own as exemplified by action

film heroes seem to be virtually identical? In a larger sense,

what type of implications does this cultural collusion have

for other popular cultural similarities that may crop up?

Are we noting that these two societies are more alike than

they seem, or that they at least shared a similar fascination

with masculinity? Or does it mean that the issue of societal

masculinity itself has plagued mankind for centuries, and

that this formula occurs in other forms of popular culture,

if one only looks for it? Do we still yearn for a ritual to

tell us we are men, like the Jewish bar mitzvah, or do we

now make the standard so impossibly high that we can never

achieve true masculinity, allowing ourselves the comfort of

not having to be like Kari Solmundarson, of not having to

suffer uncontrollably and then surrender life itself to terrible

vengeance? Perhaps this is why we live so vicariously through

these sags and movies; it is the closest any of us wish to

come to this type of exaggerated masculinity. Thus, one could

say that Kari Solmundarson in Njal’s Saga demonstrates

not what we wish to be, but that which we hope most fervently

never to become, an almost admonitory though fascinating and

compelling simulacra of potency and judicious destruction

that our contemporary culture seems just as marveled by as

the Icelandic Vikings were almost a millennia ago.

October 2003

|