I.

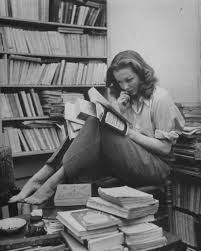

She is barefoot, perched on a stool, surrounded by books. They are everywhere: on the shelves, on the desk, on her lap. Her index finger is on her lips, and there is something approaching a smile on her face. There is an ashtray beside her feet, but she isn’t smoking. She is dressed like a vacationing Kennedy. She might be in her study, or in the library at Harvard, where in a few minutes she will head over to her writing seminar, where she will be taught by Robert Lowell, and where Anne Sexton, America’s other Patron Saint of Suicidal Depression, is one of her fellow students. Whether it was a photograph taken by a friend in a private moment, or a posed shot for one of the magazines that so often published her work, I don’t know.

What I do know: this is the version of her that I most like to think about. The Sylvia who loved literature so much that she wrote nonstop. Read her Collected Poems (where she lists the dates of when each of her poems was written) and one will find that they seemed to come as quickly and as naturally to her as hit songs did to Prince. She produced so much top-level work during her short life that it seems almost superhuman. It’s true that a lot of us love the idea of the tortured artist, and we are drawn to the often macabre stories that frequently surround the lives of our greatest talents. But I don’t. I never have. I hate thinking about F. Scott Fitzgerald throwing up in his bathroom in Encino with a perpetual hangover. I try not to picture Virginia Woolf filling her pockets with pebbles and walking into the Thames. There is enough sadness in the world without reminding myself that some of my favorite writers spent the majority of their abbreviated lives being devoured by drink, drugs, or depression.

Which means that whenever I think of Sylvia, I try to think of her like this. Clad in loose khakis and a collared linen blouse, so immersed in her books that nothing going on outside of this room could ever make her feel anything other than gratitude for the gift of being alive.

II.

The sense of affirmation the photograph possesses is in more of the poems than we often realize. In “Metaphors," for instance, where Plath describes the advanced stages of her pregnancy through a series of increasingly wild descriptions—“a riddle in nine syllables,/An elephant, a ponderous house,/A melon strolling on two tendrils"—or “You’re" (also a pregnancy poem), where her fantastical wordplay has more than a little in common with e.e. cummings: “Clownlike, happiest on your hands,/Feet to the stars, and moon-skulled,/Gilled like a fish." Though neither of these poems could ever be mistaken for Hallmark-esque celebrations of impending motherhood—they’re too charged with Plath’s impending anxiety about the respective arrivals of her babies, and how those arrivals will change her life in dramatic, even unsettling, ways—there is far too much joy here to be overlooked. Indeed, the use of similes and metaphors provide the sense of imaginative wonder one experiences in Dr. Seuss or Maurice Sendak, and her description of pregnancy is akin to a heroine in a fantasy tale, the experience possessed of the sublime and the ridiculous in equal measure.

But poems like these do not belong to the Plath canon because they would complicate the general public’s sense of her as a walking depressive, forever waiting for the black carriage that Emily Dickinson wrote about in “Because I Could Not Stop For Death." Like T.S. Eliot’s tragic Prufrock, Plath has been “fixed," “wriggling on a pin," and not enough of us are interested in returning to the work and discovering that there’s so much more in her poems than we realized. And it’s too bad. Because there are few bodies of work in American Poetry with as many different tones than hers.

III.

My favorite tone? That’s easy. It’s Plath-the-Romantic. Wordsworth’s great, great granddaughter, walking through a chilly autumn day and marveling at the unexpected gloriousness of flowers in “Poppies in October," so lovely that “the sun-clouds this morning cannot manage such skirts." They are a “gift, a love gift/Utterly unasked for/By a sky." It’s basically Plath’s version of “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud," except Plath is thousands of miles from the Lake District, and she is (understandably, given this is still the woman who wrote “Daddy"), stunned to realize how much this beauty means to her: “O my God, what am I/That these late mouths should cry open/In a forest of frost, in a dawn of cornflowers." Her use of “O" instead of “Oh" here is particularly lovely, as it treats God as a muse instead of a deity, and retroactively turns the entire poem into a psalm, something whose spiritual power will increase the more it is read, and recited.

This is where one acknowledges, with more than a touch of sadness, the role that luck plays in an individual’s life. Put Sylvia Plath in the Lake District alongside the Wordsworths and Coleridge, and publish her in the same magazines as Byron, Clare, Keats, Shelley, and Southey, and who’s to say what direction her poems might have taken? Instead, she gets stuck in the suburbs of Eisenhower’s America, where Joe McCarthy is doing his Grand Inquisitor shtick on television every evening, and the Atom Bomb lurks at the edges of the national consciousness like a militarized Grendel.

But that’s the way these things go. And anyway, Sylvia made the best of it. There’s enough pleasure in her Collected Poems to remind readers that she brought more than her share of light into the world, and it’s a light that’s still burning.

April 2017

From guest contributor Kareem Tayyar

|