Any serious discussion of Jonathan Franzen and his work requires at the very least a preliminary look at the cultural event that followed hard upon the publication of his national Book Award-winning novel The Corrections. As a few critics such as Chris Lehmann have noticed, the affairs surrounding Franzen’s overt ambivalence toward and eventual exclusion from the Oprah Book Club are decidedly germane to “the subject of The Corrections itself." Franzen hails readers into his big novel. He fragments his text in a number of ways so as to invite readers to engage with it ethically, socially, and critically. The novelist sets up these corrective, compelling engagements by way of “The Failure," an opening section devoted to his narrator’s experiences as a cultural critic at a college in Connecticut. Yet despite Franzen’s democratic representation, as an arbiter of justice Oprah has induced many readers away from the cultural critique and assessment that his narrator encourages. Undermining a democracy of reading, Oprah’s institutional correction of The Corrections and its author provides an undeniable case in point of how the celebrity’s book club – and the media age that it concurrently supports and symbolizes – contributes to unjust, not to mention anti-novelistic, reading practices.

In correspondence to the processes of just recourse, however, Jonathan Franzen appears to take action against Oprah Winfrey in his coda to The Corrections, an essay collection called How to Be Alone. The book title may even be an ironic allusion to Oprah’s curiously confidential yet divulged life story, a widely published personal “literacy narrative of progress," as R. Mark Hall phrased it, that always begins with an endorsement of reading as cure to “being alone." Complicating the simple paralegalistic terms of the Oprah Book Club, some of the essays in Franzen’s nonfiction recoup the array of ethical conditions, difficulties, and engagements essential not only to The Corrections but also to literature. In light of Oprah’s televised evaluation of him, an appraisal that perpetrates the author against his own work, Franzen reasserts his original repudiation of the promotion of a biographical and therapeutic model of reading, a model in turn sponsored by pharmaceutical and corporate interests. Franzen reclaims The Corrections as a critical judgment of capitalism in How to Be Alone. Though we cannot correct free enterprise, we must critique it, for we are not all capitalist subjects to the same extent. Despite the fact that individual American citizens are governed by similar official legal structures, not everyone has the same economic leverage as, say, Oprah.

Beginnings

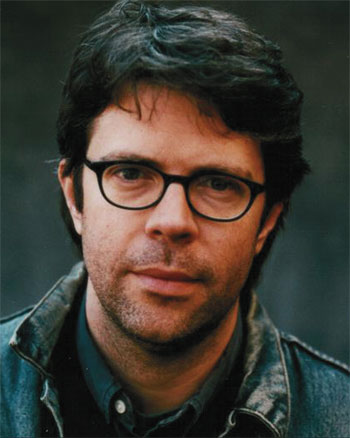

In the midst of the media’s sustained focus on fear and trembling and loathing and war after the terrible attacks in New York City and Washington, DC, in the late summer of 2001, Franzen, according to Thomas R. Edwards, “entered the history of literature and publicity simultaneously." Within the same month, he at once took home the National Book Award and an invitation to the Oprah Book Club. The extensive enthusiasm surrounding the author just over forty was short lived. In a move without precedent, the woman who fights injustice officially withdrew her invitation: “Jonathan Franzen will not be on the Oprah Winfrey Show because he is seemingly uncomfortable and conflicted about being chosen as a book club selection." Franzen’s attempts to explain his dis-invitation from the self-made billionaire’s popular show (even though book club segments are her least popular) only made matters worse. Visibly flustered by his newfangled role as overnight icon, and exhausted by the countless interviews attending his book tour, he made the mistake, as he himself puts it, of “conflat[ing] ‘high modern’ and ‘art fiction’ and use[d] the term ‘high art’" in order to explain his literary influences. Describing this incident, critic Joseph Epstein points out that an “artist can say almost anything he wants as long as he manages not to commit the cultural sin of elitism." In the image age, notwithstanding Adorno’s dogged doings, an elitist is a paper tiger indeed.

Unsurprisingly, the popular media aimed their reviews and stories at the author himself. Franzen the man became the dominant narrative, in lieu of his actual work. His fame as a fiction maker was soon replaced by what Christoph Ribbat has termed his infamous “cultural arrogance." Generally disparaged for his distrust of corporate emblems – i.e., the Book Club logo – and his undiplomatic, honest, all-too-honest estimation of Oprah-endorsed selections – i.e., some good books, enough one-dimensional, schmaltzy ones – Franzen was hailed, Charles Paul Freund reminds us, as “The Snob Who Dissed Oprah." No friend to the author, Freund goes on to patronize America’s latest villain for his unrehearsed statements: “Poor Franzen, that’s as close to the role of Judas as the culture offers." Fittingly, what gives birth to this biblical mark is a return to “St. Jude." In other words, Franzen’s fast fall from repute to ill repute has its source at the real source of the fictional St. Jude, where The Corrections begins and ends.

In the essay “Meet Me in St. Louis," Franzen recounts his experience with Oprah’s B-roll footage personnel in St. Louis after his nomination into the book club. In spite of his avowal that St. Louis has nothing to do with his present life, he was informed by one of Oprah’s producers that these preplanned B-roll filler-shots (as what he dubs a “dumb but necessary object," a “passive supplier of image") were to be spliced with A-roll footage of him speaking. As the essay begins, Franzen finds himself looking west over the Mississippi River from rundown East St. Louis where he and Oprah team are seemingly “plotting by the side of a road" but actually “doing nothing more dubious morally than making television." Their goal, Franzen clarifies, is to capture the former St. Louisian driving to his boyhood home of decades ago in Webster Groves via the Poplar Street Bridge, with stops at the Old Courthouse and the Arch along the way. Franzen’s role is to appear “what? writerly? curious? nostalgic?", while he dutifully “pretend[s]" to “reexamine his roots." Adhering to a script and coached by B-roll producer Gregg, Franzen only half succeeds at looking “contemplative" in a number of locations in his old suburban neighborhood, including under the oak tree commemorating his father. Unable to emote justly beneath his father’s tree, he at last informs the crew that this sentimental TV moment is “fundamentally bogus." Yet, unable to go on, the difficult author goes on. For the next hour, he is captured contemplating trains at the Museum of Transportation, his first visit to the place. Franzen’s unresolved impromptu remarks about the Oprah Book Club followed not long after this stylized day.

In his book Late Postmodernism, Jeremy Green offers an extensive scrutiny of Franzen’s run-in with Oprah. He starts off his analysis of this media exhibition by pointing out that there is “something almost Franzenesque in the comic desperation of this drama." “[A] brilliant success," Green continues, “gives way to disaster because of a few ill-chosen words, and the mess grows more intractable with every attempt the protagonist makes to extricate himself." Green is not alone in this detection. Chris Lehmann and Christoph Ribbat likewise provide variants on the connections between the fictional makeup of The Corrections and its non-fictional fate in the media market. Lehmann sees Franzen as the victim of a “pathetic spectacle" by “a newly apprehensive, war-torn nation [that] was repairing to the bracing, morale-boosting tonic of cultural warfare." Going on to speak more generally about literature, Lehmann laments that the “somewhat complicated response to his Oprahfication that Franzen tried to voice was not a permissible attitude; never mind that this very sort of ambivalent self-questioning is among the signal qualities that define good literature (popular, ‘high art,’ and anything in between)." Ribbat, for his part, likens what he calls Franzen’s “programmatic statements," that is, his “self-positioning in the American literary tradition" through “essays, interviews, and public statements," as a non-fictional illustration of the character-centered, un-ironic, modernist realism that drives what has variously been called new conventional or late postmodern or post-postmodern fiction. Ribbat makes clear that the author of the “post-postmodern" novel The Corrections plainly “places the ‘protagonist first’ – i.e., Jonathan Franzen." The aftereffects of the Franzen-Oprah breakup are at once comedic, misfortunate, and telling.

Performances

Whether he calls it a desperate drama, a pathetic spectacle, or an example of self-placement, each of these three defenders of Franzen focuses on the staginess at the heart of the Franzen-Oprah entanglement. The set-up nature of his appointment to the club, so Franzen later implies, was apparent from the beginning. If the essay title “Meet Me in St. Louis" is not indication enough, the author’s twice-expressed desire to be filmed in New York instead of St. Louis (where he had not lived for twenty-four years) should be. That the unremarkable Midwest milieu of St. Jude featured in The Corrections comes to be equated with a particular area in suburb-beset St. Louis intimates what can be characterized as the autobiographical-confessional, redemptive-therapeutic aim of the Oprah Book Club. After all, in terms of Franzen’s fiction, the sole evidence suggesting that St. Jude may be situated in St. Louis is tenuous at best. The Meisners, who live next door to the Lamberts in The Corrections, initially show up as minor characters in his first novel, The Twenty-Seventh City. They are Franzen’s lone intertextual figures. Complicating matters, though, is the fact that Chuck and Bea Meisner are exceptional only insofar as the location of their home in The Twenty-Seventh City is conspicuously left unrevealed, a fact that works against the tendency in this novel for characters to be presented in respect to where they live exactly. In terms of their lack of explicit setting, the Meisner couple stands alone – with the exception of the Lamberts, of course. That is, until Oprah’s patently naïve reading, anyway.

Ominously staging the “we" of the club against the “you" of the author, the Oprah people, when they first contacted him, told Franzen that his novel was “a difficult book for us." Still, right after this admission, and probably even before it, and perhaps even before reading the book, the Oprah team as usual removed the “difficulty" from the novel. Given the sorting classification that heads the first edition of The Corrections, this may have been a simple open and shut case. According to the Library of Congress logging data, The Corrections is about married women, Parkinson’s disease, parents and children, and the Middle West. Such a “cataloguing note," Thomas R. Edwards remarks, “sounds just right for Oprah’s club." Appropriately, the directions in which Franzen was stage-managed, both to St. Louis and in St. Louis, all as part of what he was advised were the “responsibilities of being an Oprah author," also play right into “the talk show’s therapeutic vocation," as Jeremy Green describes it. The author and his work, to put it plainly, are systematically co-opted into the ideological contrivance of the Oprah show.

Marketing campaigns led by Oprah’s book club correct the satirical author and harness him to the will of capitalism. No matter what he says, no matter how he resists “branding" in the marketing sense of the term, he is recast in particular media roles after Oprah corrects his market value as a novelist. Irrespective of Franzen’s fictional and personal efforts, capitalism cannot be corrected, much less criticized, it appears. Once drafted into the club, a club that unjustly brands or positions the novel, the author, and the audience as aligned subjects of a curative market culture, Franzen was roundly reprimanded (even by usually savvy critics) for exerting artistic individuality and difficulty as his own justice – in addition to his own justification. A badge of honor, the self-autonomy he willfully exerts counteracts the group-reliance Oprah’s show venerates.

Green spells out the plain link between book club picks and talk show topics. He explains how the “sentimental and melodramatic works of fiction" that Oprah typically chooses are “novels that turn around the kinds of problems dealt with on a regular basis on her show – spousal abuse, racism, overeating, bereavement. The narrative focus of these texts informed the content of the discussions featured on the show, wherein the sufferings of characters were likened to the sufferings of Book Club participants." The ethos of the show, of course, focuses on the connection between confession and identification. Adamant about the biographical nature of fiction, Oprah sets up sappy pans and zooms of authors ostensibly emoting under oak trees. These shots aim to encourage the situating of book clubbers within selected books in the same way that they position respective authors within their own books. As Green recounts, Oprah pushes her viewing and reading public either into “confirming the shape of experience (‘my life is just like that’) or [into accepting] a model to emulate (‘my life should be more like that’)." With her “para-social" strategy of “imagined or constructed intimacy," as R. Mark Hall phrases it, Oprah in effect pathologizes identification, therefore ensuring the continued popularity, not to say success, of her series. On the talk show scene, personal problems are played out on a public stage. Actors spell out their tribulations knowing that the audience is prepped to commiserate as they spectacularly consume. The problem then enters the public domain, no longer shouldered by one single Sisyphus. Always jostling, actors and audiences forever return, knowing they will identify to no end and hoping they will be emulated against all odds – just like Oprah.

While he was being filmed over and over under his father’s tree, a tree bordered by his mother’s ashes (he was wise to “make [him]self forget," Franzen may also have envisioned himself and his latest novel being bandied into an even greater would-be plan of Oprah’s. Tactically promoted as a novel about illness and homecoming, about healing and redemption, The Corrections could very well be packaged into a predictable agenda of post-9/11 therapy. Incongruously espousing providence, Oprah could simply brand and dismiss The Corrections as “the great American novel arriving just in time to heal our troubled nation," or something like that. After all, Oprah, whom Bonnie Greer describes as the woman who “control[s] the publishing world," first commends The Corrections as “funny, familiar, insightful, and disturbingly real." And, unilaterally curtailing debate over the literary merits of Franzen’s novel (at least among the more naïve of her viewers), the decisive Oprah proclaims, “When critics refer to ‘The Great American Novel,’ this is it, people." This style of one-dimensional and purpose-directed reading epitomizes the Oprah approach to fiction, which Hall calls an anti-novelistic method that “promote[s] [Oprah] herself" while at the same time overlooking or disallowing “other ways of reading."

An extract from a transcript of Toni Morrison’s fourth appearance on the show illustrates how Oprah reduces refinement and range into a take-home recipe. Also disquieting, a contemporary iconoclast could theorize that the television transmission featuring Paradise concludes with the jaded joviality of a cynical autocrat. Effectively disregarding the last remarks of her notable visitor, who was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1987 and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1993, among a host of other literary distinctions, Oprah endorses her own personal celebrity as the standard of literary authority. She does not only inform her viewers about what to read. As a TV icon, Oprah also tells them, as well as her guest in this instance, how to read:

Ms. Morrison: You have to be open to this – yeah, it’s not just black or white, living, dead, up, down, in, out. It’s being open to all these paths and connections and [unintelligible] between.

Winfrey: And that is paradise!

Ms. Morrison: That is paradise.

Winfrey: And that is paradise. Marvelous. That’s great. Paradise is being open to all the places in between.

Taking the full installment of this book club show into account, Green summarizes what he sees as “the problem [Oprah’s] medium has in dealing with such intricate [literary] matters": “Morrison’s speculative comments are translated into a slogan, rather as if the discussion must close with a pithy formula that the viewer might take away from the show, without regard for the preceding difficulties and elaborations." Green finishes with the declaration that the Oprah project eschews “cultural dialogue" in favor of a purported optimism that solicits the personalization of the “textual encounter." In spite of Franzen’s obvious effort to correct his would-be host, and Morrison’s delicate attempts to correct her actual host, Oprah’s gullible therapeutic reading model confuses the distinction between the curative and paying lip service to the curative. Whether chastising Franzen or abridging Morrison, Oprah shuts down any semblance of productive critique or discourse. Without aspiring to “correct" capitalism or racism or chauvinism or egotism, the “teacherly" and “preacherly" book club, Hall explains, makes life simpler and easier, an improvement arguably acquired by way of merely buying into Oprah’s commercial telecasts, both emotionally and monetarily.

Readings

Considering Franzen’s most popular work before the publication of The Corrections, a long 1996 Harper’s essay first titled “Perchance to Dream," later edited and mordantly renamed “Why Bother?," the author’s candor with Oprah’s B-roll producer after he was obliged to gesture like a faux-Beckettian mime under a tree almost seems like the stuff of an overwrought narrative. Before the orchestrations of the Oprah team, the figure makes public his strong motion against what he sees as “the therapeutic optimism raging in English literature departments," an indictment that probably includes the debate-free salve of a televised book club. In the same essay, he discloses his personal anxiety over what he as a novelist sees as the “hyperkinesis of modern life." According to him, this almost time-lapsed Zeitgeist integrates “mass suburbanization," “at-home entertainment," “virtual communities," and “Zoloft," all of which compromise the place of traditional “linear reading." A champion of the low-tech, the figure also looks back to the technological prints that signal his overt malaise with modernity: “Just as the camera drove a stake through the heart of serious portraiture, television has killed the novel of social reportage." So when this same figure gets a chance truly to engage with popular culture (and, all the better, with the “average" wife or husband, the bachelorette or bachelor “whose life is increasingly structured to avoid the kinds of conflicts on which fiction, preoccupied with manners, has always thrived"), he accepts in good faith.

Jonathan Franzen, however, soon found himself being drafted into the very “technological consumerism" he satirized. After a day of being bullied around a setting that was no longer his, he came to dread the end product of the theatricalized images the TV camera attributed to him personally. Sensing that his engineered image was undergoing a process of “extraction, reduction, and recombination," as Michael Sorkin might describe these media machinations, Franzen realized that he was unexpectedly sponsoring the cultural conditions that he aimed to challenge. As an Oprah author or un-ironic citizen-subject, he was recruited to relay a “tight connection between self-realization and pure consumerism," to appropriate David Harvey’s phrase. Yet when Franzen made these discomfiting concerns public, for the second time as it were, he was met with scorn by the media, by past Oprah authors, and even by some literary critics. Such was the case after he voiced his uneasiness with the Oprah emblem, never mind that a central trope in The Corrections details the pervasiveness and privileged positioning of the Mid-Pac logo, an abbreviation for the restructured Midland Pacific Railway, a subsidiary of W–Corp, owned by the invisible Wroth brothers, who appear to have actual and imagined vested-interests in everything from pharmaceutical production and distribution, to high tech industries, to university endowments, to prison building, to hallucinogenic drug culture, to the video gaming of children’s literature. This novel-length critique of the unchecked sway of a corporation, a control that can trickle down and out to every strata of culture through a popular logo alone, ought to be word enough to readers that the author might himself distrust, and want to expose, not to mention displace, the motives behind a corporation’s sponsorship – especially for those readers and critics who prove incapable of distinguishing the divide between a narrator and his creator.

In “Surfing the Novel," essayist Joseph Epstein levies what can be seen as one of the more customary attacks upon Franzen following the author’s “run-in with Oprah Winfrey," a woman Epstein describes as “the nation’s most powerful literary critic." Though he acknowledges that Franzen is a “talented writer," Epstein takes him to task for two principal reasons. First, he looks back at the Harper’s article and dismisses it as a “great clown’s baggy pants of an essay, [where] Franzen pulls out every rubber chicken, toy trumpet, and whoopee cushion of literary snobbery of the past forty years." Afterward, Epstein moves through a few of the elements in The Corrections that he finds unappealing – the “grotesque family," the “flimsy clothesline" of a plot, and “the depth of [Franzen’s] disdain" for his characters – before he settles on what he labels the vital “element that is entirely missing from The Corrections: a moral center." Although Epstein begins by charging Franzen with literary snobbery, a cursory look through some of the critic’s own essays, found in Life Sentences, Partial Payments, and Plausible Prejudices, for instance, reveals that he too appears to be a literary elitist. Not even one of the authors who shared the bestseller list with Franzen appears in Epstein’s discursive work. No Robert Ludlum nor Danielle Steele; no Mary Higgins Clark nor John Grisham. Moreover, a perusal of Epstein’s recent book Snobbery (2002) indicates the same trend. While Epstein accommodates noteworthy figures from Henry Adams to Philip Ziegler, includes celebrities between Rodney Dangerfield and Andy Warhol, and also mentions Walter Cronkite, Dan Rather, and other media personalities, not once does he refer to a writer of typical bestseller status. To be sure, popular authors manifest a modicum of social discernment as well, whether in their work or in person.

After close inspection, furthermore, Epstein’s reading of Franzen closely resembles the undemocratic and perfunctory readings of many post-Oprah Franzen critics. Like reviews by Nicholas Blincoe, Bonnie Greer, and James Wolcott, not to mention the first half of an appraisal by Valerie Sayers, the ex-girlfriend to whom Strong Motion remains dedicated, Epstein’s estimation of The Corrections reads more like a judgment of its author. Like everyone, he wants to correct Franzen. A markedly candid arbitrator, Epstein admits to having “ceased reading The Corrections" halfway through, “before [he] knew [he] was going to write about it." This sincere gesture, however, incriminates the judge himself. With his apparently impromptu confession, Epstein sheds more light on his own reading practices than he does on Franzen’s actual novel. Paired with the complaint that The Corrections lacks a moral center, Epstein’s approach to literature begins to convert into a weird variant of the Oprah approach. Outwardly unable to locate a succinct statement that might sum up the message of the text, he quits it. Subsequently, he rereads the novel in its entirety in order to dismiss it in a few words.

Additionally, aside from his proclamations against the Harper’s essay, which clearly suggest that he has read it, Epstein overlooks how Franzen counteracts Oprah-style therapeutic optimism with what he describes as “tragic realism." Near the end of his well-known essay, Franzen writes, “I hope it’s clear that by ‘tragic’ I mean just about any fiction that raises more questions than it answers: anything in which conflict doesn’t resolve into cant. (Indeed, the most reliable indicator of a tragic perspective in a work of fiction is comedy)." Perhaps exposing Oprah’s approach to fiction as dictatorial, the serially corrected novelist and essayist continues, “The point of calling serious fiction tragic is to highlight its distance from the rhetoric of optimism that so pervades our culture. The necessary lie of every successful regime, including the upbeat techno-corporatism under which we now live, is that the regime has made the world a better place."

When Epstein attacks The Corrections for what it lacks, he really seems to be demonstrating what his reading of The Corrections lacks. The Corrections has no moral center because its author decries resolving novelistic conflict by means of a humbug dictum. Franzen, to put it differently, refuses to incorporate markers by which a character’s correctness can be calculated. What The Corrections does not lack, but Epstein’s vision of this particular novel does, is an embedded awareness that the tragic can be viewed through a comedic lens, a view that makes ambivalence and difficulty and conflict all the more sophisticated and stirring. Epstein’s overstated disdain for what he highlights as Franzen’s disdain for his characters, blinds the critic from one of the more refined representational constructs of this novel: its mode of narration. Even though The Corrections is Jonathan Franzen’s novel, it is not his individual story. The complicated fictional sequence of events belongs to Chip Lambert, who is Franzen’s clandestine narrator.

June 2008

From guest contributor Jason S. Polley, Assistant Professor at Hong Kong Baptist University |