Through the Looking Glass of Silver Springs:

Tourism and the Politics of Vision

Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture

(1900-present), Spring 2004, Volume 3, Issue 1

https://americanpopularculture.com/journal/articles/spring_2004/king.htm

Wendy Adams

King

University of South Florida

Introduction

An Enya musical score drifts down from the white rafters of the

Victorian boat dock then floats around the meticulously manicured

curves and intense colors of the surrounding tropical landscaping

(see Figure 1). In the company of strangers, my family and I wait

in a small line to board the Chief Yahalocee, one out of a small

fleet of Silver Springs's famous glass-bottom boats. I cannot

help feeling a bit skeptical. How can an old-fashioned tourist

gimmick, such as the glass-bottom boat, compete with the cyberspace

spectacles and multi-media extravaganzas so readily available

today? My barely nine-year-old daughter is already a seasoned

veteran of Space Shuttle launches, the Museum of Science, IMAX

surround-sound movies, Disney and Busch Gardens virtual reality

rides, all supplemented with a daily diet of DVDs and video games.

What fascination can plying across the river, peering down at

aquatic life through a transparent pane of glass encased in the

bottom of a small boat hold for sensation saturated and technologically

savvy tourists of the twenty-first century?

Figure 1

At the turn of the twentieth century, however,

much of the appeal of Silver Springs (Florida's oldest tourist,

theme park) and the glass-bottom boat tour was not unlike the

interest that Space Shuttle launches and IMAX movies possess for

many tourists today. During the nascent days of Florida's

budding tourism industry, in the late 1870s, Phillip Morell invented

the glass-bottom.1 (Later, Hullam Jones's 1878 version

was made from a three-foot hollowed out cypress log.2) The relative transparency

of the Silver River's waters coupled with the glass bottom

of the boat promised Silver Springs tourists beauty, motion, and

spectacle while also offering them a scientific education, a sense

of national pride, and a sense of cultural progress (see Figure

2). As cultural historian Susan Davis contends, "Every culture

uses nature metaphorically and the natural world provides not

only all means of material life but a common, human currency for

representing ideas about that life as society and culture"

(30).

Figure 2

Illustrating Davis’s point, the privileging

of vision (an outgrowth of the scientific revolution),3

a privileging which informs the design and promotion of the glass-bottom

boat, intertwines with American social constructions of nature

over the last 125 years. Upon the Silver River's waters

and within the glass-bottom boat, the social significance of America

and its landscape is negotiated within tensions among romantic,

scientific, and cinematic visions. An amalgam of Western myth

and Renaissance, Enlightenment, and Romantic ideals is used to

frame Silver Springs as an edifying landscape of personal, spiritual

and scientific national importance. Like the

destinations of the American Grand Tour, rhetoric surrounding

Silver Springs is indicative of the larger role tourism and spectacle

play in the quest for a national cultural identity bubbling forth

out of an America in the wake of modern industrialization.4 As cultural critics such as John Sears, David E. Nye, and Mark

Neumann suggest, in many ways the act of tourism and the national

park itself, in the United States of the nineteenth and twentieth

century, functioned as a public space that attempted to help define

and unify American culture and its heterogeneous population.5

A Romantic

Vision:

The Quest for the Sublime and Picturesque

As the craggy, yet cheerful, voice of our gray-haired captain

welcomes all aboard, each of us dutifully awaits our turn to climb

up and then down into the belly of the boat. Sinking into the

water, now fully loaded with shorts-wearing tourists, armed with

shiny cameras of all varieties as well as with the occasional

juice-stained sippy cup, the boat slowly slides backward from

the dock (see Figures 3). "Bubbles!" squeals a

toddler. To everyone's delight, thousands of tiny bubbles,

like those in a freshly poured ginger ale, start zipping across

the glass. In these shallow waters, the captain briefly lectures

over a small buzzing speaker, trying to compete with the scratchy

grind of tall river grasses rubbing against the boat's transparent

bottom. As we reach a clearing, the captain instructs all passengers

to look down at the dizzying depths of the first Silver Springs

cavern on our tour. "What is under water you will be able

to see clearly," he repeats. At this point in the

tour, he proclaims that the glass-bottom makes visible the overwhelming

beauty and scientific knowledge encased within the Silver River's

crystalline waters. As he promotes the park, I muse to myself

that it has changed very little in the 125 years since Silver

Springs first captured the imaginations of nineteenth century

travelers (see Figure 4).

Figure 3

Figure

4

By the mid-nineteenth century, Romantic and Transcendentalist

views of nature as a sublime and picturesque landscape had become

an essential part of experiencing nature for many leisure and

middle-class Americans. Patricia Jansen argues in reference to

tourism in Niagara Falls, for example, "The importance of

the sublime as an element in both elite and popular culture was

well established by the late eighteenth century...The craze

for sublime experience entailed a new appreciation of natural

phenomena" (8). John F. Kasson as well contends that aesthetics

of the sublime and picturesque commonly superimposed on to the

American landscape at the turn of the century exemplify the hegemonic

genteel values promoted by elite "official" culture.

Leisure class values such as the quest for the sublime, according

to Kasson, filtered down to the masses (who would later visit

Florida and Silver Springs) via mass-produced periodicals and

the agents of culture such as museum curators and educators. "Genteel

reformers founded museums, art galleries, libraries, symphonies,

and other institutions which set the terms of formal cultural

life and established the cultural tone that dominated public discussion,"

writes Kasson, "as nineteenth-century cultural entrepreneurs

sought to develop a vast new market, they popularized genteel

values and conceptions of art" (4-5).

The genteel values and aesthetic conventions

constructing a Romantic sense of the sublime and picturesque greatly

contribute to American notions of national identity and leisure.6 During the nineteenth and

early twentieth century, these values and conventions were central

to the history of Silver Springs as an image of America as paradise.

The American leisure class traveler's quest for the sublime

and beautiful in Florida is revealed in images of Silver Springs

even before the glass-bottom boat was invented. In

1860, Hubbard Hart expanded his successful stagecoach line that

ran between Palatka, Silver Springs, Ocala, and Tampa to include

a steamboat that toured the Ocklawaha and Silver rivers. Hart's

steamer passengers embarked on a two-day journey that followed

the coffee-colored waters7 of the alligator lined Ocklawaha River (Upper St. John's)

up into the crystal clear water of Silver Springs.

The first written accounts of the Silver Springs

steamboat tours illustrate the significance of genteel aesthetics,

Romantic conventions, and American nationalism in the early reception

and twentieth century development of Silver Springs as a tourist

attraction and registered Natural Landmark.8 And as Nye argues, "The American sublime transformed the

individual's experience of immensity and awe into a belief

in national greatness" (43). The nineteenth-century travelers,

who had the time and could afford to travel to Florida in significant

numbers, often used the Western literary and fine art canon to

frame their experience and the Silver Springs steamboat tour as

a sublime spiritual journey. Florida history and architecture

historian Margot Ammidown, for example, contends that "many

of the written descriptions of the early trips to the springs

seemed to equate the journey with a spiritual transition to the

afterlife, or to refer to the time-honored notion of the river

as a metaphor for a spiritual journey to the source, which, with

the advent of tourism, became a regular mini-pageant acted out

on the Ocklawaha" (245). For instance, Ammidown cites the

letters of nineteenth-century anthropologist Daniel Brinton (who

is also quoted in the contemporary Silver Springs book) who described

his journey as "one of the most dramatic transitions from

darkness into light that a traveler can make anywhere on the continent"

(qtd. in Ammidown 245).

Such nineteenth-century visitors as Daniel Brinton, Constance

Fenimore Cooper Woolson and George McCall described Silver Springs

using Western myth, Romantic ideals, and European and American

landscape oil painting conventions. Brinton, Woolson and McCall's

imagery evokes the iconography of the sublime described by American

Transcendentalists like Emerson, painted by Hudson River School

artists, and later examined in the twentieth century by philosophers

such as Heidegger. In the 1856 history Notes on the Floridian

Peninsula, Brinton exclaimed, "Slowly drifting in a

canoe over the precipice I could not restrain an involuntary start

of terror, so difficult was it, from the transparency of the supporting

medium for the mind to appreciate its existence" (186).

Woolson commented in 1876 that "the water was so clear that

one could hardly tell where it ended and the air began...the

fish swimming about were as distinct as though we had them in

our hands; in short...it was enchantment" (30). And

George McCall, while serving in Florida during the Second Seminole

War, wrote, "We were stationary...in a moment all

was still as death. The line of demarcation between the waters

and the atmosphere was invisible. Heavens! What an impression

filled my mind at that moment! Were not the canoe and its contents

obviously suspended in mid-air like Mahomet’s coffin?"

(150).

The intensely disorienting and enlightening collapse of space

and time, described by Brinton, Woolson, and McCall, is an essential

component of the Romantic and Transcendentalist vision of the

sublime, vast, natural landscape. The blurred boundary as the

celestial and terrestrial dissolve in the transparency of Silver

Springs's waters resonates with Emerson's Transcendentalist

vision of the transparent eyeball. Like Emerson's communion

with the natural world recounted in Nature, the water

and surrounding landscape of Silver Springs act as a catalyst

to the sublime experience believed to initiate a similar reintegration

with the divine. Woolson and McCall become "a transparent

eye-ball," "nothing," "all," "part

or particle of God" (17). The disconcerting elements (a

degree of danger and powerless to the experience itself) implied

in Brinton, Woolson, and McCall's choice to compare experiences

on the Silver River to "terror," "enchantment,"

"death," and suspension "in mid-air" illustrates

what Heidegger regarded as the "sublime moment, in which

anxiety is preparation of insight into the whole" (Wilson

155). The anxiety and sense of the ineffable present in Brinton,

Woolson, and McCall's portrayal of Silver Springs also recalls

Kant's 1870 (about the same time the glass bottom boat appears)

distinctions between the aesthetics of the sublime and picturesque.

The Kantian sensation of the sublime is characterized by a mix

of pleasure and pain experienced in a moment when the mind is

overwhelmed, pained at its inability to grasp fully ideas intuiting,

not imagining, the infinite, the total (Wilson 20). The disorienting

amorphous space described by Brinton, Woolson, and McCall also

exemplifies the asymmetry, the formlessness versus the harmony

of form of the picturesque as defined by Kant.

Today, the sublime and picturesque qualities of Silver Springs

are interrupted by the activity of tourists and toddlers as well as the

motion of the boat. Now, we float above the Spring of Fire, and

our Silver Springs glass-bottom boat turns dramatically leftward

as the captain explains that the spring's name comes from

the tiny volcano-like forms spewing out of the cavern. Like liquid

in a slow turning glass, I feel as if I am moving in the opposite

direction of the boat, only to meet back with myself at circle's

completion. "Whoa," whisper several fellow riders.

Disoriented and a little woozy, the majority of the tourists nonetheless

remain hunched-over, looking through the rectangular frames of

glass in the boat's bottom at the luminescent fish and rock

formations below. The boat glides to its next stop entitled the

Blue Grotto. Frances Kenneley's Discover Silver

Springs: Souvenir Book reports that the grotto's moniker came from the cerulean hue reflected from sunlight

filtering through the water" (14). I am not entirely

convinced. In addition to the spring's blue waters, the

well-known, exotic Blue Grotto of Italy or even the infamous Love

Grotto of Tristam and Isolde, made popular by Romantic writers,

must have influenced its naming.

The captain announces the next stop as The

Bridal Chamber. Written over sixty years before my Discover

Silver Springs: Souvenir Book (first copyrighted in 1994),

a 1930s Silver Springs brochure exemplifies how the promotion

of Florida and Silver Springs as a rejuvenating, romantic paradise

(in the genteel Romantic tradition) changed very little even as

the demographic of Florida tourism drastically shifted.9 As the nineteenth century gave way to

the twentieth, so did the steamer to rail and car. By the mid-1920s,

the Florida vacation was no longer restricted to the elite. The

leisure class Victorian travelers, with which early Florida robber

barons like Flagler sought to fill their luxury hotels, eventually

were outnumbered by a new wave of middle class tourists owning

automobiles. The affordable mass-produced cars and subsequent

American highway systems, financed by the Coolidge Prosperity,

made the state available to middle class tourists and homesteaders

(Allen 227). Tin Can Tourists packed up in the new family car

and left for vacation. They flocked southward to visit the state's

attractions and even scrambled to purchase small pieces of Florida

paradise. Record numbers of tourists even landed permanently in

South Florida to live in communities, steeped in Mediterranean

fantasy architecture: towns such as Coral Gables, Hollywood-by-the-Sea,

and Venice-of-the-South. Evidence to Florida's popular appeal,

Miami alone experienced an influx of 2.5 million people in 1925

(Gannon 77).

Although more middle-brow educational exhibits and working-class

snake milking and alligator wrestling side shows were added to

Silver Springs when Ross Allen opened his Reptile Institute in

1931, the genteel promotion of the park as a sublime and picturesque

paradise changed very little. Writers of the 1930s brochure

compared the park to the idyllic Elysian Fields, and like the

much earlier descriptions of Florida by fifteenth-century French

explorer Ribaut, much of the pamphlet is devoted to framing Florida

and Silver Springs as a picturesque earthly Paradise. Descriptions

of the multitudinous plants and animals in Florida focus the reader

on the fecundity of the earthly garden. The brochure boasts of

rare aquatic life visible through Silver Springs's crystal

clear waters. In fact, the brochure told readers they would see

"more than 43 varieties of fish, turtles and fresh water

shellfish." Also attesting to the Eden-like fertility imagery

used to promote the park, the pamphlet notes that plants even

"bloom and bear fruit under water." Not only are the

plants and animals abundant in Florida's bountiful landscape,

they are "bewitchingly beautiful, rare and exotic."

While the long lists of plants and animals at Silver Springs evoke

the natural abundance most often associated with earthly paradise,

the descriptions of the individual's experience within the

park's surrounding natural beauty best illustrate the construction

of the park as earthly paradise in the Romantic image. Stressing

feeling and the exotic, the text places the reader in an utopian

fantasy landscape by making promises to "all who enter."

Silver Springs, according to the Grest Depression era brochure text

from Richter Library, intrigues and fascinates:

Here is a scene that intrigues the imagination – more fascinating

than anything you have seen, more beautiful than dreams can imagine,

for Silver Springs is in truth the Elysian Fields of America.

They who enter here leave all cares behind them. Individual worries

become petite and insignificant when one is communing with Nature

at her loveliest.

This text reflects the Romantic and Transcendentalist desire to

escape from civilization into the rejuvenating arms of sublime

nature. Simultaneously evoking the dwarfing landscapes often associated

with the sublime and restorative powers of nature, the text boasts,

"Worries become petite and insignificant when one is communing

with Nature." Also, the description of the caves and springs

suggests the overwhelming and sometimes limitless rocky landscapes,

rushing waterfalls, and flowing rivers frequently seen in Romantic

landscape paintings and poetry. The text further emphasizes emerging,

flowing water and a large cavern: "Silver Springs is really

a subterranean river springing from the earth through a vast cavern

65 feet long and 12 feet high." Including the aesthetic

quality also integral to the Romantic view of nature, tourists

do not only get the opportunity to commune with Nature at Silver

Springs; they commune with "Nature at her loveliest."

The direct comparison to Elysian Fields also works in conjunction

with the images of the sublime and beautiful nature connoted in

the text. The mythical reference not only evokes the image of

paradise so often associated with Florida, it also suggests the

exoticism, myth, and idyllic past used so often by Romantic poets

and painters. As Wordsworth wrote in "The Prospectus to

the Recluse" –

Paradise, and groves

Elysian, Fortunate Fields – like those of old

Sought in the Atlantic man – Why should they be

A history only of departed things,

Or a mere fiction of what never was? (399)

Silver Springs as Elysian Fields metaphor goes from Romantic nostalgic

reference to idyllic mythological landscape to edifying sublime

nature, elevating the springs to authentic space contrasted against

the artificial man-made trappings of civilized society. The metaphor

illustrates the efforts to exult American landscapes in order

to characterize American culture as equal to, if not superior

to, European culture. The beauty of North America presented as

"evidence" to a unique presence of the divine in the

United States also supported the popular notion of Manifest Destiny.

Charles Sanford noted that American artists Thomas Cole and William

Cullen Bryant, for example, "had need of the sublime to

celebrate what they felt was peculiar and unique about American

scenery" (qtd. in Nye 24). Neumann, Nye, and Sears contend

that American romantic landscape tourism ironically functioned

as a source of cultural production. Within the context of the

America First tourism campaign, Silver Springs as the true Elysian

Fields connotes that the American landscape even exceeds in importance

and authenticity the one imagined by the culture of the Golden

Age of Greece so revered by American gentility and the European

elite. As Neumann argues, the effort to frame places such as Silver

Springs as the true site of ancient myth and literary reference

"fits well with the federal mandate to promote American

scenery as superior to that of Europe; it's part of a quest

for antiquities." The presence of Romanticism and the quest

for American antiquities remain at Silver Springs today in the

"Indian legends" and ancient fossils featured so prominently

at the park.

The Chief Yahalocee moves forward. Several adults join the small

children who much earlier abandoned the official position of scientists

leaning over microscopes, examining the invisible world revealed

by its lens, in favor of letting the wind blow on their faces

as they stare at the open-air view of trees, terrestrial animals,

and the surface of the water available through the open deck windows.

At our captain's request, many passengers again look down

through the glass bottom of the boat at the rock formation and

jetting spring below. Stopping to float above the Bridal Chamber

spring, the captain tells its legend. The Bridal Chamber is named

after the tale of the ill-fated love affair of Indian Prince Chulcotah

and Winona. She hurled herself into the deepest point of the river

in a moment of agonizing grief over her forbidden love for the

Prince.

It is interesting to note, however, that the

Legend of the Bridal Chamber told today is different from that

quoted in the Silver Springs brochures spanning from the first

half of the twentieth century.10 Still a romantic tale of "star-crossed lovers," earlier

promotion cites the tale of Aunt Silla, "a 110-year-old

negress," who recalls when her "honey child,"

Bernice Mayo, a poor, yet beautiful maiden, who wasted away after

her wealthy lover's father refused to let them marry. On

her deathbed, the withering Bernice, asked Aunt Silla to drop

her into the big Boiling Spring (now the Bridal Chamber). Like

Ophelia, Bernice's frail, porcelain white body gracefully

spiraled downward as the crevice in the riverbed opened welcoming

her. Her lost love, Claire, happened to be rowing by the spring

with his new fiancé (a cousin-bride chosen by his father).

The sparkling light from Bernice's bracelet, a token of

his love, captured his attention. Knowing it was his old love

reaching upward from the rock, Claire dove downward into the opening

that shut and enclosed him within the riverbed with Bernice for

eternity.

The changing Bridal Chamber legend is yet another example of the

ways in which issues of race, class, and gender are often played

out within Florida's tourist spaces. Interestingly, the

"negress" tale metamorphoses into an "Indian"

version of Romeo and Juliet as more progressive attitudes toward

African-Americans evolve. Unfortunately, the Aunt Silla caricature,

an example of the age-defying "primitive" seer stereotype

(African-American film director Spike Lee recently coined "the

magical Negro") is not the only example of racist imagery

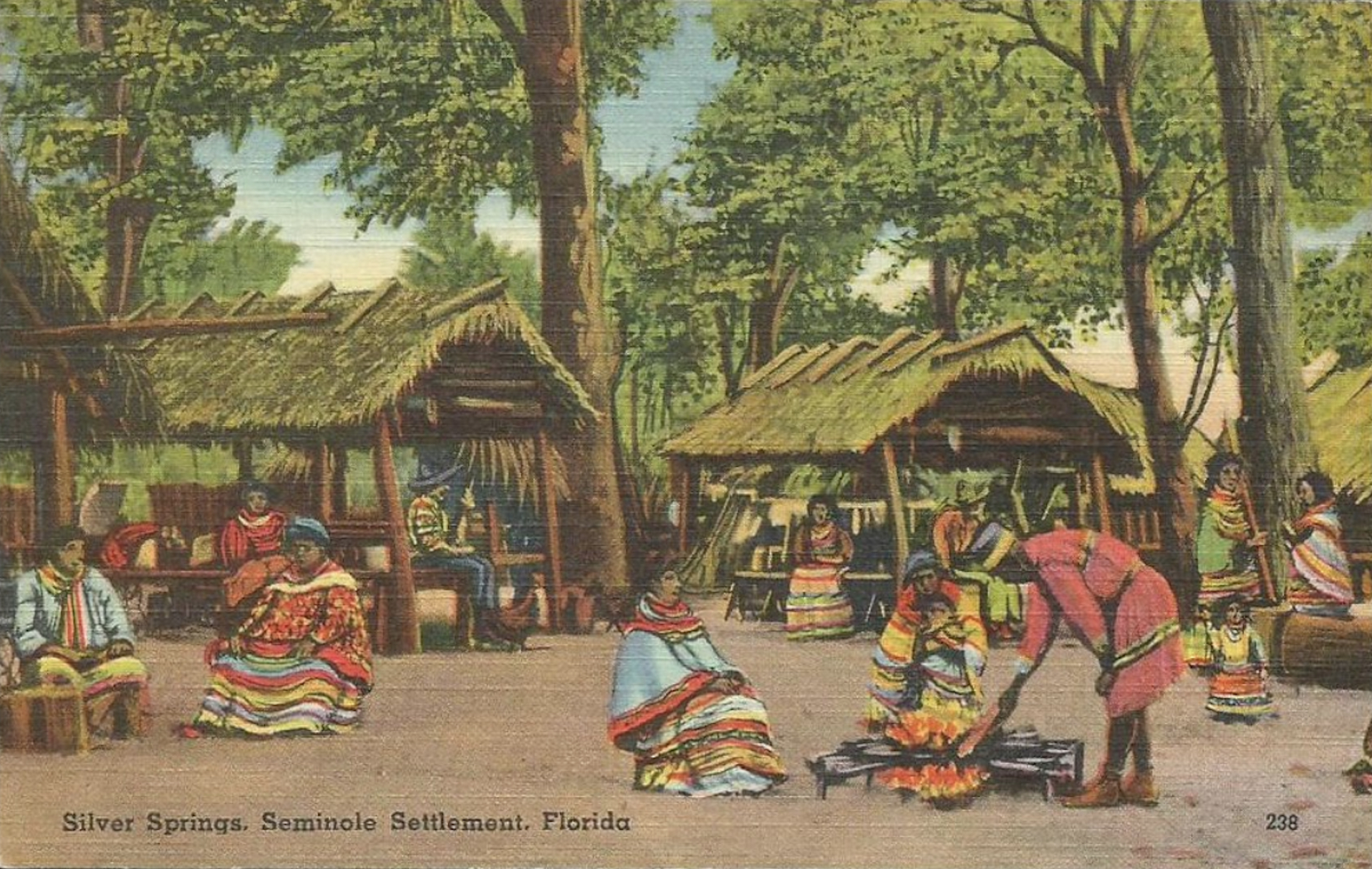

in Silver Springs promotion, past and present (see Figure 5).

Women and minorities are most often shown in servant roles or

as park attractions. African Americans, for instance, were smiling

servants (glass-bottom boat captains) or minstrel performers.

On Emancipation Day 1949, Silver Springs even opened Paradise

Park, a segregated Silver Springs "for colored people" only

(see Figure 6). Seminole Indians were often featured as alligator

wrestlers and colorful, picturesque natives living in the domestic

realm of the Chickee (see Figure 7). The tale

of the ill-fated love affair of Chulcotah and Winona still told

today, however, illustrates the continued presence of Native-American

and gender stereotypes at Silver Springs.11

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Technological

Vision: Science, Power, and the Sublime

Ironically, the exotic characters, danger, and excess illustrated

in the ill-fated love stories so often told by Silver Springs

tour guides starkly contrasts with the controlled experience and

relatively homogeneous riders depicted in the park's glass-bottom

boat promotion. The promotional rhetoric of Silver Springs and

the glass-bottom boat embody the tension between the total abandon

of sublime experience and the positions of power and containment

that often appear in American conventions of sublime representation.

As travel scholar Chloe Chard contends, "The sublime entails

not only a disruption of the state of immobile contemplations,

but also a re-imposition of that state" (137). The 1930s

promotional brochure exemplifies the magisterial gaze that is

part of the representation of Silver Springs as a sublime landscape.

Signifying the sublime experience as often realized in Romantic

and American Transcendental conventions, a god-like perspective

similar to the elevated viewpoints repeatedly shown in landscape

oil painting is presented to the reader in the opening paragraph

of the 1930s Silver Spring brochure:

Picture if you will a palm-fringed strip beside a lake of sapphire

blue giving rise to a river of sparkling transparency and you

have a birds-eye view of Silver Springs; but the water is blue

only when viewed from a distance, for its crystal depths when

seen from the surface are so clear that every fish and aquatic

plant is an open-sesame.

As Allan Wallach asserts, in the conventions of travel literature

established by James Fenimore Cooper, Washington Irving, and Nathaniel

Hawthorne, "The tourist climbs to the top of a mountain,

hill or tower – confronts a panoramic landscape – first overhauled

by feelings of sublimity" (82). The "birds-eye view

of Silver Springs" presented to the reader provides the

expected panoramic vision so often associated with the sublime

as experienced by tourists. Reminiscent of the Romantic landscape

tradition, the omnipotent view allows the reader "to see"

the spring in its entirety: "Navigable to its very source

and fed by innumerable smaller springs, each a gorgeous beauty

spot in itself, the stream meanders through forest primeval to

join the Oklawaha nine miles away."

Not only is the reader given a "birds-eye view" of the formulaically

beautiful "palm-fringed strip" and "sapphire

blue" surface of Silver Springs, but a panoramic view of

the "crystal depths" below the surface is also revealed.

Instead of looking down into the valley atop a mountain-ridge

(like the romantic figures of Durand), Silver Springs's

visitors experience the sublime through glass-bottom boats that

make visible everything underwater. The tourists stare down from

above, through the glass and "sparkling transparency"

of the water, at the sublime landscape below the subterranean

river's surface. From the omnipotent perspective of the

tourist, "every fish and aquatic plant is an open-sesame."

The concluding paragraph even suggests that the mysteries of nature

are revealed in all their beauty at Silver Springs. Nature is

no longer "nature." Instead it is a theater, a panorama,

an invisible place made visible:

Glass bottom boats ply over Florida's Subaqueous Fairyland.

The underwater scenery is as gorgeous and varied as terrestrial

plant and animal life is multiple; for here at Silver Springs

Nature has drawn aside the curtain of mystery that shrouds other

waters and revealed the living panorama of a world unknown to

those who have never seen beneath its surface.

Cultural critics Mary Louise Pratt and Allan Wallach have examined

the power and conventional beauty intimated in omniscient views

like the one constructed for modern tourists in the quoted Silver

Springs description. In the groundbreaking text Imperial Eyes:

Travel Writing and Transculturation, Pratt contends that

nineteenth-century travelers often used promontory views with

pictorial conventions to present themselves as a "discoverer"

who has the power/authority to evaluate, if not to possess, a

scene (205). In his 1993 essay, "Making a Picture of the

View from Mount Holyoke," Wallach uses the term "panoptic

sublime," to describe issues of power and control he sees

in the Romantic visions of Nature. Wallach argues that the omnipotent

panoramic position of vision seen so often in Romantic and Transcendentalist

landscape painting correlates to the surveying control described

by Foucault. In the nineteenth century, only the ruling class

had the time and money to tour because of the expense of transportation

and travel. Wallach writes, for example, "Having reached

the topmost point in an optical hierarchy, the tourist experiences

a sudden access of power, a dizzy sense of having suddenly come

into possession of a terrain stretching as far as the eyes could

see" (83). And in the panorama, the

viewer is shrouded in darkness, invisible, surveying and psychologically

taking possession of all that is laid before him. Like the "open-sesame"

and "living panorama" of Silver Springs, nineteenth-century

panorama paintings, according to Wallach, present the world in

the "form of totality; nothing seems hidden to the spectator,

looking down upon a vast scene from its center, appears to preside

over all visibility" (82).12 Using Pratt and Wallach's thesis, the "birds-eye view" of

nature written into the 1930s Silver Springs brochure and created

by picture frame glass-bottom boats located at the park, not only

reflects the Romantic aesthetics and values of the old genteel

culture but also they offer the tourist the invigorating experience of

possession and power over terrestrial and aquatic nature.

The supremacy of vision and genteel notions of the sublime and

beautiful expressed within the Silver Springs brochure's

Romantic rhetoric are also intertwined within the scientific gaze

connoted in the very design and experience of the glass-bottom

boat itself. In many ways the frame and transparent glass of the

boat's bottom, in which the world below the surface is even

more clearly made visible, functions much like the transparent

lens of a microscope. Like a variety of technologies of observation

that were invented and perfected during the period between the

early Renaissance and the nineteenth century, the microscope made

objects that were invisible visible. These optical technologies

revealed an overwhelming vision of a vast and intricately beautiful

view of the cosmos (both micro and macro). The relationship between

the individual and larger natural systems highly influenced Transcendentalists

like Emerson's concepts of the sublime as revealed by science.

As Wilson contends, "Under the scientific gaze, organisms

become pattern of holistic force, energy, life; an insight into

the relationships between part and whole becomes sublime vision"

(10). Inducing an aspect of the sublime reported by some of its

visitors, the scientific gaze inherent in the glass-bottom boat,

like that of the microscope and telescope, reveals more clearly

the overwhelming depths and biology of the diverse aquatic "universe"

below the Silver River's surface. The text of the 1930s

brochure, for example, rather flamboyantly boasts that the transparency

at Silver Springs "has drawn aside the curtain of mystery

that shrouds other waters and revealed the living panorama of

a world unknown to those who have never seen beneath its surface."

Similarly, Emerson once stated when speaking of the night sky,

"One might think the atmosphere was made transparent with

this design, to give man, in the heavenly bodies, the perpetual

presence of the sublime" (15).

The vision of the sublime constructed for Silver Springs tourists

by the transparency of the water and the scientific gaze connoted

within the frame of the glass-bottom boat has, in many ways, more

in common with representations of the panoptic sublime as discussed

by Wallach. Unlike the eye level sunsets and upward reaching mountains

created by Romantic painters like Casper Friedrich, the glass-bottom

boat riders are situated high above the vast caverns, jutting

rocks, exotic plants, and abundant fish of the Silver River that

they are watching. Like the amateur naturalist travelers examined

by Pratt, they examine the natural world through the privileged

"lens" of science. Although elements of the sublime

(i.e. anxiety-inducing vertigo, disorientation from movement,

and insignificance in relation to the vastness of the depths of

the water) are present, the scientific gaze and the sense of the

picturesque created by the frame of the glass-bottom boat functions

to contain and manage the experience of nature. Like the canvases

of nineteenth-century Transcendentalist American landscape oil

paintings or the outer edges optical devices like the Claude Glass,

the "picture window" of the glass-bottom boat functions

to contain and mediate the experience of the vastness of natural

landscapes. As Neumann argues in relation to the optical devices

and park-sanctioned Kodak photo spots made available at the Grand

Canyon by the National Park service, "The general view of

the Grand Canyon is so overpowering that separating a section

of it for a moment and making it a 'framed picture'

– brings it better within one's comprehension"

(152).

Cinematic

Vision: Nature and Technology Hollywood Style

As our Silver Springs tour nears completion, our captain slowly

turns the boat around and heads back to the Victorian dock. This

time, however, the boat travels northward, tracing the opposite

side of the bank. During the trip home, the captain boasts about

Silver Springs's cinematic history. He instructs all passengers

to look at the right bank in order to catch a glimpse of a horseshoe-shaped

"lucky palm" where movie stars such a Frank Sinatra,

Dean Martin, Doris Day, and Don Johnson got their picture taken

while at Silver Springs. The captain reminds everyone not to forget

to get his or her picture taken there before leaving the park.

"Make sure to make a wish," he adds. The boat momentarily

stops. As the boat hovers, the captain says that he would like

to introduce us to the Silver Springs's celebrities in permanent

residence. After instructing everyone once again to look down

through the frame of glass embedded in the boat's hull,

he points to white, fiberglass statues and states that they were

featured players in the television shows I Spy and Sea

Hunt and in several James Bond feature films. As the boat

begins to move again, the captain recommends that everyone take

the Jungle Cruise glass-bottom boat in order to see the set of

Johnnie Weismuller's television program Tarzan

and the film sets of Marjoire Kinnan Rawlings's novels The

Yearling and Cross Creek.

The moving images created by the frame of the glass-bottom boat

and the passivity of viewers sitting and watching sections of

the world below float past place the natural world within the

culturally sanctioned aesthetics of science, the sublime, and

the picturesque – and is not unlike watching a film. As

Walker Percy asserts, "The very means by which the thing

is presented for consumption, the very techniques by which the

thing is made available, as an item of need-satisfaction, these

very means operate to remove the thing from the sovereignty of

the knower" (62). Jonathan Crary too points out that "technologies

of vision not only suspended the coordinate of a lived time and

space, they equally implicated the spectator in a real and fictional

landscape of successive images effortlessly moving across the

eyes" (158). Anthony D. King also explains, "The window...in modern times functions as a mechanism for consuming the

landscape not only visually (as is the 'picture window')

but also economically and socially" (136).

Conclusion

Influenced by the fact that his Florida essays were part of a

series about the social and economic conditions in the post-Civil

War South commissioned by Scribner's Monthly, Edward

Smith King writes about a Silver Springs that is a peaceful, harmoniously

beautiful, Edenesque garden. While still maintaining some elements

of the sublime, King frames Silver Springs as picturesque by evoking

the Romantic pastoral conventions like the wandering poet or painter,

the prelapsarian landscape, stylized foliage, and a highly aesthetic

setting sun. He writes:

Yes, what of fiction could exceed in romantic interest the history

of this venerable State? What poet's imagination, seven

times heated, could paint foliage whose splendors should surpass

that of the virgin forest of the Ocklawaha and Indian rivers?

What "fountain of youth" could be imagined more redolent

of enchantment than the "Silver Spring," now annually

visited by 50,000 tourists? The subtle moonlight, the perfect

glory of the dying sun as he sinks below a horizon fringed with

fantastic trees, the perfume faintly borne from the orange grove,

the murmurous music of the waves along the inlets, and the mangrove-covered

banks, are beyond words. (145)

Silver Springs as an uniquely American landscape, as a sublime

and picturesque earthly paradise, and the glass-bottom boat as

a privileged way of seeing, all have their roots in European aesthetics

and scientific traditions that attempt to elevate and contain

the natural landscape. By the mid-nineteenth century, Romantic

and American Transcendentalist representations of nature as a

sacred space for transcendence and aesthetic pleasure, which contrasts

against the artificial trappings of industrial civilized society,

became an essential part of the visual paradigm of many upper

and middle class Americans. Thus, the quest for and construction

of the sublime, beautiful, and scientific in nature are often

found throughout the history of American environmental tourist

attractions such as Silver Springs and are inseparably intertwined

with American concerns about national identity, culture, and industrialization.

The construction of Silver Springs as a worthwhile tourist destination,

as an edifying, scientific landscape, as picturesque, as sublime

is illustrated in the nineteenth-century travel narratives of

Daniel Brinton, of Constance Fenimore Cooper Woolson, of George

McCall, in the promotional brochures and souvenir books of the

twentieth century, in the narratives performed by glass-bottom

boat captains today, in the essays of Edward Smith King, within

twentieth-century, park-sanctioned promotional materials, and

through the looking glass in the bottom of the boat itself. Even

today, the rhetoric of Silver Springs promoters not only promises to entertain

glass-bottom boat riders with beauty, motion, and spectacle but

also offers them a scientific education with a sense of national

pride and cultural progress as well. This rhetoric surrounding

Silver Springs is indicative of the larger role tourism and spectacle

play in how Americans define themselves as individuals and as

a nation.

Notes

1. In Florida, later than many destinations on

the American Grand Tour, tourism as an industry did not really

see its modest beginnings as a significant tourist destination

until the region became a territory of the United States in 1821

and a state in 1845. Florida historian Rembert W. Patrick asserts

that it was during the territorial and early statehood periods

that small numbers of visitors/tourists started to replace the

earlier adventurers and journalists who came to Florida. Patrick

further argues that printed journals such as Ralph Waldo Emerson's

Reminiscences, amongst other publications by lesser-known

visiting authors, "were responsible for an ever-increasing

number of visitors who sought the warmth and sunshine of Florida

before the Civil War" (ix). As early as 1869, according

to Patrick, over 25,000 travelers were reported to have visited

Florida; less reliable sources boasted even twice that number

(xiii).

2. According to both the official Silver Springs website and the

Discover Silver Springs: Souvenir Book available today,

it was Phillip Morrell who first invented that glass-bottom in

the late 1870s. But it was not until 1890s that the

glass-bottom boat was commercially developed.

3. John Berger's seminal work Ways of

Seeing first exposed me to this contention.

4. According to John Sears, the American Grand

Tour encompassed the Hudson River, the Catskills, Lake George,

the Erie Canal, Niagara Falls, the White Mountains, and the Connecticut

Valley.

5. Most of the culturally "sanctioned," "certified"

American tourists sights, however, were constructed with little

concern or knowledge of working class or minority tastes and values

until later in the twentieth century. John Kasson, for example,

examines the ways in which the nineteenth-century genteel culture

that dominated early American tourism is eventually subverted

(but never completely) by the more working class aesthetics available

at mass culture entertainment parks like Coney Island and become

even more readily available in the twentieth century. This cultural

shift can also be seen in the snake milking and Alligator wresting

shows that appear in the early 1930s when Ross Allen brings his

"Reptile Institute" to Silver Springs.

6. Sears, Nye, Neumann, and Leo Marx all

examine the importance of Romanticism, nature, and tourism in

the construction of American national identity.

7. The dark color of the Ocklawaha River is attributed

to the tannins present in the water.

8. According to Kenneley's Discover

Silver Springs, the area was designated a Registered National

Landmark in 1925. The U.S. Department of the Interior stated:

"This site possesses exceptional value in illustrating the

natural history of the United States."

9.The brochure was obtained from the Richter Library

of the University of Miami. It is undated. The dress and cars

shown in one of its photographs approximate the date.

10. "Prince Chulcotah, son of Chief Yemassee,

fell in love with Winona, daughter of Ikehumpkee, and enemy chief.

When Winona's father learned of her desire to marry the

prince, he declared war on Yemassee's tribe. Prince Chuloctah

was killed, causing Winona great grief. The story says she lost

her will to live, and on a clear, moonlit night, leapt into the

water and was drowned," read the contemporary Discover

Silver Springs guidebook (Kenneley 14).

11. I have yet to obtain brochures from after

the 1950s; thus, I am not yet certain when the legend changes

in the official guides books. The first glass-bottom boats were

also named after the park founders. My current research includes

discovering when the boat names changed to those of famous Florida

Indians.

12. In the paintings of Casper Friedrich, for

example, the figures most often are positioned at the horizon

even when standing on mountaintops. In many of the Hudson River

School painting, however, the figures are looking down upon the

sublime landscape spread before them.

Works Cited

Allen, Frederick Lewis. Only Yesterday: An Informal History

of the 1920's. New York: Harper & Row, 1931.

Ammidown, Margot. "Edens, Underworlds, and Shrines: Florida's

Small Tourist Attractions." The Journal of Decorative

and Propaganda Arts 23 (1998): 239-259.

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: BBC, 1972.

Brinton, Daniel. Notes on the Floridian Peninsula and Its

Literary History: Indian Tribes and Antiquities. 1859. New

York: AMS Press, 1969.

Chard, Chloe. "Crossing Boundaries and Exceeding Limits:

Destabilization, Tourism and the Sublime." Ed. Chloe Chard

and Helen Longon. Transports: Travel, Pleasure, and Imaginary

Geography, 1600-1830. New Haven and London: Yale UP, 1996.

Crary, Jonathan. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and

Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: MIT Press,

1990.

Davis, Susan. Spectacular Nature: Corporate Culture and the

Sea World Experience. Berkley: U of California P, 1997.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. The Collected Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Nature: Addresses, and Lectures 1. Cambridge: Belknap Press

of Harvard UP, 1971.

Gannon, Michael. Florida: A Short History. Gainesville:

UP of Florida,1993.

Jansen, Partricia. Wild Things: Nature, Culture, and Tourism

in Ontario 1790-1914. Toronto: Toronto Press, 1995.

Kasson, John. Amusing the Million: Coney Island at the Turn

of the Century. New York: Whill & Wang, 1978.

Kenneley, Frances. Discover Silver Springs: Souvenir Book.

Ed. Daniel Le Blanc. Florida Leisure, Inc, 1994.

King, Anthony D. "The Politics of Vision." Understanding

Ordinary Landscapes. Ed. Paul Groth and Todd W. Bressi. New

Haven: Yale UP, 1997.

King, Edward Smith. "The Southern States of North America:

Florida." The Florida Reader: Visions of Paradise from

1530 to the Present. Eds. Maurice O’Sullivan and Jack

C. Lane. Sarasota: Pineapple Press, 1991. 144-148.

Marx, Leo. The Machine in the Garden; Technology and the Pastoral

Ideal in America. 1964. New York: Oxford UP, 1998.

McCall, George A. Letters from the Frontiers. 1868. Gainesville:

U of Florida P, 1974.

Neumann, Mark. On the Rim: Looking for the Grand Canyon.

Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1999.

---. Personal interview. 20 Oct. 2002.

Nye, David. American Technological Sublime. Cambridge: The MIT

Press, 1996.

Patrick, W. Rembert. Introduction. Guide to Florida.

By "Rambler." Gainesville: U of Florida P, 1964. vii-xix.

Percy, Walker. The Message in the Bottle: How Queer Man Is,

How Queer Language Is, and What One Has to Do with the Other.

New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1975.

Pratt. Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation.

New York and London: Routledge, 1992.

Sears, John. Sacred Places: American Tourist Attractions in

the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 1989.

Silver Springs. University of Miami Richter Library Special

Collections, undated brochure.

Wallach, Allan. "Making a Picture of the View from Mount

Holyoke." Ed. David Miller. American Iconology: New

Approaches to Nineteenth-Century Art and Literature. New

Haven: Yale UP, 1993.

Wilson, Eric. Emerson's Sublime Science. New York:

St. Martin's Press Inc, 1999.

Woolson, Constance Fenimore. "The Oklawaha." 1875.

Old Florida 100. Ed. Skip Whitson. Albuquerque: Sun Publishing

Co., 1977.

Wordsworth, William. "The Recluse." Wordsworth's

Poems. Vol. 3. Ed. Philip Wayne. London: J. M. Dent &

Sons LTD, 1955.

|

Back to Top

Journal Home

AmericanPopularCulture.com

|

|