|

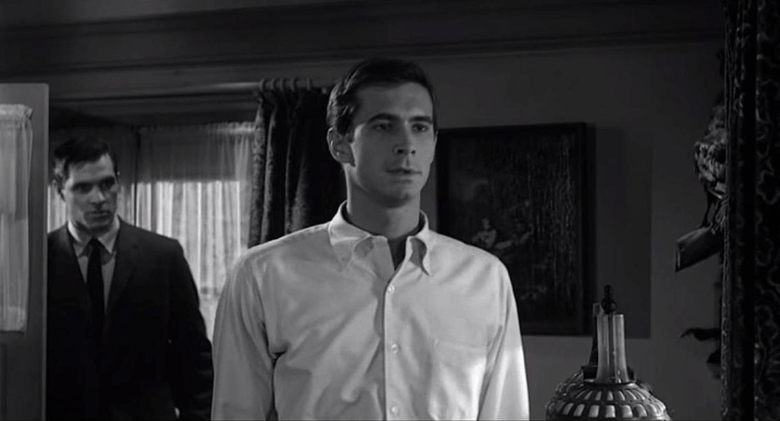

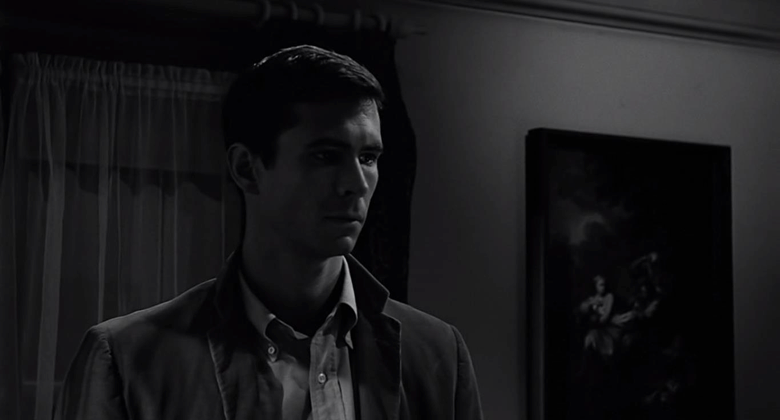

In the original 1960 trailer for Psycho, Alfred Hitchcock notifies us that the parlor of the Bates Motel was Norman Bates' (Anthony Perkins) "favorite spot," then suggests that we visit the parlor with him. Once there, he points to a painting on the wall and says "This picture has great significance, because…" before lowering his eyes and changing the subject, leaving his audience to wonder what, if any, the great significance may be. The image is a copy of the 1731 painting Susanna and the Elders by Willem van Mieris (see Figure 1), and the placement of the object itself is significant to the narrative of Psycho since it covers the hole through which Norman spies on Marion Crane (Janet Leigh). At the same time, the story of Susanna and its depictions in art have intertextual ramifications that extend in many directions, connecting this painting, and the other paintings in the parlor, with the characters and events in the film. For centuries, paintings of Susanna and the Elders have subtly played on the sympathies of viewers, inducing them to identify both with Susanna and with the Elders. By placing this painting so prominently in this scene, Psycho picks up this complicated identification of the spectator as it manipulates its own audience into identifying with both Norman and Marion. In the paintings and in the film, viewers find themselves identifying with both victim and perpetrator in acts of gendered violence.

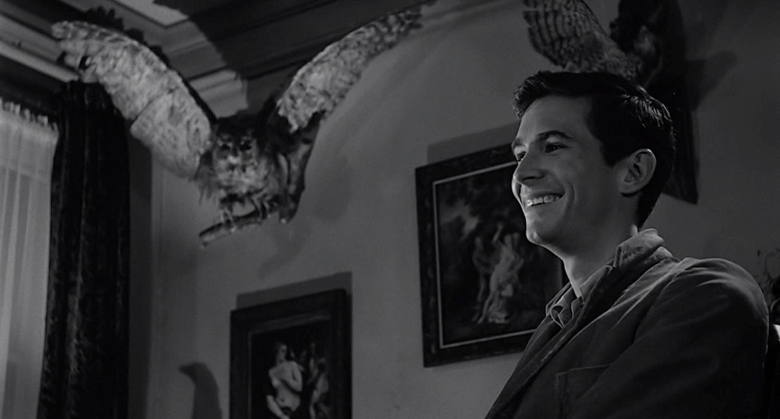

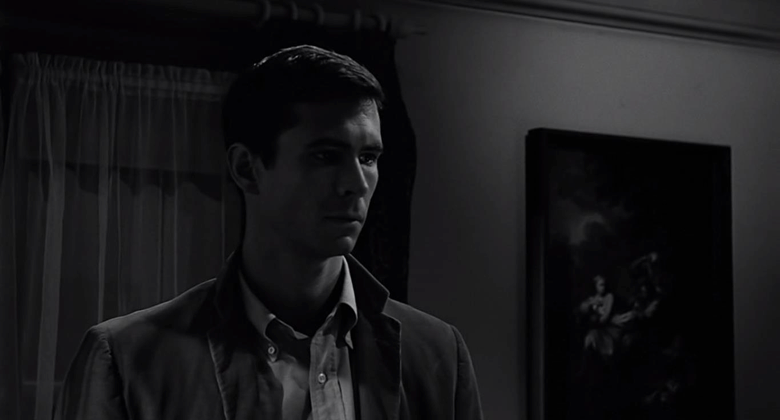

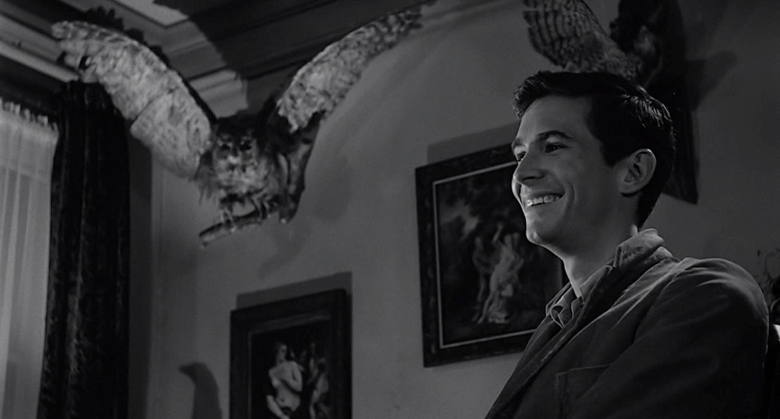

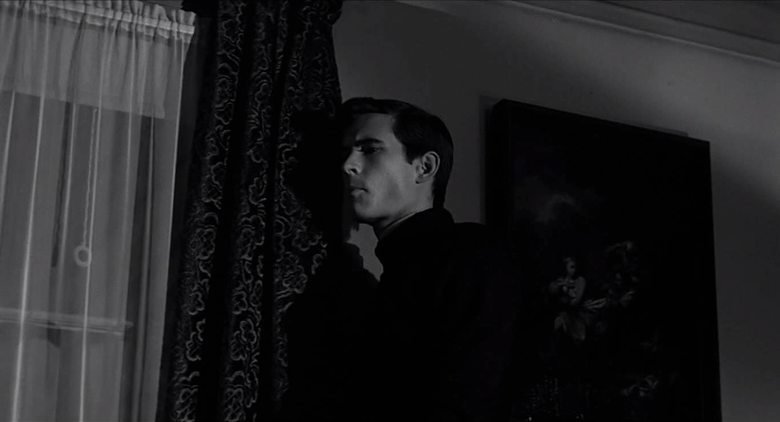

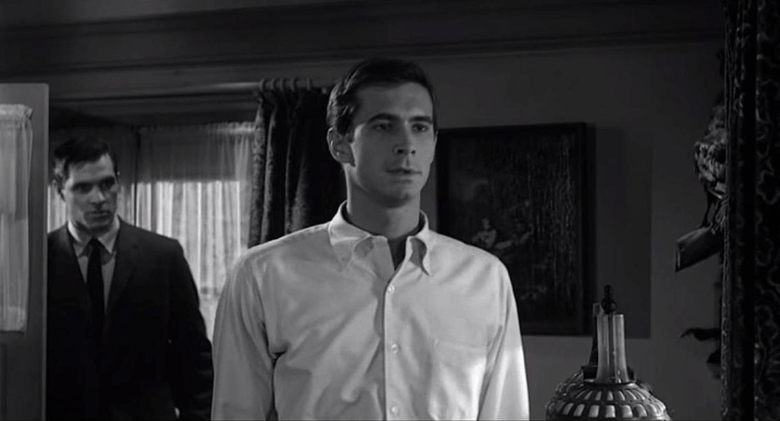

After Marion arrives at the Bates Motel, Norman brings her some sandwiches and milk then invites her into the parlor behind the motel’s office. Norman steps into the dimly lit parlor carrying the tray, which he sets down before switching on a lamp. In the doorway, Marion casts mildly surprised glances at the stuffed birds mounted high on the walls. The paintings in the parlor do not capture her or the camera’s prolonged attention, but they remain in the background in this scene and others. While Norman and Marion are talking, the camera cuts from him to her and back, never showing both of them in the same frame. Behind Norman, we see an owl perched menacingly in the corner. Beneath the owl and somewhat overshadowed by it hangs a small framed painting, which we never see close up and which has received much less critical attention than the Susanna painting has (see Figure 1). William Rothman does not attempt to identify this painting, but observes that "the nude in the painting on the wall is Marion’s stand-in in this frame [which] will be confirmed when Marion strikes that figure’s exact pose" (283). After she has finished eating, Marion holds her left arm diagonally across her chest, as we can see the woman in the painting is doing. While Rothman notes this figure's pose but does not offer any interpretation of it, Neil Hurley sees the woman's crossed arm as a pudica gesture: "On the wall is a picture of a nude woman modestly wrapping her arms around her body in a protective gesture; Marion is seen with one arm similarly gripping her other arm in a subconscious posture of self-defense" (240). Marion may be feeling defensive, but the woman in the picture is making this gesture for other reasons.

Figure 1

The picture behind Norman, next to the Susanna, is a copy of Titian’s Venus with a Mirror, now in the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. (see Figure 2). In Titian's painting, Cupid holds up a mirror as Venus poses, smiling with satisfaction at her reflection. Another Cupid figure reaches out to Venus from behind the mirror to lay a crown of flowers on her head. Venus is wrapped in a sumptuous red velvet cape bordered with fur and extravagant gold and silver embroidery, which covers the lower half of her body but appears to have fallen off of her right shoulder, leaving her torso bare. She holds her left hand up to her chest, perhaps to admire the gold bracelet and ring that adorn it, and check to see how well they go with her pearl earrings and the gold and pearl decorations she wears in her blonde hair. Venus's crossed arm is neither shielding her nudity nor defending her, but is striking perhaps one of many poses as she contemplates her own loveliness. Her posture is reminiscent of the Medici Venus and the Capitoline Venus, both copies of Praxiteles' ancient Venus Pudica statue, in which Venus uses her hands to cover her nudity from the eyes of an unknown observer. Thus the painting not only connects Marion to an idealized vision of feminine beauty, but also alludes to the relationship between Venus and Cupid, an ambiguously sexual mother-son relationship parallel to the one Norman is describing to a disquieted Marion. Later, we will see a small statue of cupid in the foyer of the Bates house.

Figure 2

When the parlor conversation begins, we see Norman from the front, more or less from Marion's point of view. After Norman has finished his speech about private traps, Marion glances toward the house -- in the direction of the Venus, but without seeming to see it -- and says: "If anyone ever talked to me the way I heard…" For the first time, we see Norman in profile as he listens. He is leaning forward, blocking the Susanna with his torso, so that we can only see the Venus in front of him as he expresses his frustration with his mother. He says he would like to leave her forever, or at least defy her, then pauses and leans back, revealing the Susanna behind him. "But I know I can't," he concludes. Marion asks him why he doesn't go away, and he inquires whether he should seek a private island, like her. "No," Marion replies, setting down her sandwich and folding her left arm across her chest, "Not like me."

Even as the audience reflects on Marion's secret, her journey, and her possible repentance, Norman sees her as a reflection of the ideal of feminine beauty that hangs on his wall. George Toles has commented on "the omnipresence of mirrors and reflections in Psycho. Beginning with Marion's decision to steal forty thousand dollars, which she arrives at while looking at herself in the mirror, almost every interior scene prominently features a mirror that doubles as a character’s image, but that no one turns to face" (134). In the painting, Venus is looking at herself in a mirror. As Norman looks at Marion, he sees his images of Venus and Susanna reflected in her, or projected onto her. Norman has been looking at these paintings for years, during the solitary hours he has presumably spent in the parlor, arranging his stuffed birds and peeping on previous guests. As Hitchcock told us in the trailer, it is his favorite spot. He's not looking at the painting of Venus in this shot, but he is looking at Marion, casting his gaze -- freighted with the remembered image of this painting -- in her direction. Perhaps unconsciously reacting to his gaze, heavy with the reflections of these symbolic images, Marion crosses her arms, hugging herself protectively. Later, in the shower, she will strike a pudica pose reminiscent of many Venuses and Susannas as she folds her left arm across her chest, trying to shield herself from her attacker and also, conveniently, shielding her breasts from the viewer.

Titian's image of Venus is reflected again in the painting hanging on the wall next to it, which the viewer of the film sees only when Norman leans back with his resigned, "But I can't." This painting depicts the story of Susanna and the Elders, as many critics have concurred. The story of Susanna, found in Chapter 13 of the Book of Daniel in the Catholic Bible and as Susanna in the Apocrypha, tells of a beautiful, married woman who was in the habit of walking in her garden, as two elders of the community would watch her in secret. One hot day, she decided to take a bath, and sent her maids inside to get oil and ointment. Seeing that she was alone, the two elders came out of their hiding places and threatened to blackmail her if she did not give in to their sexual demands. Susanna cried out for help, and her servants came running, only to hear the elders claim that they had caught her committing adultery with a young man, who had escaped. Susanna was convicted of this crime and sentenced to death by stoning, but young Daniel stood up at her trial and proved that the elders were lying. Her death sentence was then transferred to them.

Many scholars of Psycho have pointed out some of the important allusions that the painting makes. Donald Spoto, for example, underlines the connection between voyeurism, desire, and violence in both the painting and the film: "And so that we have no doubt about his intention, Hitchcock makes everything clear: Norman removes from the wall a replica of 'Susanna and the Elders'…Norman, in other words, removes the artifact of deadly voyeurism and replaces it with the act itself. So much for ‘mere' spying" (322). That this "artifact of deadly voyeurism" has been hanging in the parlor of the Bates Motel for some time suggests that it indicates some predisposition in Norman, as the uninitiated viewer will not fully understand until the end of the film. But there are further connections, as Erik Lunde and Douglas Noverr observe: "Indeed, a close reading of the Biblical story from the thirteenth chapter of the Book of Daniel reveals several themes elucidated in Psycho: voyeurism, wrongful accusation, corrupted innocence, power misused, secrets, lust and death" (101). Citing this passage from Lunde and Noverr, Michael Walker argues: "I would focus, rather, on the significance of the painting for Norman. The voyeurism theme is certainly relevant, but in the original story Susanna resists their sexual assault…it would be more accurate to describe the painting as depicting a rape fantasy, a fantasy which is unfulfilled; hence its particular relevance for Norman" (327). Thwarted rape is, in fact, the central event of the Susanna story, though it has often been euphemized as an "attempted seduction," and many painters preferred to depict a moment of voyeurism rather than a physical attack.

In the Bible, the elders try to extort sex from Susanna by threatening a false accusation that will lead to death for her and dishonor for her family. Therefore, as Jennifer Glancy has shown, "their very real threat of force defines their action as attempted rape, not attempted seduction" (289). The Bible does not mention any physical contact taking place between the elders and Susanna. This part of the story states the following: "When the maids had gone out, the two elders got up and ran to her. They said, ‘Look, the garden doors are shut, and no one can see us. We are burning with desire for you; so give us your consent, and lie with us'" (Susanna 19-21). The passage only gives the words spoken between the elders and Susanna, so it is left to the reader to imagine whether or not some degree of contact occurred at the same time.

The numerous versions of Susanna painted in Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries can be divided into two basic categories: those in which the elders spy on Susanna as she is unaware of their presence, and those that depict some moment after the elders have approached her. Those in the latter category can then be arranged along a scale of degrees of violence: there are many in which the elders are merely talking to Susanna as she listens, others in which they are rushing toward her and reaching out for her, and still others in which they are grabbing at her, pulling away her clothing and assaulting her quite forcefully. The Susanna painting on Norman’s wall would occupy a position toward the more violent end of this spectrum, serving as a subtle warning to the audience that Norman’s voyeurism will have a violent end (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Italian Renaissance paintings of the story tend to be tranquil and pastoral, often showing the elders spying on an oblivious Susanna. As the Baroque style became widespread in the seventeenth century, the theme of Susanna and the Elders remained popular but took a turn toward the dramatic and tenebrist, with wild elders emerging from deep shadows to grapple with a Susanna who struggles against them, her body and garments twisting attractively as they do in the version on Norman Bates's wall. Roland-François Lack identified this Susanna as a 1731 canvas by Willem van Mieris, formerly housed in a museum in Perpignan but stolen in 1972 (n.p.).

The violence in Norman's Susanna prefigures his impending violence against Marion, while Susanna's nudity prefigures Marion's own. However, the Bible indicates that the elders approached Susanna as soon as she had announced her intentions to take a bath to her two maids, and thus would not have had time to disrobe or actually begin bathing. Of course, the mere mention of a bath opened a window of opportunity that Renaissance artists would exploit as fully as possible, or as Tom Gunning puts it, "the theme also provided a religious alibi for painting the nude in the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries" (28). Ellen Spolsky concludes that the bath never happens in the Bible, but that it is "the painterly parallel of Susanna's own desire to bathe in the heat of the day, and the Elders' wish-fulfillment slander. The story spoke clearly to them [i.e. the painters] of the enjoyment of a woman's body, of the lust of the eyes, and they represented it as they saw it in the mind’s eye" (115). The idea that Susanna actually took a bath and that the elders spied on her as she was bathing has become the version of the story most people know, or what Alice Bach terms the doxa. As Bach explains: "By doxa I mean one's idea of a narrative plot point or character or place from some remembered version of it, such as thinking that Delilah cut off Samson’s hair…Often the doxic version becomes cultural baggage for the reader, setting up assumptions that blind one to what appears in the actual text" (4). The doxic version of the Susanna story is the one depicted in many paintings, that she was nude and in the bath as the elders spied on her or approached her.

While the Biblical text does not clearly justify painting a nude Susanna, the early modern art market did. Mary Garrard explains a further dimension of appeal that the story offered:

Few artistic themes have offered so satisfying an opportunity for legitimized voyeurism as Susanna and the Elders. The subject was taken up with relish by artists from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries as an opportunity to display the female nude…with the added advantage that the nude’s erotic appeal could be heightened by the presence of two lecherous old men, whose inclusion was both iconographically justified and pornographically effective. (149-150)

Many popular paintings depict Susanna as bathing in a lush garden while the elders are hidden among the foliage, creating a tranquil, pastoral scene in which the viewer of the painting may identify with the elders and their desire to sneak a peek at the lovely Susanna. An especially famous version of the scene by Tintoretto, now in Vienna, is emblematic of these erotically charged Renaissance Susannas (see Figure 4). Garrard notes that "Tintoretto…offers a representative depiction of the theme in his emphasis upon Susanna's voluptuous body and upon the Elders’ ingenuity in getting a closer look at it" (150). The notion that the (presumed heterosexual male) viewer of the paintings is expected to see himself in the elders and thus feel some kind of empathy for them, although they are the villains of the story, is one that will resonate especially deeply in Psycho.

Figure 4

In Tintoretto’s image, Susanna sits poolside, one leg languorously dangling in the water as she smiles into a mirror. She is surrounded by jewelry, combs, perfume, and luxurious fabrics, and her blonde hair is pulled into an ornate, pearl-festooned arrangement. Spolsky points out the significance of these items: "In the paintings by Tintoretto…for example, the presence of conventional references to Venus (mirrors, jewels, peacocks, cupids), suggests that the beauty of the woman be read as mitigation of the Elders' crime" (102). Tintoretto's Vienna Susanna bears an especially strong resemblance to Venus in the Venus with a Mirror painted by Tintoretto's fellow Venetian, Titian, a copy of which hangs adjacent to Norman's Susanna. Indeed, in Tintoretto's painting, Susanna's mirror is propped against the hedge that one of the elders is hiding behind. As he pokes his head surreptitiously around the corner, he echoes the figure of Cupid in Titian's painting, holding the mirror up so Venus can admire herself.

As mentioned, many painted Susannas of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries seek to delight the heterosexual male viewer by inviting him to see himself in the elders' position as voyeur, simultaneously making this intrusion seem less heinous by presenting Susanna as passive, or even willing. Giving attributes and postures of Venus to Susanna enhances this effect. Garrard observes that Rembrandt's 1647 version of the story, in Berlin, is more sympathetic to Susanna’s plight, "Yet even Rembrandt implants in the pose of Susanna, whose arms reach to cover her breasts and genitals, the memory of the Medici Venus, a classical model that was virtually synonymous with female sexuality" (153). If Susanna is "virtually synonymous with female sexuality," then how can anyone expect the elders not to spy on her? The paintings in the parlor scene in Psycho reconnect Venus and Susanna, positioning Marion Crane as the third vertex in a triangle. Like Venus, Marion holds her arm diagonally across her chest; like Susanna, Marion is spied on and then attacked as she washes herself. Like both, she is desirable, which the psychiatrist at the end gives as the explanation for the crime perpetrated against her. In European paintings of the early modern period, both Venus and Susanna are almost always depicted as blondes, which underlines their visual symmetry to Marion and many other Hitchcock heroines/victims.

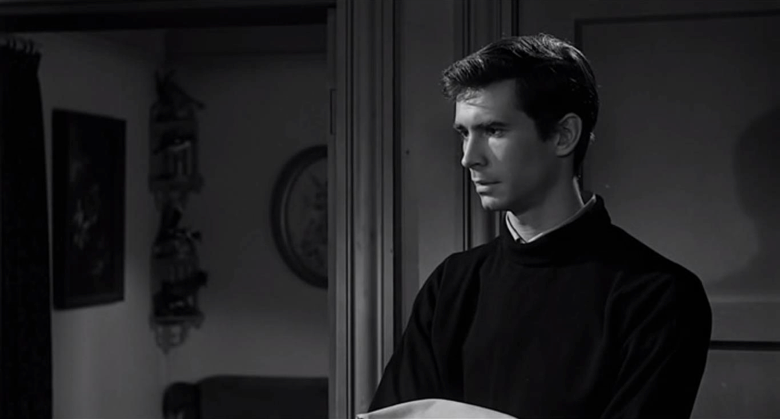

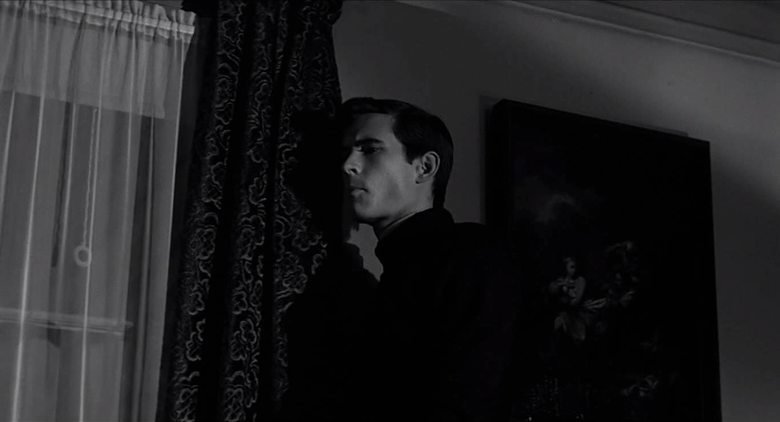

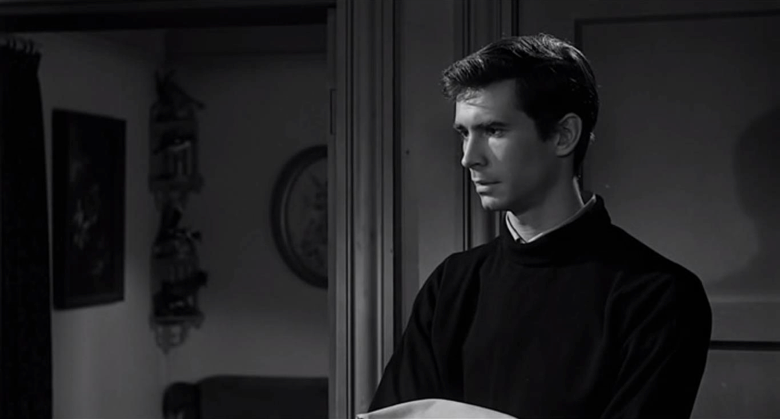

The connection between Venus and Susanna is reinforced by the doubling of these two figures in two other paintings in the parlor. There appears to be a second Susanna hanging on the parlor wall opposite the Venus with a Mirror and the van Mieris Susanna. I have not been able to identify this extremely tenebrist version, though it bears a resemblance to Susannas by Anthony van Dyck and Mattia Preti. We first see this painting after Marion leaves, when Norman goes to the office to check the alias with which she signed the register, then steps back into the parlor (see Figure 5). We see the second Venus only when Arbogast (Martin Balsam) briefly inspects the parlor alone: it hangs next to the door that leads to the office (see Figure 6). This painting is only seen fleetingly, but the composition evokes the central part of Botticelli's Primavera, depicting Venus and the Three Graces. Interestingly, this painting remains the only one we ever see in the frame with Arbogast; the private detective is not subjected to a visual association with the elders, as Norman repeatedly is.

Figure 5

Figure 6

While Norman and Marion are talking, we first see Norman in profile as he leans forward in his chair, and we see only Venus. When he leans back, revealing the Susanna image, this action suggests a progression from the Venus (serene, static, admiring herself in the mirror) and the Susanna (turbulently assaulted, still able to assume an attractive contrapposto in her distress). Female beauty can exist at peace so long as it remains unseen by unpredictable masculine energies, but once that happens, violence seems to be a natural part of the sequence. Raymond Durgnat cites Hitchcock as having a similar attitude toward the disruptive powers of feminine beauty: "As Hitchcock once said, 'A beautiful woman is a force for evil.' She may not be evil in herself, but male sexual desire is, and she can't help provoking it. She's the innocent cause of evil in others" (80). At the end of the film, the psychiatrist says, "He killed her because he desired her." This connection between feminine beauty and male violence against it underlies the entire tradition of Susanna paintings.

When Norman first enters the parlor, however, the camera follows him as he crosses in front of the Susanna first, then bends down to set down his tray and turn on the lamp. As he bends, the Venus becomes visible behind him. He first goes quickly from Susanna to Venus, but then we see the paintings in the reverse order, more slowly, as he is sitting and conversing with Marion. After she retires for the night, the camera focuses on the Susanna for one moment, before Norman removes it to watch Marion undressing. As David Greven observes:

The story is overdetermined as a Hitchcock motif, containing, as it does, so many of his signature themes. There is a long tradition in Western visual art of reading this biblical narrative as a rape scene, and this painting joins the number of classical rape paintings that adorn the back wall of Norman’s office, all of which signal the history of anti-woman violence, and that this hideous history is being made in the present. (97)

The Bible is ambiguous as to whether or not there was any physical contact between the elders and Susanna before she cried for help, thwarting any attempt they may have made to rape her by force rather than by coercion. There is no ambiguity, however, about the fact that they carry out the threat they made to her, accusing her of adultery and testifying to it at her trial, willing to see her executed for this imaginary crime once she had spurned their advances. Marion has refused Norman’s request that she remain in the parlor "just a little while longer, just for talk," and a moment later he spies on her and then, like the elders, unleashes violence against her.

Psycho echoes both the voyeurism and the misogynistic violence referred to in the Susanna story, but Norman's use of it as the screen that hides his peephole makes the voyeurism connection especially sly, as Tom Gunning points out: "The congruence between the painting’s subject and the use Norman Bates puts it is so exact that it strikes one as a Hitchcockian joke" (28). Joseph Stefano's screenplay calls for the parlor to be decorated with "paintings…nudes, primarily, and many with a vaguely religious overtone" (n.p.), but does not specify Susanna. When Norman removes a picture from the wall, the screenplay only says "a picture" (n.p.). Art director Robert Clatworthy recalled that Hitchcock was "far more finicky about odd unsettling details of decor -- such as the kitschy sculpture of hands folded in prayer in Mother’s room -- than with the structures themselves. Crucial for Hitchcock, too, were the sets for Norman's parlor behind the motel office, the bathroom, and Mother’s room" (Rebello 95). It seems likely, then, that the inclusion of only images of Susanna and Venus -- doubled ones at that, echoing the many other doubles in the film -- rather than any other vaguely religious nudes that might have been chosen was indeed Hitchcock’s joke, and not anyone else's.

Gunning analyzes the relationship between Norman's voyeurism and his violence against Marion:

We know from the subsequent actions that his vision has excited not only his lust but also his guilt and impulse toward punishment, triggering the murder of Marion, punishing her for a sexual titillation entirely due to Norman’s own voyeurism (like the plot of the Elders against Susanna). Thus guilt and violence of the sort depicted in the painting serve as a screen to block and transform the image of desire, a visual filter that darkens and perverts the sexual impulse. (29-30)

The Bible plainly states that Susanna's beauty is the cause of the elders' crime: "Every day the two elders used to see her, going in and walking about, and they began to lust for her. They suppressed their consciences and turned away their eyes from looking to Heaven or remembering their duty to administer justice" (Susanna 8-9). This scene in Psycho tells a similar story, using the Susanna painting as a metonymy: Marion is beautiful, Norman wishes to see more of her, so he peers illicitly through the wall; as a result, he is so inflamed with desire that he acts recklessly and violently against the woman he desires. As Gunning observes, the art serves both to hide the act of voyeurism and to twist it into something more sinister.

That a work of art could inspire and motivate a man’s desire is an idea with a long history. Lynda Nead summarizes several accounts of men lusting after art:

There are a number of myths, which are frequently recirculated, concerning the stimulating effects on male viewers of nude female statues and paintings. In his Natural History Pliny describes an assault on Praxiteles’ statue of Aphrodite of Cnidos. It seems that a young man had become so infatuated with the statue that he hid himself one night in the shrine and masturbated on the statue…In another permutation of this fantasy of male arousal there is the case from sixteenth-century Italy, of Aretino, who so admired the exceptional realism of a painted nude Venus by Sansorino that he claimed "it will fill the thoughts of all who look at it with lust." Over two centuries later, there is the example of the bibliophile Henry George Quin, who crept into the Uffizi in Florence when no one was there, in order to admire the Medici Venus and who confessed to having "fervently kissed several parts of her divine body." (87)

As Nead observes, in the Pliny and Quin examples, the covert aspect of the man's access to the art enhances his excitement: "The excitement is produced, partly at least, by the transgression of and deviation from norms of public viewing and by the relocation of the work of art within the realm of the forbidden" (88). Norman uses his van Mieris Susanna to shield his realm of the forbidden, but also draws strength from it to perform forbidden actions: after he spies on Marion, we see him in profile and can only see the edge of the painting’s frame as he rehangs it on the wall. Then he looks at the image for a moment before glancing ominously toward the house. Norman has transferred his illicit desire for the Venuses and the Susannas onto the real person Marion Crane; the painting has given him courage to peep in the first place, and now the combination of the painting and his real life voyeurism have inspired him to do violence against her.

The trope of a work of art depicting violence against women being seen as an inspirational precedent is quite ancient. In Terence's comedy The Eunuch, Chaerea disguises himself as a eunuch in order to gain access to prohibited spaces and be close to Pamphila, the girl he desires. Later, he recounts to his friend Antipho how seeing a painting strengthened his resolve to assault the girl:

Presently they made preparations for her bath. I urged them to hurry. While things were being got ready, the girl sat in the room, looking up at a painting; it depicted the story of how Jupiter sent a shower of gold into Danae's bosom. I began to look at it myself, and the fact that he had played a similar game long ago made me all the more excited: a god had turned himself into human shape, made his way by stealth to another man's roof, and come through the skylight to play a trick on a woman…Was I, a mere mortal, not to do the same? I did just that -- and gladly. (379-381)

The story Terence evokes is that of Zeus and Danaë, in which the latter’s father locks her in a tower to protect her virginity, but Zeus visits her in the form of a rain of gold. Whether or not Danaë is a willing participant in this union is unclear, though Renaissance paintings tend to depict her as quite receptive to the arrival of the rain. Danaë, Susanna, Bathsheba, Venus, Lucretia, Diana, and Actaeon, along with a few other stories from antiquity, were considered in the Renaissance to offer legitimate pretexts for painting female nudes. In Chaerea's account, delivered to his friend after the fact, he does not describe the painting, so the audience can only wonder if Danaë showed any resistance in the image. It is clear, however, that Pamphila did resist: a woman in the household later complains that "the villain ripped her whole dress and tore her hair" (387) and "the girl is crying and doesn't dare say what happened when you ask her" (387). This description reveals that Chaerea has perpetrated a violent rape, although by his own account he merely "play[ed] a trick on a woman" (379). The play in general characterizes him as an immature rascal who learns responsibility by marrying his victim, rather than as a vicious criminal who merits punishment.

Like Chaerea, Norman's lust is excited by a painting, and it encourages him in his transgressions. Like Susanna, Danaë, and Pamphila, Marion thinks that she is shielded by the walls of her private space, but a woman's private space is subject to intrusion by men who see their desire for her as a justification for their invasion of her privacy. Terence's audience has little chance to identify with Pamphila, who has no lines in the play. In Psycho, at the time that Norman spies on Marion through his Susanna-defended peephole, we have just met him as a character while Marion has been, for forty-five minutes, the heroine of the film.

At the moment of her death, Marion extends a hand in search of support before collapsing in the shower. Toles analyzes the shocking effect on the audience of the loss of her as a main character: "Marion’s gesture to save herself answers our felt need [that she survive], then instantly turns that need against us. Part of Hitchcock's complex achievement in the film is gradually to deprive us of our sense of what 'secure space' looks like or feels like" (120-121). The audience thought that they were safe in identifying with Marion, just as Marion thought she was safe in Cabin One. But as the Susanna paintings in the parlor have warned us, the prying eyes of men will seek out beautiful women wherever they go -- they do not really have any safe and private spaces. Hitchcock pulls the entire audience into this sense of insecurity, thrusting them into a vulnerability parallel to Marion's at the same moment that he leaves them no choice but to now identify with Norman.

This switch of audience identification from Marion to Norman has been much discussed. Robin Wood describes the spectator's sense of disorientation at the moment of her death: "so engrossed are we in Marion, so secure in her potential salvation, that we can scarcely believe it is happening; when it is over, and she is dead, we are left shocked, with nothing to cling to, the apparent center of the film entirely dissolved" (146). As Philip Skerry points out, throughout the Bates Motel scene, between Marion's arrival and her murder, the camera gradually switches to Norman's point of view (173), preparing the audience to identify with him after her abrupt departure from the story. As Norman spies on Marion getting undressed, Skerry continues, "Hitchcock kindly allows the audience to spy with him" (175). Hitchcock, like the Renaissance painters of Susanna, depicts a scene of voyeurism and invites the viewer to join in, assuming the voyeur’s point of view -- and expects viewers to react to this "kindness" with gratitude.

Joseph Smith notes that the peeping scene "serves as an effective link between the two halves of the film…it's our first opportunity to observe Norman alone, and thus to begin identifying with him. Yet like our identification with Marion, the connection we feel with Norman is troubling. As Norman watches Marion undress, we watch too, and thus we share his guilt" (67). Smith continues, "Hitchcock accentuates the culpability of viewers -- or at least of those viewers who are male -- by cutting away just as Marion is about to remove her brassiere" (68). The assumption that the heterosexual male viewer sees himself in the voyeur is a central feature of the majority of paintings of Susanna and the Elders, particularly those that depict a voyeuristic scene before the elders approach Susanna. By placing the two Susannas in the parlor, Hitchcock has added a layer of assistance to help his viewer see himself in Norman.

Even in the original Biblical tale of Susanna, as Amy-Jill Levine argues, the text forces readers to identify with the elders. The character of Susanna, she writes, is "compromised by the elders' desires. For the story to function, their desire must be comprehensible to the reader, and thus Susanna must be a figure of desire to us as well. And once we see her as desirable, we are trapped: either we are guilty of lust, or she is guilty of seduction" (313). This victim-blaming aspect of the original story -- that Susanna's beauty was the cause of her misfortune -- was exploited to its fullest potential by painters in the early modern period, luring the viewer of the painter in to the perspective of the elders. Spolsky observes that one of the elders often holds up a shushing finger, "extended toward the viewer, as if to say 'Don't disturb her' -- and at the same time, 'Don't be so quick to judge us -- wouldn't you also be enchanted by her?'" (102). This same shared culpability is exploited in Norman's peeping scene in Psycho and implemented to steer the viewer toward identifying with him. Much as Norman sees the elders in his painting as a mirror of himself, the viewers of Psycho now see themselves reflected in Norman.

Hitchcock takes this point to an extreme close-up during the scene in which Norman spies on Marion, just after removing the van Mieris Susanna from the wall. As he peers into Marion's brightly lit room, a beam of light from the peephole illuminates his face. We see a close-up of his eye from the side, the light shining into it as he watches her. First, we see Marion tossing aside her blouse, standing in the black bra and half-slip we saw her wearing in her room in Phoenix, just after deciding to steal the money. We see her as if through the peephole, but the camera cuts away just as she reaches to remove her bra: now we see only Norman's eye for a moment, before cutting back to his view as she wraps a robe around herself. Here the film pushes the limits of what can be tolerated by a mainstream audience. Psycho cannot show Marion naked, but it makes clear that Norman has seen her so, and it invites its audience to envy him. Skerry analyzes this important moment:

Norman has seen Marion naked; he has seen what no audience for a commercial film had seen up through 1960. This extraordinary situation of having a character not only see what an audience cannot in the diegesis of the film, but also see what an audience could not in the extra-diegetic world of cinema in general, is unique in Hitchcock’s oeuvre. In this subscene, Norman is the principal viewer, but what he sees cannot be shown to us. (119)

During this scene, the camera cuts back and forth between a Norman's-eye view of Marion, and views of Norman's eye itself. This intercutting allows the audience not only to identify with Norman but also to fill in the gap of what he is seeing that cannot be shown. In the Susanna paintings where she is unaware of the elders' presence, the painters included the elders so that the audience could identify with them and take pleasure in knowing that they were seeing something they were not allowed to see. In Psycho, Norman actually sees what the audience cannot be allowed to see. Instead, we gaze upon his single, fascinated eye for this one moment.

In the scene in which Norman spies on Marion as she undresses, Psycho uses the montage technique to splice out her contextually inevitable nudity, substituting a brief shot of Norman's eye in such a way that the audience imagines what he sees. In the murder scene, Hitchcock further assaults Hollywood's Production Code, using montage to suggest images of both violence and nudity without actually showing either. Hitchcock's masterful use of editing makes this possible, as Skerry observes:

This kind of scene construction and editing [i.e. in which violence is suggested but not shown] had evolved over the years, and directors had utilized these techniques to circumvent the Code by suggesting violence and by transferring the action to the mind of the spectator. Eisenstein had perfected this technique in his theory and practice of montage: shot A + shot B (both on the screen) = shot C (in the mind of the audience). (7)

Sergei Eisenstei's theorization of montage technique was not concerned with avoiding showing violence. Eisenstein and other early Soviet filmmakers had set out to understand how the art of the cinema worked, and they had reached the conclusion that film editing was the one quality that was unique to cinema. Eisenstein observed that the proponents of montage had "discovered a certain property in the toy [i.e. film editing] which kept them astonished for a number of years. This property consisted in the fact that two pieces of film of any kind, placed together, inevitably combine into a new concept, a new quality, arising out of that juxtaposition" (4, emphasis in original). He gives examples of combinations of words, images, or ideas that create associations or new concepts when they are combined, arguing that this idea is not new in the cinema nor unique to it. For instance, if we see a grave and a woman weeping, we assume that she is the widow of the man buried there (4-5). In montage, Eisenstein continues, "Piece A (derived from the elements of the theme being developed) and piece B (derived from the same source) in juxtaposition give birth to the image in which the thematic matter is most clearly embodied." Expressed in the imperative, for the sake of stating a more exact working formula, this proposition would read: "Representation A and representation B must be so selected from all the possible features within the theme that is being developed, must be so sought for, that their juxtaposition -- that is, the juxtaposition of those very elements and not of alternative ones -- shall evoke in the perception and feelings of the spectator the most complete image of the theme itself" (11, emphasis in original).

In Eisenstein's breakdown of the idea, the "image of the theme itself" or image C, the abstract concept that the filmmaker wishes to get across to his audience, is best created in the mind of the spectator. This way, spectators can tailor their own "image of the theme itself" according to their own perceptions and experiences. In Eisenstein's famous Odessa steps montage in Battleship Potemkin, the juxtaposition of (A) mercilessly firing troops and (B) suffering people are meant to create an image (C) of the injustices of capitalist imperialism. Shot (C) is the goal of the film, but it does not exist in it anywhere. Rather, viewers construct it in their minds.

In the shower scene in Psycho, Skerry explains that the carefully crafted juxtaposition of very short pieces of film create a terrifying montage: "Hitchcock prided himself on not actually showing the knife stabbing Marion. He claims that the violence occurs inside the viewer's mind (shot C, in the Eisensteinian sense). He also claims that the nudity is equally suggestive, never explicitly shown" (11). Unlike the class struggle in Battleship Potemkin, the knife entering Marion’s torso is not too abstract to film, as the hundreds of slasher films released since Psycho have demonstrated. The Production Code prohibited it, however, and Hitchcock's pride in not showing it might stem in part from his use of montage to cleverly sidestep the Code's restrictions. In his interview with Skerry, screenwriter Joseph Stefano says: "I asked [Hitchcock], ‘How will you get that across? The knife goes like this, and then we cut to a fake wound?’ And he said, ‘Oh no, no. We don't need any of that. This is a murder that is taking place in the audience's mind, and it should be just a flash'" (56). In addition to any concerns he may have had about the Code, Hitchcock appears to have also felt pride that, by leaving the stabbing unseen, he was forcing the viewers to create a more terrifying vision in their minds.

Hitchcock's shower scene went against the precepts of the "Hollywood montage" (Dmytryk 135) that was prevalent in classical studio films. The Hollywood style evolved to favor editing that reduced the story to its essence in a way that flowed smoothly for the viewer. Ken Dancyger explains that early directors "discovered that it isn't necessary to show everything. Real time can be violated and replaced with dramatic time" (350). Dancyger gives an example of how dramatic time can be employed in a film to avoid wearying the audience with a scene of a character traveling. Instead, she will be shown departing, then "the editor then cuts to a street sign or some other indication of the new location" (359). This type of montage sought to present seamlessly a narrative that allowed the viewer to suppose what happened during unseen intervals. Instead of shot (C) being an abstract or unshowable concept as in the artistic Soviet montage, in the Hollywood montage shot (C) consists of narrative details with which the viewers need not concern themselves. As Skerry tells us: "Hitchcock once said that cinema was life with the boring parts left out" (143). The process of splicing together shots filmed at different times and in different places is unique to film, but the idea of streamlining a narrative to boil it down to its most compelling elements is far older than cinema.

As I discussed earlier, the Bible's description of the story of Susanna does not directly refer to Susanna disrobing or getting into the bath. It merely states that (A) the elders were watching her and that (B) Susanna decided to take a bath. To borrow Eisenstein's terminology, the juxtaposition of these two details "evoke[d] in the perception and feelings" (11) of many Renaissance painters the alluring image (C) of a seductive, Venuslike Susanna bathing as the elders watched her. While the Biblical story leaves out the details to keep the story moving, in the Hollywood sense of narrative economy, the image of a bathing Susanna is shot (C) in the Eisensteinian sense. Similarly, the violent paintings in which the elders assault her show a scene that is neither described nor contradicted in the Bible; they were assembled in the painters' minds based on detail (A) the elders went up to her and (B) they demanded that she satisfy their desires. Given these facts, the extrapolation that (C) they ripped off her clothes and physically assaulted her will naturally emerge as the "image of the theme itself" (Eisenstein 11) in the minds of many readers.

These details, so lavishly embellished by so many generations of painters, are missing from the Biblical account in such a way that they are neither explicitly there nor impossible to imagine. They do not appear to be narrative lacunae to the reader of the Book of Daniel or the Apocrypha's Susanna; the narrative flows smoothly and briskly, squeezing a great deal of drama and tension into a compact tale. A precise description of the movements of Susanna and the elders at every moment would transform this gripping whirlwind into a tedious slog. The story's original creators eliminated details in the interest of dramatic time -- creating a smooth, Hollywood montage of the essentials of the story. But painters reinterpreted the elision of detail -- creating a vast lacuna of detail in their minds, inserting a shot (C) that stretched the likelihood of what (A) and (B) appeared to suggest. The universal association born of juxtaposition that Eisenstein described became either a pastoral voyeurism fantasy or a rape fantasy.

In the novel by Robert Bloch on which Psycho is based, the character of Marion is named Mary, and her death happens in one sentence. Toles examines how Hitchcock’s film adaptation gives this event center stage: "Is Marion’s shabby, useless death a proper occasion for a virtuoso set piece? Surely an abbreviated, less conspicuously artful presentation would honor the victim more, if the meaning (in human terms) of what transpired figured at all in the artist's calculations" (128). Even if Psycho has no moral as such, a young woman's sudden death still means something, and the film distracts us from this by showing us a dazzling work of art.

In a similar way, Tintoretto's breathtaking Susanna draws us in with its luminosity and makes us forget what the story was about. As Garrard observes: "Even when a painter attempted to convey some rhetorical distress on Susanna's part… he was apt to offset it with a graceful pose whose chief effect was the display of a beautiful nude" (150). Garrard argues that the pleasure agenda of the male artists and their male patrons overwhelmed the meaning of the Susanna story, and the female painter Artemisia Gentileschi was the only one to identify with Susanna rather than the elders. In Psycho, the audience has identified with Marion up until she is murdered, but her murder in the center of the film forces them to begin to identify with Norman.

As I discussed above, Psycho's audience already began to identify with Norman during the voyeurism scene. The success of this is demonstrated by how many male film scholars express envy of Norman’s ability to watch as Marion removes her underwear. After Marion dies, the viewers of the film do not know to whom they should cling. In his interview with Skerry, screenwriter Stefano says: "After the shower scene we've lost the person that we were with, that we identified with, that we cared about. Remember, we didn't want that cop to arrest her. We wanted her to get away with the money. W'’re all such felons at heart" (55). Stefano believes that the audience's desire to identify with the protagonist is stronger than any desire they are likely to have to identify with justice and the law. Stefano says he told Hitchcock, "At that time [i.e. after Marion's death], the movie is over unless we get the audience to care about Norman" (55). Several new characters, notably Marion's sister Lila Crane (Vera Miles), are introduced in the second half of the film, and Marion’s boyfriend Sam Loomis (John Gavin) reappears. Though Sam and Lila could have the potential to become our new protagonists as they investigate Marion's disappearance, the audience has already latched on to Norman.

Seeking to make the audience care about Norman, Stefano reports that it was his idea to include Norman's lengthy cleaning up sequence after the murder, recalling times in his childhood when he was forced to clean up after his alcoholic father (55). In Spoto’s account of viewing the film, Stefano's technique is effective: "Just as we have conflicting feelings about Marion…so we have divided feelings about Norman. He does such a first-rate cleanup of Mother's messy murder, doesn't he, and with him we’re ever so relieved when Marion's car, which was momentarily stuck in the swamp, finally sinks with a septic gurgle" (320). Watching the premiere of the film with his wife, Stefano says that he heard the audience gasp when Marion's car stopped sinking. He turned to his wife and whispered: "You know, I got them! They love Norman now. They don't care if he buries her in a swamp" (63).

At this point, as far as the viewer knows, poor Norman is concealing the crime perpetrated by his "ill" but "harmless" mother. Norman's efforts to protect his mother, Wood writes, make it easier for the viewers to shift their identification to him: "Norman is an intensely sympathetic character, sensitive, vulnerable, trapped by his devotion to his mother -- a devotion, a self-sacrifice, which our society tends to regard as highly laudable…He is a likable human being in an intolerable situation" (146). While the viewer may have disapproved of Norman's peeping and wished he had respected Marion's privacy, this infraction is not enough to erase all of the sympathy we feel for his helpless sweetness and his efforts to do the best he can with his awful lot in life. He is himself very attractive, to the extent that a viewer who is attracted to men may find their judgment clouded as the narrative continues to unfold. If the heterosexual man can't blame Norman for being a voyeur, the heterosexual woman really wants him to be as kind and gentle as he seems to be. In any case, we have no choice but to hold on to him, as Skerry explains:

We know from many of Hitchcock's comments about the film that he enjoyed "tricking" the audience into identifying with Marion so that when she dies, we are left hanging, in a sense… Thus, if we accept the notion of identification, which was first discussed in Aristotle's Poetics in the analysis of catharsis, then we can conclude that the killing of Marion creates for the viewer what Ortega y Gasset calls "existential shipwreck." (176)

After a shipwreck, Ortega y Gasset writes, survivors look for something to cling to and will grab at any piece of driftwood they can find (Skerry 176). In Psycho, Skerry continues, this driftwood to which the viewer must cling is "the seemingly innocent, naïve, charming, boyish, and attractive character of Norman. In the cinematic world of the late 1950s, Norman would be the perfect romantic protagonist…It is probably Hitchcock's greatest casting decision to propose Anthony Perkins for Norman" (176). In Bloch's novel, Norman is middle-aged, overweight, and an alcoholic. Hitchcock proposed Perkins for the role, baiting the trap into which the viewer falls by making them like this attractive young man who appears to be awkward but perhaps noble. As Hitchcock himself says in the trailer, "This young man -- you had to feel sorry for him." Perkins's sweet face is hard to resist, especially for first-time viewers who are concerned for him and what his mother appears to be putting him through.

The actor invested careful thought in the role. Stephen Rebello describes how Perkins "developed a powerful affinity not only for the surface behavior of Norman Bates but also for the inner workings. ‘It was my idea to have Norman nervously chewing candy in the film,' Perkins enthused about the character who was to become a national folk antihero. 'He would not plot malice against anyone. He has no evil or negative intentions. He has no malice of any kind'" (118-119).

Rebello's description of Bates as "a national folk antihero" is intriguing. Even among experienced viewers who know who he is, know what he has done, Bates remains a compelling figure. Hitchcock and Perkins so carefully crafted him to be likable that we still like him after we learn the truth, as Smith suggests in his personal anecdote of seeing Psycho III in a theater in 1986: "During the scene in which Norman finally climbs into bed with an attractive woman, one young male viewer called out cheerily, 'Go for it, Norman!' That viewers could still feel this way years after knowing the truth about Bates is ample testament to Perkins's nuanced, sympathetic portrait" (55). Without a doubt, this is true. But it also testament to the dual consciousness produced in the viewer by the original film, evoked by the image of Susanna and the Elders: one feels for poor, innocent Susanna. But one also feels for the elders, whose actions are not quite pardonable, but may be understandable.

Much as Hitchcock elected to cast the charming, handsome young Perkins as Norman, Renaissance painters tended to paint the elders as venerable old men, who seem fairly respectable even as they perpetrate their crime against Susanna. Tintoretto's elders bear a strong resemblance to St. Peter and other esteemed older religious figures who appear in his other canvases. Just as the viewer's shared voyeurism with them made the painting more alluring and the elders more relatable, the elders' appearance as nice, grandfatherly figures makes it difficult to judge them too harshly. In van Mieris' painting, the elders are temporarily disfigured by wanton expressions, and their postures are more openly transgressive than they are in many other Susanna canvases. But the painting's presence in the film carries with it all of the cultural freight of its history, and these ramifications remain on the screen as a result. The audience's identification with Norman parallels the earlier identification viewers had with the Elders. Even if the viewer's sympathies are split between the male violator and the female victim, these two stories form a part of the larger tradition of the perpetrators of violence against women being seen as somewhat sympathetic.

After Norman peeps on Marion and replaces the van Mieris Susanna on the wall, the audience does not see this painting again. The second Susanna, however, continues to haunt Norman from a distance in later scenes: it is seen through the door when Norman is talking to Arbogast in the office (see Figure 7), and again when he hangs up the phone after talking to Sheriff Chambers (John McIntire) while sitting in the parlor (see Figure 8). In these scenes, it is on the wall opposite the other Susanna, perpendicular to the wall separating the parlor from the office. Near the end of the film, it moves and now hangs next to the door when Sam Loomis confronts Norman in the office (see Figure 9).

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Previously, when Arbogast was snooping in the vacant parlor, this same space was occupied by the second Venus; thus, the progression from the ideal of female beauty to the act of violence against it is repeated as the second Susanna takes the place of the second Venus. The second Venus is only seen when Arbogast is in the parlor. Arbogast is never shown in the frame with either of the Susannas; as far as we know, he is not a pervert, and thus he is free from association with the elders. The second Susanna changes position, as though it were insistently inserting itself into the frame with Norman, hounding him, hanging over his shoulder like a guilty conscience.

Like Chaerea in The Eunuch, Norman Bates sees a painting of a woman's privacy being violated and is inspired to violate a real woman's privacy. Like the elders, his desire for a woman converts into an act of violence against her. Whether or not the full cultural impact of the Susanna story was familiar to the audience or the filmmakers of Psycho, it makes the film that much richer and more complex. As Wood writes: "[Hitchcock] himself -- if his interviews are to be trusted -- has not really faced up to what he was doing when he made the film. This, needless to say, must not affect one's estimate of the film itself…Hitchcock (again, if his interviews are to be trusted) is a much greater artist than he knows" (151). Again, Hitchcock cast Anthony Perkins to make it that much easier -- and more perilous -- for the viewer to sympathize with Norman, as well as with Marion. This dual identification with both the victim and the perpetrator is emphasized by the Susanna paintings, linking Norman to the elders, which in turn links him to an expansive artistic and literary tradition that extends across many centuries and cultures. Hitchcock may not have known the full extent of the multilayered connections he was making by including these images, yet they hang on the walls of the Bates Motel, indicating that Norman’s crime is a new manifestation of a much older story.

Works Cited

Bach, Alice. Women, Seduction and Betrayal in Biblical Narrative. Cambridge UP, 1997.

Durgnat, Raymond. A Long Hard Look at Psycho. Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Eisenstein, Sergei. The Film Sense, translated and edited by Jay Leyda, Harvest, 1975.

Garrard, Mary D. "Artemisia and Susanna." Feminism and Art History: Questioning the Litany, edited by Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, Westview Press, 1982, pp. 146-171.

Glancy, Jennifer A. "The Accused: Susanna and Her Readers." A Feminist Companion to Esther, Judith and Susanna, edited by Athalya Brenne, Sheffield Academic Press, 1995, pp. 288-302.

Greven, David. Psycho-Sexual: Male Desire in Hitchcock, De Palma, Scorsese and Friedkin. U of Texas P, 2013.

Gunning, Tom. "Hitchcock and the Picture in the Frame." New England Review, vol. 28, 2007, pp. 14-31.

Hurley, Neil P. Soul in Suspense: Hitchcock's Fright and Delight. The Scarecrow Press, 1993.

Lack, Roland-François. "A Picture of Great Significance: Hitchcock's Susannah." The Cine-Tourist, www.thecinetourist.net/a-picture-of-great-significance.html. Accessed 20 December 2015.

Levine, Amy-Jill. "‘Hemmed in on Every Side': Jews and Women in the Book of Susanna." A Feminist Companion to Esther, Judith and Susanna, edited by Athalya Brenner, Sheffield Academic Press, 1995, pp. 303-323.

Lunde, Erik S. and Douglas A. Noverr. "'Saying It with Pictures': Alfred Hitchcock and Painterly Images in Psycho." Beyond the Stars III: The Material World in American Popular Film, edited by Paul Loukides and Linda K. Fuller, Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1993, pp. 97-105.

Nead, Lynda. The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity and Sexuality. Routledge, 1992.

The New Oxford Annotated Bible, New Revised Standard Version with the Apocrypha, edited by Michael D. Coogan, Oxford UP, 2010.

Psycho. Dir. Alfred Hitchcock. Perf. Anthony Perkins, Janet Leigh, Vera Miles, John Gavin, Martin Balsam. Paramount, 1960. DVD.

Rebello, Stephen. Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho. Soft Skull Press, 2012.

Rothman, William. Hitchcock -- The Murderous Gaze. Harvard UP, 1982.

Skerry, Philip J. Psycho in the Shower: The History of Cinema's Most Famous Scene. Continuum, 2009.

Smith III, Joseph W. The Psycho File: A Comprehensive Guide to Hitchcock's Classic Shocker. McFarland, 2009.

Spolsky, Ellen. "Law or the Garden: The Betrayal of Susanna in Pastoral Painting." The Judgment of Susanna: Authority and Witness, edited by Ellen Spolsky, Scholars Press, 1996, pp. 101-117.

Spoto, Donald. The Art of Alfred Hitchcock: Fifty Years of His Motion Pictures. Second edition. Anchor/Doubleday, 1992.

Stefano, Joseph. Psycho (screenplay). The Internet Movie Script Database, http://www.imsdb.com/scripts/Psycho.html. Accessed 17 December 2015.

Terence. The Eunuch. Terence: Vol. I, translated and edited by John Barsby, Harvard UP, 2001, pp. 314-452.

Toles, George. "'If Thine Eye Offend Thee…': Psycho and the Art of Infection." Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook, edited by Robert Kolker, Oxford UP, 2004, pp. 120-146.

Walker, Michael. Hitchcock's Motifs. Amsterdam UP, 2005.

Wood, Robin. Hitchcock's Films Revisited. Columbia UP, 1989. |