Today, Levittown is a model of diversity, McDonald’s promotes

salads, Kay Thompson’s Eloise turns Disney in a TV movie,

Ford reissues the Thunderbird, and Playboy celebrates its fifty-year

anniversary in good taste. The Senate exhumes McCarthy’s

papers, Elvis impersonators roam wild, Ozzy Osbourne and family

replace Ozzie and Harriet, American Idol replaces The

Ed Sullivan Show, and the Mr. Rogers era is sadly over. With

each nostalgic tribute, reissue, and revision of a bygone era,

the American 1950s looms ever larger than life. The images of

this era are icons of American prosperity and success, particularly

within the context of the home. After all, some of the most significant

events of the 1950s occurred literally in the home, broadcasted

into each family room, living room, or den across the nation.

The living room, to be sure, was a weighted locale—developers

and architects as diverse and as diametrically opposite as William

Levitt and Frank Lloyd Wright marketed their home designs with

emphasis on the central living space, on togetherness.

But let us walk out of the living room, Mr. Rogers’ semi-public

domain, into a seemingly benign space, the American kitchen. The

kitchen can be seen as epitomizing the sacred sustenance of the

family unit. But it can also be considered as the most political

space in the entire home—itself a microcosm of society—in

its relevance to social function and its aesthetics of creation,

preservation, and waste. This paper traces the physical development

of the American kitchen, the significant role of the kitchen in

national and international politics, and the portrayal of kitchens

in various examples of period literature. Ironically, but not

surprisingly, more than just a repository for Jell-O molds and

Lipton’s onion dip, the 1950s kitchen plays a significant

role on both private and public levels, in terms of both national

identity and politics of the marginalized. Assorted historic records

testify to the dogged presence of an alternative kitchen, in which

traditional, stereotypical semiotics of wife, mother, maid, and

Other are subverted.

Figure

1

Figure

1

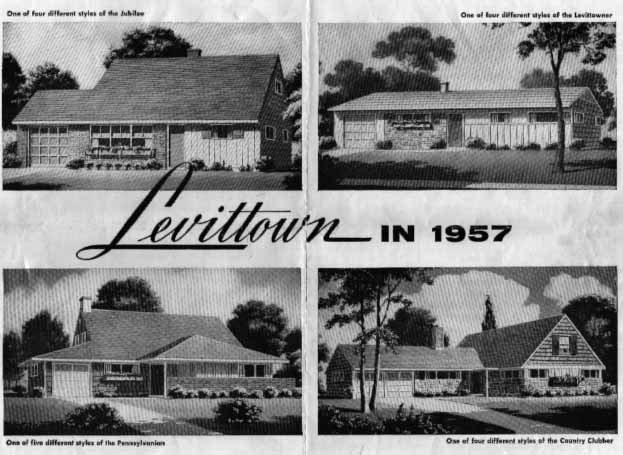

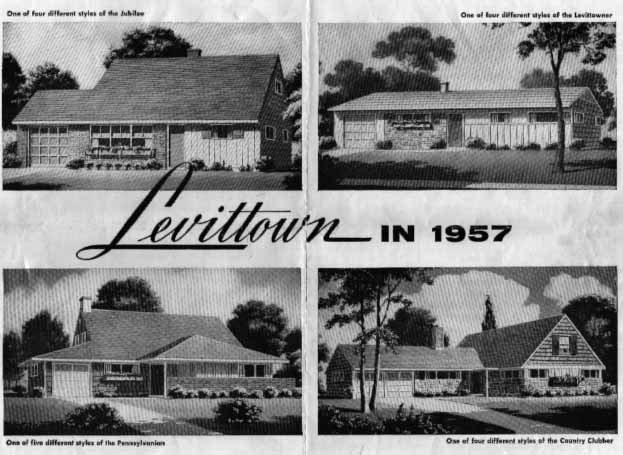

The kitchen of the 1950s was, of course, part and parcel of the

home as a whole. Conflicting styles of architecture and the philosophies

behind them during the period introduced the idea of the home—the

private—as political and public. “The house of moderate

cost is not only America’s major problem but the problem

most difficult for her major architects,” Frank Lloyd Wright

stated in The Natural House (qtd. Rosenbaum 17). In Levittown,

Long Island, in 1947, developer William Levitt sought to solve

this “problem.” Synthetic shingles, plastics, and

adhesives were components of Cape Cod cottages and Ranch houses,

the two categories of houses from which prospective homeowners

could choose. House after house was constructed in uniform, tight

grid format in this new concept of homogeneous American suburbia

(see figure 1). Houses came with televisions already installed,

and furniture arrangement suggestions. Levittown was immediately

billed as the suburban democratic ideal for everybody. But as

Gwendolyn Wright notes in Building the Dream, “Although

dense, multi-use communities clearly represented changes in the

traditional American way of life, they did not, as yet, suggest

the idea that people themselves could direct these changes”

(261). Indeed, as Herbert Gans notes in The Levittowners,

a sociological study of American middle class ways of life, the

town and its contents were planned down to the last detail—from

residents not being allowed to hang particular clotheslines in

their yards, to the initial ban against fences, to racial discrimination.

William Levitt commented:

The Negroes in America are trying to do in sixty years what

the Jews in the world have not wholly accomplished in six hundred

years. As a Jew I have no room in my mind or heart for racial

prejudice. But…I have come to know that if we sell one

house to a Negro family, then ninety to ninety-five percent

of our white customers will not buy into the community. That

is their attitude, not ours…As a company our position

is simply this: We can solve a housing problem, or we can try

to solve a racial problem, but we cannot combine the two. (qtd.

in Halberstam 141)

Here Levitt articulates a disturbing link between politics and

domesticity. He states that Blacks expect too much from society

and should wait their turn for equal rights. The ultimate message

is one of clear discrimination and racism—one subsidized

by the federal government through the GI Bill.

Architect Frank Lloyd Wright, however, conceived very different

notions for Americans’ new quality, cost-effective housing.

Wright applied to the problem his own core principles of architecture:

strong relationship between building and site, simplification

of form, horizontal emphasis, organic architecture, and central

living space. Like Levitt, Wright advertised his idea in terms

of American democratic ideals. He combined the words “utopia”

and “USA” to coin the term “Usonia,” his

vision for moderately priced small houses in suburban American

communities (see figure 2). Usonian houses featured one-story

horizontal plans, open kitchens, central hearths, and window walls.

Flat roofs with large overhangs, unit system walls, and radiant

heat were important components of the Usonian house, which was

typically private and closed to the street, while open to the

garden in the rear of the house. Inexpensive standardized natural

materials were utilized, such as wood, brick, concrete, and glass,

while unnecessary extras like trim, paint, plaster, and decorative

objects were eliminated. Warm tones such as red and gold were

often used on the interiors where built-in furniture coordinated

and conserved space, and freestanding tables, chairs, and stools

had multiple functions. Indirect lighting and simple textiles

contributed to minimal decoration. The extension of the house

to the garden outside through rear open architecture and windowed

walls resulted in the strong interplay of exterior light with

interior space. An additional key to the concept of Usonia was

cooperative community, with shared facilities. Although many Usonian

homes were built, Wright’s larger vision of widespread Usonian

communities was never realized. Only two such cooperative communities

were formed, in Michigan and New York State during the 1940s and

1950s.

Figure 2

Figure 2

In 1947, at the same time Levittown was under construction, Taliesin

apprentice David Henken located a ninety-seven acre site in Pleasantville,

Westchester County, New York, for a cooperative housing project.

His vision was based on Frank Lloyd Wright’s idea of Usonia,

a community of inexpensive, non-elaborate, but tasteful and functional

single-family homes built on circular one acre plots (see figure

3). The Pleasantville community was given the name Usonian Homes

II, with three houses designed by Wright, the majority designed

by Henken himself, and a few designed by other architects. As

Wright declared in The Natural House, “The Usonian

dwelling seems a thing loving the ground with a new sense of space,

light, and freedom—to which our USA is entitled” (qtd.

Rosenbaum 185). Although cooperative land ownership and houses

for fifty families proved unrealistic, a group mortgage with ninety-nine

year leases for the owners, granted by a progressive bank president,

was established in 1947. Usonian Homes II thus became one of the

only applications of Wright’s utopian vision for America,

including design review with shared ownership of property and

democratic community government in a suburb. Usonian Homes II

was the work of a dedicated group of middle-class citizens who

had no formal political agenda but who promoted ethnic and racial

diversity and were interested in an idealized American community—one

that still exists today.

Figure 3

Figure 3

In 1959, in another example of the powerful connotations of domesticity,

the American kitchen burst forth from containment to go on the

road. Conflicting ideas of the domestic and the democratic were

epitomized in 1959 at the Moscow Kitchen Debate during the height

of the Cold War. As Amy Kaplan argues, “The homeland may

contract borders around a fixed space of nation and nativity,

while it simultaneously expands the capacity of the United States

to move unilaterally across the borders of other nations”

(61). Bringing the American home with him, Vice President Richard

Nixon traveled to Russia to debate issues of interior design and

domestic gadgetry with Khrushchev. Nixon declared, “We don’t

think this fair will astound the Russian people, but it will interest

them. To us, diversity, the right to choose, the fact that we

have a thousand different builders, that’s the spice of

life. We don’t want to have a decision made at the top by

one government official, saying we will have one kind of house.

That’s the difference” (qtd. in Halberstam 724). Levitt

claimed, “No man who owns his own house and lot can be a

Communist. He has too much to do” (qtd. in Marling 253).

When Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev visited the United States

during the 1950s, Eisenhower wanted him to visit Levittown.

The American exhibition in Moscow included model homes and kitchens

with the latest technology, American supermarket displays, and

even fashion shows with vignettes from life in the United States.

There were multiple models of sewing machines, hi-fi sets, convenience

foods, twenty-two cars, and a Disney movie theater. Fashion models

enacted American rituals such as weddings, honeymoons, and barbeques.

All of these components, in addition to American corporate buildings

in miniature, advertised the American way of life. There were

emblems of Cold War propaganda and the success of capitalism.

Khrushchev deemed the American exhibition excessive, indicative

of vacuous consumerism. Indeed, American prosperity was extremely

hyperbolized, further so by Russians hungrily ingesting (literally

and figuratively) each icon. Visitors consumed food and free Pepsis

from the supermarket display at the rate of nineteen thousand

per hour for the entire forty-two days of the show. More than

aesthetics, the kitchens represented social values. But if all

aspects of American life could be so easily replicated, including

supposedly meaningful rituals, the authenticity of the original

was doubtful.

Figure 4

Figure 4

The environment of the Kitchen Debates was extremely politically

charged (see figure 4). As Kaplan contends, “The notion

of the nation as a home, as a domestic space, relies structurally

on its intimate opposition to the notion of the foreign. ‘Domestic’

has a double meaning that links the space of the familial household

to that of the nation, by imagining both in opposition to everything

outside the geographic and conceptual border of the home”

(59). While homes and kitchen preferences seemed more benign and

pleasant to debate than nuclear war, they were actually lethal

propaganda weapons. They were intrusion of the highest order,

as they infiltrated the home. Karal Ann Marling writes, “The

American kitchens in Moscow—today’s kitchen and tomorrow’s—provided

a working demonstration of a culture that defined freedom as the

capacity to change and to choose and dramatize its choices in

the pink-with-pushbuttons aesthetic of everyday living”

(283). The actual kitchen debate was only a few minutes long.

Nixon claimed that the cameras happened to be rolling as he and

Khrushchev had a tense exchange, and insisted their dialog was

impetuous, though the lines seem scripted. The following is an

excerpt from a toast that closed the event:

Khrushchev: We stand

for peace [but] if you are not willing to eliminate bases than

I won’t drink this toast.

Nixon: He doesn’t like American wine!

K: I like American wine, not its policy.

N: We’ll talk about that later. Let’s drink to talking,

not fighting.

K: Let’s drink to the ladies!

N: We can all drink to the ladies. (qtd. Marling 280-81)

Here Khrushchev is force-fed American domestic politics in both

senses of the word “domestic.” The political importance

of the kitchen is evident. The men perform well, enacting a drama

of domestic dispute. Ironically, even as women modeled the kitchens,

the toast conveys the fact that women were only significant on

the level of the domestic inside the home, clearly powerless and

irrelevant on a national/international scale. So ended the debate,

with the kitchen epitomizing conflicting philosophies of democracy

vs. communism, choice vs. conformity, and their inversions.

As Ellen Lupton observes, “Although the built environment

is designed largely by men, much of it’s constructed with

female consumers in mind; design thus contributes to the ‘making’

of modern woman” (12). To understand the political intersection

of women and the kitchen, one can examine its history, as well

as its storytellers. In The Kitchen in History, Molly

Harrison makes the following observation:

Social history is inevitably pieced together as a mosaic, and this story of the kitchen, particularly

so. If it seems at some times a repetitive story, at others perhaps

a somewhat contradictory one, the fault lies in ourselves—in

those multitudes of housewives who, by habit or by improvisation,

have worked and planned, laughed and cried and struggled, to feed,

clothe, and bring up husbands and children, look after pets and

entertain guests. We have not created a tidy story or a very logical

one, but we know in our hearts that it has always been important.

(2)

Even as Harrison presents her academic endeavor, she identifies

herself with the “multitudes of housewives”—“ourselves”—who

have functioned solely as mothers, wives, and caregivers in domestic

roles. She apologizes for the lack of a “tidy” or

“logical” story; in doing so she takes away all faculty

of reasoning and analytical ability she (and women as a whole)

may possess. It is unfortunate that a social history of the kitchen

begins by both negating the toil and sweat associated with the

room, as well as the intellectual capacity of the gender typically

aligned with it. In a markedly different view regarding conventional

domestic roles for women, Carolyn G. Heilbrun notes:

The threshold was never designed for permanent occupation…those

of us who occupy thresholds, hover in doorways, and knock on

doors, know that we are in between destinies. But this is where

we choose to be, and must be, at this time, among the alternatives

that present themselves. And homely or beautiful, real or surrogate

mothers, married or unmarried…we are today, as Adrienne

Rich expressed it, finding our way to read and to rewrite “the

book of myths/ in which/ our names do not appear.” (101-102)

Heilbrun alludes to the historically liminal roles women play

in the theater of advancement. Her use of Rich’s words from

“Diving into the Wreck” illustrate the ambiguity and

duality of the patriarchal myth, its power to historicize, its

doubtful content, and the absence of women in both. The notion

of the “threshold” speaks to the Janus ambiguity of

the 1950s kitchen.

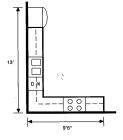

Figure 5

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 6

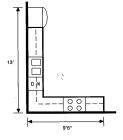

With the mass migration to the suburbs, many new kitchens were

built during the 1950s (see figures 5 and 6). The U- and L-shaped

kitchen plans were popular, with smaller variations for smaller

houses and apartments. Kitchen trends included movement away from

bright, primary colors for appliances and décor towards

pastels and softer colors, workspace “island” counters,

and focus on the sink, stove and countertop triangle of convenience.

1950s stoves featured double ovens and high backsplashes (though

washable wall materials were popular, too). Countertops were often

constructed of linoleum. General Electric issued its spacemaker

refrigerator in the early 1950s, a fridge with magnetic doors

in 1956, and the first rectilinear fridge in 1957. Ninety-degree

angles replaced the rounded curves of earlier refrigerator construction.

Other popular kitchen components included Maytag’s matching

automatic electric washer and dryer, otherwise known as the Supermatics.

The steam iron, coordinated plastic tableware, the electric can

opener, and the four-slice toaster enjoyed increasing favor (Plante

270-74). The planned obsolescence of coordinated kitchen products,

developed in the early 1950s, encouraged women’s spending

and linked design and consumerism. “As objects of emotional

attachment, mechanical devices animate the scenes of daily life,

stimulating feelings of love, possibility, and connection, as

well as guilt, restriction, and isolation. The self emerges out

of material things, which appear to take on lives of their own,”

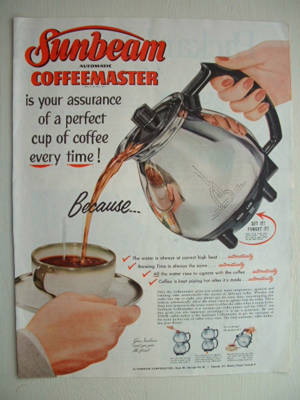

Ellen Lupton states in Mechanical Brides (8). Period

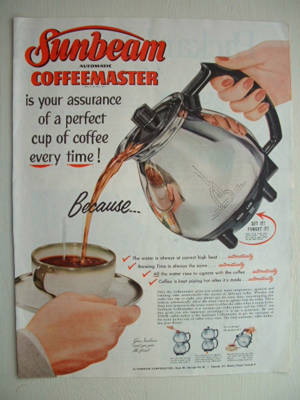

advertisements for kitchen-related products often depicted the

female body itself as a machine with detachable parts, working

to please husband and children. One such example is the Sunbeam

Coffeemaster ad from 1950, in which a disembodied manicured hand

pours coffee for her husband, reflected in the coffee pot looking

nauseatingly condescending (see figure 7). The advertised automatic

features of the coffee machine ensure that the wife/mother does

not have to reason how to make the best cup of coffee.

Figure 7

Figure 7

In a refreshing update to the social history of kitchens and their

frequent inhabitants, Ellen M. Plante explores the relevance of

the feminist movement. Plante notes that while the 1950s and ‘60s

housewives are considered to express the first unified displeasure

at their limited life pursuits, the evolution of the housewife

began in the nineteenth century. Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s

Women and Economics (1898), for example, argues that

women should not exist to serve men and enable their hierarchical

authority inside and outside the home. Gilman suggests that the

large, commercial kitchens and laundry centers should take on

what was traditionally women’s work, thereby emancipating

women from the kitchen and home.

But fifty years later, American women convey dramatically different

views on their roles as housewives. In an August 1950 article

in The Atlantic Monthly, Agnes E. Meyer argues for housewives

to be recognized as integral to the family unit as well as to

society as a whole:

Instead of apologizing for being a mere housewife,

as many women do, women should make society realize that upon

the housewife now fall the combined tasks of economist, nutrition

expert, sociologist, psychiatrist, and educator. Then society

would confer upon the status of housewife the honor, recognition,

and acclaim it deserves. Today, however, the duties of the homemaker

have become so depreciated that many women feel impelled to work

outside the home in order to retain the respect of the community.

(qtd. Plante 283)

In direct contrast, in an article from the year before, “Women

are Household Slaves,” author Edith M. Stern writes:

When a woman marries and has children, it is assumed that she

will take to housewifery…Such regimentation, for professional

or potentially professional women, is costly both for the individual

and society. For the individual, it brings about conflicts and

frustrations…The educated individual should have a community,

a national, a world viewpoint; but that is pretty difficult to

get and hold when you are continually involved with cleaning toilets,

ironing shirts, peeling potatoes, darning socks, and minding children.

(qtd. Plante 285)

The kitchen thereby becomes a battleground with both defensive

and offensive players occupying it. Despite the authors’

distinct viewpoints, each alludes to the kitchen and its products—the

elevated knowledge of “nutrition” vs. the menial task

of “peeling potatoes”—as central to the role

of women. Interestingly, the later article speaks of “women”

and their domestic talents repeatedly, whereas the earlier article

de-sexes the context and refers to the protagonist as the “individual.”

Relevant to this opposition, in 1963, Betty Friedan compiled unwanted

magazine pieces on the state of women in society to produce The

Feminine Mystique. Friedan writes, “It was a strange

stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered

in the middle of the twentieth century…each suburban wife

struggled with it all alone. As she made the beds, shopped for

groceries…chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside

her husband at night, she was afraid to ask…the silent question,

‘Is this all?’” (7). Clearly, the kitchen has

by this time become a problematic, political space that delineates

male and female boundaries and, to many, symbolizes entrapment

and containment. Food and its creation have ominous connotations.

How does art portray life in terms of 1950s domesticity and the

kitchen? It is interesting to examine fictional representations

of the kitchen in period literature. An influential precursor

to 1950s fiction, J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the

Rye (1951) toys with ideals of domestic stability, particularly

in terms of the nuclear family. Holden Caulfield is never at ease

for long within a domestic or surrogate domestic setting. He is

at odds with his boarding school dorm mates, uncomfortable when

a headmaster or teacher attempts to “adopt” him. Leevom

Medovoi argues, “As the reception of The Catcher in

the Rye reveals, cold war intellectual culture authorized

dissent in youth culture by proclaiming—whether for better

or for worse—the quintessentially American character of

idealistic, adolescent rebellion and the fundamentally democratic

character of commercial, mass-mediated forms” (282). The

novel’s “rebellion” and “democratic character”

can be framed in terms of the aversion to the domestic, which

is interesting for two reasons: first, because Holden deems domesticity

“phony;” second, because Salinger equates American

youth with American democracy. Ultimately, in Holden’s eyes,

both notions of “domestic” come up short. Salinger’s

portrayal of the kitchen comes when Holden visits the Antolinis,

old family friends. The Antolinis are initially presented as supposedly

reassuring emblems of intelligence and successful partnership,

but after Holden encounters them in their home, this perception

is destroyed.

“Lillian! How’s the coffee coming?” Lillian

was Mrs. Antolini’s first name.

“It’s all ready,” she yelled back. “Is

that Holden? Hello, Holden!”

“Hello, Mrs. Antolini!”

You were always yelling when you were there. That’s because

the both of them were never in the same room at the same time.

It was sort of funny. (182-83)

Mr. Antolini, highball in hand, surrounded by used liquor glasses

and dishes of peanuts in the living room as he discusses philosophy

and literature with Holden, yells to his wife to check on her

progress with food preparation. Mrs. Antolini, meanwhile, in curlers

and prettifying night gear, remains in the kitchen until breezing

by to go to bed. Before her eventual appearance, Mrs. Antolini

becomes a disembodied voice of the kitchen. Salinger clearly emphasizes

their distinct male and female spheres; Holden even notes that

the couple rarely shares the same room. The Antolinis appear to

be a fairly stereotypical 1950s couple. But the author debunks

this myth when Holden wakes up in the middle of the night, alarmed,

to find Mr. Antolini patting his head. Salinger establishes the

conventional norm of domestic life only to undermine and subvert

it.

Several years later, Sloan Wilson’s The Man in the Grey

Flannel Suit (1955) offers a similar presentation of seemingly

typical domestic life. The title of the novel suggests the anonymity

of the protagonist, but beyond his marriage with children in a

Connecticut suburb and his disheartened commute to New York City

in search of a better job, better salary, and better happiness,

his domestic life is bland, vacuous, and rushed—details

that emerge in the context of the home.

Tom went downstairs and

mixed a martini for Betsy and himself. When Betsy came down, they

sat in the kitchen, sipping their drinks gratefully while the

children played in the living room and watched television. The

linoleum on the kitchen floor was beginning to wrinkle. Originally

it had been what the builder described as a “bright, basket-weave

pattern,” but now it was scuffed, and by the sink it was

worn through to the wood underneath. “We ought to get some

new linoleum,” Betsy said. “We could lay it ourselves.”

(6)

Here there is an interesting departure from the kitchen as a

simply female domain; both husband and wife enjoy their drinks

in the space. The decay of the linoleum floor, however, represents

the decay of their marriage, and the old question mark shaped

crack in the wall serves as a reminder of a past fight and the

consequential inaction to cover the crack. Betsy’s suggestion

regarding the new linoleum recalls the lack of progress on the

earlier proposed project.

Later, after Tom informs Betsy of his illegitimate child in Italy,

they discuss the faults of their marriage, and proclaim their

love for one another. In an amusing reassertion of the 1950s housewife,

Betsy worries, “Do they have trouble getting enough food

and medicine and clothes over there? We should find out what he

needs and send it. We shouldn’t just send money” (272).

Here ideals of femininity and domesticity take an odd turn, as

Wilson inserts them in the context of extramarital sex and helping

an illegitimate child. While the descriptions of kitchens in The

Catcher in the Rye and The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit

begin with male and female norms, they end with subversion

of the those stereotypes, as they introduce, respectively, pedophilia

and extramarital sex. Still, both novels concern Anglo-Saxon characters

in middle to upper-middle class America anxious to ground themselves,

to find comfort in “home.” In contrast, Ralph Ellison’s

Invisible Man (1952) traces an African American protagonist’s

travel around the periphery of domesticity, implying no place

exists for him at the center. Benita Eisler notes, “It was

no coincidence that the exciting new fiction of the fifties took

as its subject the excluded: those outside that magic but elusive

mainstream where we all wanted to be. Marginals, deviants, and

subterraneans were the heroes and heroines of all my high school

non-required reading” (97). The Invisible Man’s protagonist

moves from place to place, confronted by façades of welcome

that eventually crumble. One of the few positive domestically

framed encounters occurs with Mary, his sympathetic landlord,

who is often identified with the kitchen. Despite Mary’s

presence, the kitchen is a poor, destitute environment and offers

little nourishment to the Invisible Man. He describes the kitchen

as reeking of cabbage, which he associates with childhood poverty.

He often declines the food Mary offers, turning instead to cheap

luncheonettes. He describes one of their exchanges:

She was sitting at the table drinking coffee when I went in, the

battle hissing away on the stove, sending up jets of steam.

“Gee, but you slow this morning,” she said. “Take

some of that water in the kettle and go wash your face. Though

sleepy as you look, maybe you ought to just use cold water.”

“This’ll do,” I said flatly, feeling the steam

drifting upon my face, growing swiftly damp and gold. The clock

above the stove was slower than mine. (322)

The coffee steam offers neither warmth nor comfort as it instantly

turns cold. The fact that the clock on the stove is slower than

his own implies his feeling of entrapment and lack of progress

in his present state. Indeed, his ingestion of the coffee is no

better.

I took the cup and sipped it, black. It was bitter. She glanced

from me to the sugar bowl and back again.

“Guess I’ll have to get some better filters,”

she mused. “These I got just lets through the grounds along

with the coffee, the good with the bad. I don’t know though,

even with the best of filters you apt to find a ground or two

at the bottom of your cup.” (323)

Here, food is a metonym for racial struggle, as the coffee is

bitter. Ellison plays with the black and white imagery as the

protagonist rejects the white sugar, but acknowledges its need.

The coffee filters come to represent the protagonist’s inability

to distinguish good from bad, truth from fiction. Eventually,

the Invisible Man determines he cannot exist in any sort of socially

acceptable domestic space; it conflicts with his ultimately transient,

underground identity. He cannot coexist with gleaming kitchen

appliances or fruit cocktails, so he retreats entirely from its

culture and all it implies.

The navigation of the kitchen by the “Other” is also

present in Richard Wright’s Savage Holiday (1954),

in which the protagonist, Erskine Fowler, is a terminated insurance

claims adjuster—a sinister precursor to Tom Rath. In an

interview about the novel, Wright commented, “I picked a

white American businessman to attempt a demonstration about a

universal problem…the problem of freedom” (236). The

fact that Wright addresses the problem of freedom for whites draws

the reader in turn to question the problem of freedom for blacks,

the binary opposition present in the novel through absentia.

Wright characterizes Fowler repeatedly as an Other, implying that

he is not free. Like Bigger Thomas and Cross Damon, the protagonists

of Native Son and The Outsider, respectively,

Fowler finds himself an outsider in many ways, many of which are

linked to his domestic space. Though Fowler is not persecuted

because of his race, he is a foreigner in his own residence. Fowler’s

apartment building implies community, a microcosm. But Fowler

is out of place in his own home. Often described without clothes,

he immediately becomes a savage, uncivilized other. He is often

defined in contrast to light, whiteness and white spaces. “A

cascade of shimmering yellow light showers down from crystal chandeliers”

at an insurance dinner he attends (1). Fowler tries to retrieve

his newspaper and is trapped outside his apartment in the “sun-flooded”

(45), “brightly-lit hallway” (42). And as he cowers

nude against the wall, his dark, hairy body stands out against

the white background, “The hallway in which he stood was

white, smooth, and modern; it held not Gothic recesses, no Victorian

curves, no Byzantine incrustations in, or behind which, he could

hide” (45). The architectural forms alluded to are all dark,

or produce shadow. Fowler knows he can cower in darkness and not

be seen, implying that he is not white, but black. His murder

of Mabel occurs in his kitchen, which Wright clearly defines as

a white space: Mabel stands nude “amid the white refrigerator,

the white gas stove, the gleaming sink, the white topped table”

(214). The light exists in contrast to Fowler’s blackness.

It is also significant that the murder occurs in a spotless kitchen.

The room becomes violent, ominous, a testimonial to Fowler’s

demonization of the Mother.

A similarly ominous depiction of “other” domesticity

can be found in Grace Metalious’s Peyton Place (1955).

As Wini Breines observes regarding the presence of “dark

others” in the 1950s, “Otherness was of interest to

young white people and racial difference was part of the ‘other

fifties’ many of them sought” (7). Nellie Cross, presented

as an other through a combination of her dark skin and poverty,

labors in the Mackenzies’ kitchen, loses her mind there,

and ultimately commits suicide as a result:

Nellie Cross stepped away from the sink in the Mackenzie kitchen

and sat down on the floor…Her head, she felt, had grown

enormous, and she held it carefully on her neck so that it would

not fall off and break into pieces on the clean linoleum. She

leaned back against a cabinet, and it seemed perfectly natural

to her to sit calmly on the kitchen floor…resting her

feet which ached from standing too long in one place. (227)

Nellie rests on the kitchen floor rather than on a couch in the

living room, indicating her marginalized class status. The “clean

linoleum” renders her head dirty by contrast. Metalious

compares her head to errant tableware falling off the counter.

Likewise, when Constance Mackenzie returns to the house that evening,

the kitchen’s disarray represents Nellie:

There were plates, caked with dried egg yolk, sitting on the

table, and dirty dishes in the sink. The garbage had not been

taken out, and the glass coffee maker, still half full, sat

on one of the burners on the electric stove. "That damned

Nellie," muttered Constance angrily, forgetting all the

times when she had come home from work to find her house spotless.

(231)

Metalious aligns Nellie with stale coffee and day-old dirty plates,

in direct contrast to the “frosty cocktail shaker”

and cigarette that represent Constance. In Peyton Place, the

author problematizes maternity, femininity, and domesticity in

the context of small town, seemingly benign and traditional 1950s

America.

In 1958, Lorraine Hansberry offered a less ominous, more optimistic

portrayal of racial and class struggle in the play A Raisin

in the Sun, in which the principal action occurs in the kitchen

of a small apartment. The first scene between Walter and Ruth,

an exchange concerning life’s dreams and scrambled eggs,

recalls the stereotypical, separate (if crowded, here) male and

female spheres presented in The Catcher in the Rye. Walter

declares, “Man say to his woman: I got me a dream. His woman

say: Eat your eggs. Man say: I got to take hold of this here world,

baby! And a woman will say: Eat your eggs and go to work. Man

say: I gotta change my life, I’m choking to death, baby!

And his woman say—Your eggs is getting cold!” (3).

The dialog conveys the depressing monotony of their lives in close

quarters, what Ruth deems “this cramped little closet which

ain’t now or never was no kitchen” (49). Even the

dawning of a new day is bleak, as the majority of the play takes

place in the “cramped little closet.”

A tension exists between the domestic interior and its alternative.

Walter gambles away family savings in unsuccessful financial ventures

he hopes will result in a better home, while Beneatha discusses

the homeland—Africa—as superior. Each character dreams

of the potential of the world outside, but action is limited to

the apartment’s interior, with the focus on the meager kitchen.

As trapped as the family may seem to be, however, the sole natural

light in the apartment streams in through the kitchen window and

enables Mama’s plant, a metaphor for the family, to struggle

along. By the end of the play, the family has not only survived

on meager light but it has also been reinvigorated. They are optimistic

about the move to Clybourne Park to a new house, a new kitchen.

Far from representing 1950s conformity, this kitchen represents

upward mobility, civil rights, and resistance against racial injustice.

In many ways, the 1950s kitchen will perhaps always elicit images

of a stationary, immobile 1950s of white bread, baked beans, shrimp

gelatin concoctions, outdoor barbeques, cheerful cocktails, and

most of all, an appealingly aproned subservient, beautiful, and

maternal housewife. The philosophies of kitchens and domestic

space proclaimed by Wright and Levitt, the political weight of

kitchens advertised by Nixon in the Moscow Kitchen Debates, the

double entendre of “domestic,” and the representation

of kitchens and cookeries in period literature such as The

Catcher in the Rye, The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit,

Invisible Man, Savage Holiday, Peyton Place,

and A Raisin in the Sun speak for the Other

1950s not only in terms of the feminist movement and civil rights

activism, but in the pervasive undercurrents of rebellion, transgression,

and power.

Tracing the trajectory of kitchens both fictional and non- proves

useful in documenting the revolution of the Other Fifties. The

nostalgic idea of Jell-O mold and spam lovingly, blandly, and

happily served by the wife and mother every night does not do

justice to the upheaval, subversion, and contravention clearly

coming to a boil on private and public, personal and political

fronts. The top-loading dishwasher, the rectilinear fridge, and

the linoleum counter ultimately take on a greater semiotics of

the marginalized. Instead of sealing the supposedly atypical narratives

in Tupperware, they are brought to the table and served. Their

contents even touch and color other food, altering its appearance

and taste. Kitchens represented protection from the Cold War,

repression of the housewife, advertisement of democracy. However,

this kitchen, deemed so insular, was a remarkably effective space

for architects, developers, politicians, and writers interested

in exploding the canned formula of domesticity in the American

1950s.

Works Cited

Breines, Wini. “Postwar White Girls’ Dark Others.”

The Other Fifties: Interrogating

Midcentury American Icons. Ed. Joel Foreman. Chicago: U of

Illinois P, 1997.

Eisler, Benita. Private Lives: Men and Women of the Fifties.

New York: Franklin Watts, 1986.

Ellison, Ralph. The Invisible Man. New York: Vintage

International, 1952.

Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. New York: Vintage

International, 1963.

Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. Women and Economics. Boston:

Small, Maynard, & Co., 1898.

Halberstam, David. The Fifties. New York: Villard Books,

1993.

Hansberry, Lorraine. A Raisin in the Sun. New York: The

New American Library, 1958.

Harrison, Molly. The Kitchen in History. New York: Charles

Scribner’s Sons, 1972.

Heilbrun, Carolyn G. Women’s Lives: The View from the

Threshold. Toronto:

U of Toronto P, 1999.

Kaplan, Amy. “Homeland Insecurities: Transformations of

Language and Space.”

September 11 in History: A Watershed Moment? Ed. Mary

Dudziak.

Durham: Duke UP, 2003.

Lupton, Ellen. Mechanical Brides: Women and Machines from

Home to Office.

New York: Smithsonian Institution, 1993.

Medovoi, Leevom. “J.D. Salinger’s Paperpack Hero.”

The Other Fifties. Ed.

Joel Foreman. Chicago: U of Illinois P, 1997.

Marling, Karal Ann. As Seen on TV: The Visual Culture of Everyday

Life in the 1950s. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1994.

Metalious, Grace. Peyton Place. Boston: Northeastern

UP, 1956.

Plante, Ellen M. The American Kitchen 1700 to the Present.

NY: Facts on File, 1995.

Rosenbaum, Alvin. Building Usonia. Cambridge: MIT Press,

1986.

Salinger, J.D. The Catcher in the Rye. Boston: Little,

Brown, and Company, 1951.

Wilson, Sloan. The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit. New

York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1955.

Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream: A Social History of

Housing in America.

Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1981.

Wright, Richard. Savage Holiday. Jackson: UP of Mississippi,

1995.

Figure

1

Figure

1 Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3 Figure 4

Figure 4 Figure 5

Figure 5 Figure 6

Figure 6 Figure 7

Figure 7