|

It was the time of carhops; it was the time of doo-wop. It was the epoch of Elvis and Miles. It was the age of the atom bomb; it was the age of the bus boycott. It was the season of Sputnik and Salk. It was a time when World War II was behind us, and everything was before us, when Disneyland arrived, as did Pacific Ocean Park.

Disneyland and Pacific Ocean Park were both born in a burst of postwar optimism, corporate expansion, unprecedented working-class prosperity, and wide open Southern California real estate. Disneyland opened in the summer of 1955. Pacific Ocean Park was launched in 1958. But in less than a decade, the story arcs of the two parks diverged drastically, revealing two sides to the postwar boom and what came next.

Disneyland was conceived by Walt Disney as a permanent amusement park where families could enjoy the day together without the seedy elements of traveling carnivals. He purchased 160 acres in Anaheim, about 25 miles southeast of downtown Los Angeles, cleared away the orange and walnut groves, and constructed his Magic Kingdom.

Visits to Disneyland, then and now, begin on Main Street U.S.A., an idealized Midwest town inspired by Walt Disney’s boyhood in Marceline, Missouri. Main Street’s post office, barber shop, candy store, and horse-drawn carriage are all constructed to three-quarters scale. At the end of Main Street lies Sleeping Beauty’s Castle with its elaborate fairy-tale turrets lit up at night in princess pinks and purples. You walk through the castle to enter the main portion of the park. Here, radiating out from Central Plaza, are four themed realms: Fantasyland, Tomorrowland, Adventureland, and Frontierland.

In each themed realm, landscaping, costumes, live entertainment, and merchandise harmonize to produce an environment where visitors are completely immersed in the distinct theme. Most of the attractions relate to Disney’s popular cartoon characters and movies. Original rides included the Jungle Cruise, Mark Twain’s River Boat, The Mad Tea Party spinning cups, and Peter Pan’s Flight. And wherever you wander, you eventually encounter a live, big-headed Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, or Snow White ready for a hug and a photo op.

Disneyland was a hit from the start, inspiring other entrepreneurs to try their hand at this new breed of recreational entertainment.

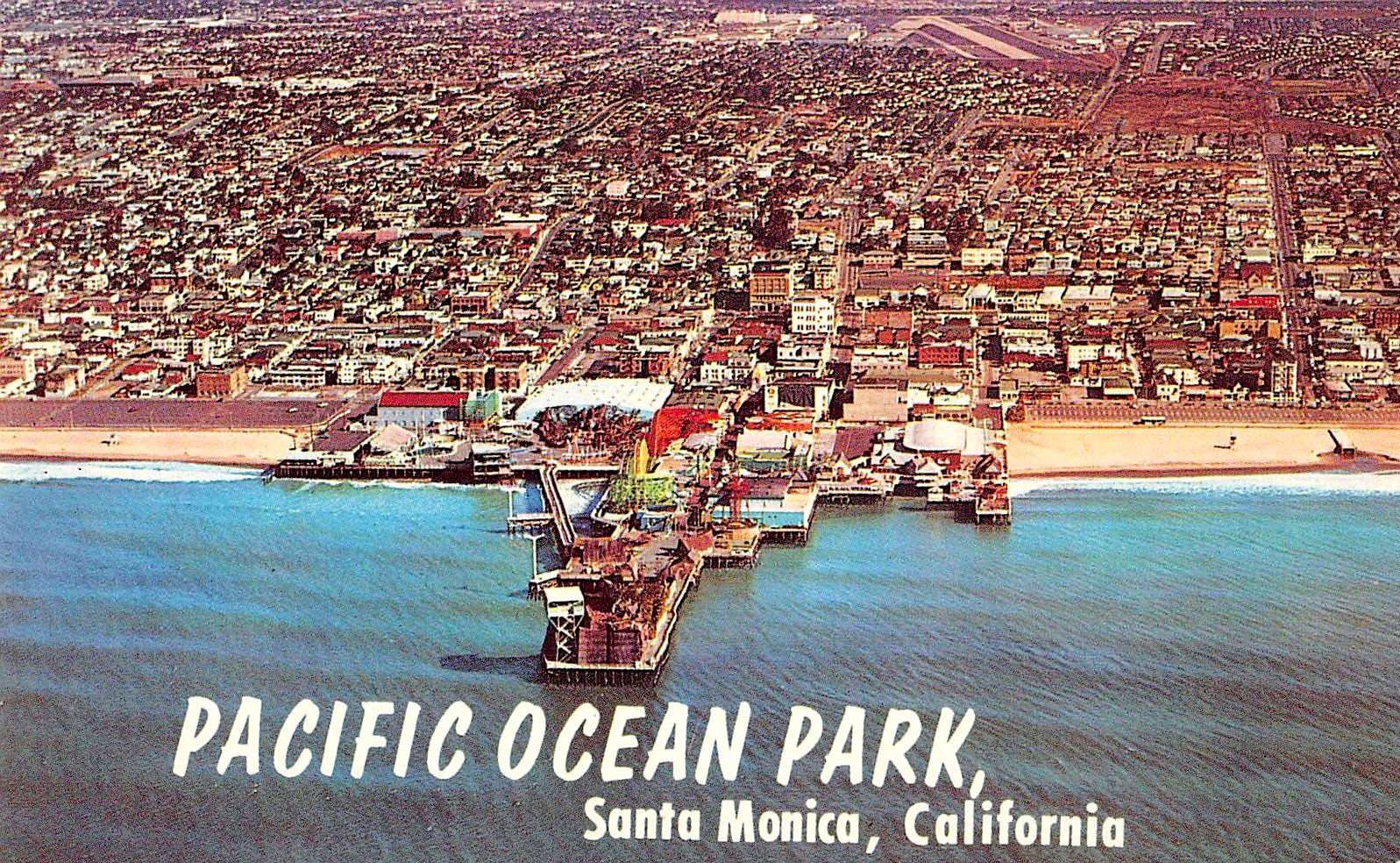

Pacific Ocean Park (known as P-O-P by locals) was envisioned by its creators as a kind of Disneyland-by-the-Sea. Stretched out along Santa Monica’s Ocean Park pier, P-O-P was an exhilarating medley of dark rides, roller coasters, fun houses, bumper cars, and midway games. Its entrance was styled in cool, sea-foam green art moderne. Clear, shallow pools of water surrounded the ticket booth which was set beneath a concrete starfish canopy festooned with frolicking sea horses.

You entered the park by descending in a submarine elevator to Neptune’s Kingdom — an eerie underwater world of motorized turtles, manta rays, and sharks — then emerged from the dark onto the sun-drenched Promenade. Amidst cotton candy sellers, shooting galleries, and ball toss games, were nautical-themed rides like Davy Jones’s Locker, the Flying Dutchman, Mystery Island Banana Train, and the Sea Serpent rollercoaster.

P-O-P opened the year I turned four. I remember it as being sunny and noisy and crowded, and smelling of corndogs and machine oil and salty sea air. I remember the crush of bodies on the promenade, me waist high to the grown-ups, looking up at bountiful puffs of pink cotton candy.

We lived only a few miles from P-O-P, and what I remember most clearly is being eleven or twelve, those pre-teen years when my friends and I were just old enough to be dropped off at P-O-P with a couple of dollars, and left there without adult supervision for the entire afternoon. Heaven.

Our favorite ride was the Whirlpool — a spinning centrifuge where the floor literally dropped away from beneath our feet. We entered the cylindrical Whirlpool room, racing to find a spot against the curved metal wall. Then we jockeyed for position, pressing our backs against the wall, stretching arms from side to side, shouting, and giggling — partly in nervous anticipation of the thrills to come, partly from the pure joy of hearing our voices bounce around the vast metal chamber. When the man high above pulled a lever, the machine noise started up, and the cylinder began to rotate, slowly at first, then faster and faster until we were pinned tightly back against the wall, which we knew was a good thing, an essential thing, because while there were poles to grab hold of, there were no seat belts or straps to hold us to the wall when inevitably, thrillingly, horrifyingly, the floor we were standing on dropped away like an anchor into the depths below. I wondered each time what would happen if I tried to pry myself away from the wall, maybe just extend a forearm or a foot into the gaping expanse before me. But my curious twelve-year-old mind also had a survival switch that told me not to tempt fate on the Whirlpool.

The other big thrill at P-O-P was meeting boys. Sometimes they’d just be there, fortuitously, on a parallel teen boy adventure. Other times we’d meet by design — our group of girls and their group of guys. We’d pair off for the Flying Dutchman, a dark ride with leering pirates, our boy-girl pairings accomplished through some mysterious (at least to me) teen decision making, probably a combination of pheromones and an unspoken attractiveness hierarchy.

Usually, someone brought along a couple of cigarettes, Newport Menthols stolen from Mom’s purse, Kents lifted from Dad’s coat pocket. We’d light up on the pier behind the Whirlpool, huddled together amidst the rumbling gears and pipes. We’d pass a single cigarette around, each taking a long drag, trying not to cough, practicing smoke rings on the exhale.

Eventually, the afternoon would wind down. Money would run out. The chilly ocean fog would move in. Parents had to be met. We tumbled into waiting cars and headed back home, tired and ready for the next moments of life.

Disneyland, on the other hand, was a wholesome family affair, which is exactly what Walt had in mind. Disneyland’s vibe was squeaky-clean, safe, family-friendly. No questionable food stands, no roughnecks running the fish-bowl toss. It was a place for birthdays, not dark ride make-out sessions. Our entire family, plus assorted friends, piled into the station wagon and drove across L.A. for what seemed like hours, we kids obsessing over our coveted “E” tickets and which rides we’d use them for. Then we’d wear ourselves out shrieking on the Matterhorn bobsleds, dashing across Tom Sawyer’s rope bridge, squealing on the dark, twisty Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride. It was always one of our favorite days of the year.

From opening day onward, visitors flocked to both Disneyland and P-O-P. Disneyland drew over one million visitors during its first year of operation. P-O-P recorded a whopping 20,000 customers on opening day and attracted over two million visitors its first year. Disneyland continued to sell tickets in gaudy, ever-increasing numbers: four million in 1956, six million in 1964, ten million in 1977, fourteen million in 1997…and so forth.

In 1967, however, the same year that Disneyland boasted eight million customers, an insolvent, crumbling P-O-P closed forever.

What happened? Why did this popular amusement-park-by-the-sea die an early death?

Geography played a key role. Disneyland was located near the intersection of two broad freeways, easily accessible to all of Southern California. P-O-P was situated in a seedy part of town. Winos accosted customers for spare change at the entrance. Rowdy local teenagers hung around at night, scaring off other customers. And the sea air was murder on the machinery. It’s expensive to run an amusement park, even more so with damp, salty, ocean breezes corroding the equipment night in and night out, month after month after month. Then there was P-O-P’s one-price admission, so much more affordable than Disney’s pay-as-you-play coupons, but it didn’t bring in enough revenue to cover costs.

P-O-P’s original owners, CBS and the Los Angeles Turf Club, eventually gave up and sold to a private investor. The park changed hands a few more times, but unlike Disney, nobody had pockets deep enough to maintain it properly. Broken rides went unfixed. Families began to stay away. P-O-P’s fate was sealed when the City of Santa Monica began an urban renewal project, temporarily closing off the main road to the park. Attendance dropped like the floor of the Whirlpool. Forced into bankruptcy, the park owners closed shop just nine years after opening.

As much as my friends and I loved P-O-P, I don’t remember feeling particularly sad or bereft at losing it. If I did, the feeling was short-lived. Maybe this reaction was because as young people we lived in the moment. Maybe it was because as a generation we were used to abrupt change, conditioned already to expect the unexpected. Presidents were shot; astronauts rocketed to the moon; amusement parks closed. It’s just what happened. And on top of all that, it was 1967, and in 1967 and my friends and I were obsessed with all things Beatles. We spent our weekends pouring over the images on the Sgt. Pepper album cover, debating the meaning of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” Sgt. Pepper, Surrealistic Pillow, and Alice’s Restaurant were wearing out our turntable needles. And other attractions — sex and pot and anti-war demonstrations — were just around the corner.

As the world changed, so did P-O-P. As the 1960s transitioned to the 1970s, the abandoned seaside amusement park morphed into a rotting beachfront leviathan. The pier’s crumbling foundation – splintered wood pillars and gnarled iron wreckage jutting from the sea – created the perfect playground for a bunch of scruffy local surfers. The dilapidated neighborhood around the pier became known as Dogtown and the surfers, sponsored by the Zephyr Surf Shop, became known as the Z-Boys. The Z-Boys went on to revolutionize the sport of skateboarding…as the P-O-P continued to decay.

I lived in Ocean Park/Dogtown in the early 1970s, often walking through the no man’s land around the rotting pier on my way to or from home. The concrete boardwalk was strewn with debris and broken glass. The ticket booth with the starfish canopy had become a graffiti-covered shooting gallery for junkies. The chain link fence around the remains of the park was always busted open. Sometimes at nightm we’d smell smoke and hear sirens rushing to a series of mysterious fires that further reduced P-O-P to a burnt-out shell of its former self. And all the while, ocean waves battered away at the foundations of the pier.

In 1974, the city tore down what was left of the Ocean Park pier. A sign stuck in the sand reading Danger – Possible Underwater Obstructions is today all that remains of the once marvelous and tacky Pacific Ocean Park.

If P-O-P’s demise was caused by the perfect storm of geography, urban renewal, and the vagaries of business at the margins, then Disneyland’s success has been one long, glorious spring of corporate-entertainment synergy.

In its sixty years of existence to date, Disneyland has had only three unplanned closures, three days that bowed to history. The park closed on November, 23,1963, to mourn the death of President Kennedy. It closed on September 11, 2001, as a precautionary measure. And, most interestingly, it closed on August 6, 1970.

In the summer of 1970, the Yippies announced their First International Yippie Pow-Wow…to be held at Disneyland. The Yippies were a youth-oriented, anti-authoritarian, counterculture group known for their outrageous, media-savvy actions. Paul Krassner, one of the group’s founders, called the Yippies, “an organic coalition of psychedelic hippies and political activists.” The Yippie flag featured a marijuana leaf superimposed on a red star.

Previous Yippie actions had included a mass be-in to levitate the Pentagon and an invasion of the New York Stock Exchange, forcing the NYSE to close by throwing hundreds of dollar bills down from the balcony. Two of their most famous members, Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, were at the center of the Chicago Conspiracy trial, charged with conspiracy and inciting a riot.

The Yippies announced that their Disneyland activities would include a Black Panther Breakfast at the Aunt Jemima concession, a liberation of Minnie Mouse from her male oppressors in Fantasyland, and a “smoke-in” on Tom Sawyer’s Island. Law enforcement took them seriously.

On the morning of August 6, expecting an invasion of 20,000 wild Yippies, hundreds of heavily armed police in riot gear massed on Disneyland’s Main Street. A visitor that day recalls, “I’ll never forget walking down Main Street and seeing it lined shoulder to shoulder with all those riot police holding Plexiglas shields and batons in front of them.”

Only about 300 Yippies showed up. But that was enough to cause a significant disturbance as Yippies romped through the park, chanting “Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh, NLF is gonna win!” A Disneyland supervisor remembers, “Word filtered down that the Yippies had taken over Tom Sawyer’s Island and had replaced the American flag with the Viet Cong flag…The police came out, the announcement was made that the park was closing and people were being asked to leave….All the supervisors were asked to report to their perimeter positions to safeguard the park from any Yippies who might climb the fence. We were actually given steel poles to bash fingers if they tried to climb the fence. I had a prime spot at the parking lot exit directly across the street from the hotel – lots of yelling, screaming, and tear gas.”

By 7pm, Disneyland had officially closed. It took a few more hours to flush out all the Yippies who had disobeyed the order to exit. Twenty-three people were arrested. A headline in the next day’s Los Angeles Times read: “Yippies Close Disneyland.”

More recently, Disneyland faced controversy around the revamping of the Its A Small World attraction. Built in 1963, the boats that carry visitors through exotic realms of singing children were designed for passengers who averaged 175 lbs per male and 135 lbs per female. Those numbers are outdated in today’s super-sized America where obesity has reached epidemic proportions. Many Disneyland guests weigh more than 200 pounds. Over-weighted boats were hitting bottom, getting stuck in their channel, and causing long delays – particularly annoying to customers already waiting in long lines for each attraction. Disney staff would tactfully guide a few passengers off the jammed boat, so the ride could resume. Those escorted off the boat were given free food coupons for their troubles.

It’s A Small World closed for ten months for renovations. Disney officials denied that the renovations were connected to passenger obesity, stating instead that the ride was simply due for routine repairs caused by years of use. When Small World re-opened, water channels were deeper and broader, boats wider. Now rumor has it that other Disneyland rides such as Pirates of the Caribbean will have to be revamped owing to the rise in passenger poundage.

Neither controversy, nor invasion, nor any economic slump has endangered Disneyland’s existence. Each decade brings in more customers, new attractions, additional Disney parks in faraway countries, even fresh low-cal food at some concessions.

Long gone P-O-P, on the other hand, now yields up the magic allure of a paradise lost. In today’s nostalgia laden culture, boosted by the internet, demolished theme parks don’t just die — they go to the big cyberspace market in the sky. P-O-P guidebooks, pendants, postcards, and sea serpent coffee mugs are all for sale on eBay. Each day the park is recycled, ticket stub by ticket stub, memory by memory.

While theme parks like Disneyland and P-O-P were new in their time, they have roots in earlier forms of outdoor recreation…and cast a significant and growing shadow over our present and future habits of consumption and tourism.

Since the Middle Ages, there have been amusement parks in Europe where the public could watch acrobatics, juggling, and freak shows, where they could play games and walk through exotic animal menageries. In nineteenth century America, there were picnic grounds with merry-go-rounds where working people could spend an inexpensive day relaxing, taking in a concert, swimming, eating, and drinking. Some picnic areas, known as “beer gardens,” were sponsored by local breweries as a way to sell directly to the public and cut out the middle man. Traveling carnivals, with their fire eaters, wild west shows, food vendors, games of chance, magic shows, ferris wheels, and animal acts have made their way across America since the 1800s. Setting up in an open field, moving on in a couple of days or weeks, carnivals had a reputation for danger and sleaze. Permanent amusement parks such as Coney Island took off in the early 1900s when Americans with some disposable income looked for new ways to spend their leisure time. Innovations in rollercoaster technology brought in more customers to experience new thrills. Semi-themed areas like Luna Park at Coney Island already existed, but it took Walt Disney’s vision, resources, and brand name recognition to create the first true and total theme park. As technologies, economies, and cultures have evolved, so have theme parks and their predecessors.

So what about the future? Can even a colossus like Disneyland survive in a digitizing culture where entertainment, and just about everything else, is going virtual? Can theme parks survive in a society where terrorism threatens public safety, where more and more people are staying home out of fear? Will theme parks morph into a new iteration of recreational entertainment fit for our new world?

Or perhaps that future is already here. But instead of theme parks changing to fit a new world, the world is becoming a giant theme park. Sometimes called Disneyfication, real places are being repackaged and “themed” into idealized, sanitized versions of themselves, fit for tourists and consumers. Think the French Quarter in New Orleans. Think San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf.

Disneyfication is the transformation of public space into a corporate-built environment. History, heritage, and geography are removed from social realities, stripped of any contemporary political relevance, and sold as an “experience.”

In Tibet, the Chinese government charges $5 for tourists to gawk at the sacred Tibetan rite of sky burials — feeding human corpses to a flock of vultures.

In Venice, Italy, the Rialto Bridge leads to shops selling miniature replicas of the Rialto Bridge.

In Mississippi, a tiny, impoverished hamlet, desperate for tourist dollars, fixes up an old ramshackle juke joint to resemble…an old ramshackle juke joint.

Universal CityWalk Hollywood, a three-block entertainment, dining, and shopping promenade, bulging with neon and security cameras, incorporates versions of iconic L.A. …minus the traffic, the crime, the unexpected.

Disneyfication is the creation of worlds cut off from the stresses of daily life, saturated with consumption opportunities, where the imaginary and the simulated and the real blend, bend and form something new, something postmodern.

Welcome to Theme Park Earth.

June 2016 From guest contributor Eve Goldberg

|