|

In my experiences during travel throughout both Western and

Eastern Europe, I am frequently asked questions about life

in the United States. Packed within many of the questions

are preconceived notions about what it means to live in the

US and what it is like to be an American. Almost consistently,

these perceptions categorize Americans as being similar or

exactly alike in their thinking.

Often European cultures do not recognize the regional differences

that comprise the different areas of the US When we cross

borders into different regions in Europe, we often find ourselves

exiting from one country and entering into another. The borders

and regions of the United States are decidedly different;

all regions use the same currency, speak the same language,

and share unencumbered borders.

The idea of small communities, regions, and towns is often

overlooked in American studies courses overseas. As Rob Kroes

in “The Small Town: Between Modernity and Post-Modernity”

discusses, American studies courses often focus on the big

city areas and broad regions of the United States and the

study of smaller communities and regions often gets marginalized.

Kroes asserts, “Currently themes like borderlands and

multiculturalism seem to carry everything before them. They

have become the buzzwords at learned gatherings of American

studies specialists, the signal codes for all those who are

interested in the de-centering of the American sense of self.”

What about regions and communities that do not exactly fit

into the current schemata? Kroes quotes Hollander who says,

“Community studies are still the best conceivable introduction

to the national culture of another country and it is a cause

for wonder that the study of America in Europe pays so little

attention to them.”

In American studies abroad, there are frequently recognitions

of the differences between the South and New England, for

instance, but when we closely examine how the regions of the

US are divided, there are marginalized regions that are often

dismissed or under taught within European and American colleges.

One such region in the United States is Appalachia.

In Appalachia Inside Out, Higgs, Manning and Miller

say, “We cannot define precisely where Appalachia begins

and ends geographically,” but the region usually includes

the mountainous regions of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Virginia, Kentucky,

Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina,

Mississippi and all of West Virginia. Statistics from the

US government and other sources often represent Appalachia

as behind in education, employment opportunities, and culture,

among others things. Even in American Studies programs in

the US, Appalachia is often not studied as a unique region.

Higgs et al., in their introduction to their Appalachian reader,

state, “Like the issues of gender and ethnicity, the

question of region has entered the debate over what constitutes

the canon of American, and even southern, literature. Appalachia

Inside Out engages this issue of region, which major

American literature texts, focusing as they usually do upon

major authors and literary movements, fail substantially to

address.” Once we study the region closely, the rich

cultural heritage and history of Appalachia make for a multi-faceted,

unique area that deserves consideration in American studies

courses both in the US and abroad.

Originally Appalachian settlers came from many European lands.

According to Higgs et al., the original settlers of the Appalachian

mountains were “already on the fringe of their original

culture, displaced by war, economic conditions, or ambition.”

Settlers were Scotch-Irish, British, and Native American.

Even today, most of the inhabitants of the region are Caucasian.

I was fortunate enough to live in the Appalachian region of

Virginia for six years. During that time, I taught in a small

Appalachian public high school, conducted research with Appalachian

women at two community colleges, and read multitudes of literature

from and about the region. What I discovered about the people

of Appalachia is that family ties closely bind them, families

are hesitant to leave the area, and the people of the region

have a deep pride in their cultural heritage.

As a high school teacher in Shawsville, Virginia, located

in the Montgomery County region of Southwest Virginia, I had

my first encounter working with Appalachian students. My charges

were eleventh grade English students, who comprised all levels

of literacy. Shawsville is one of the poorest areas of Montgomery

County, Virginia. When I was hired, the principal told me

that over fifty percent of the students lived in trailer parks.

What I discovered at my first teaching post in Appalachia

was that the students were painfully aware of the negative

stereotypes and assumptions that surrounded them as poor Appalachians.

Sadly, their perceptions were often truisms.

In American culture, the Appalachian people, often synonymous

with mountain people, are portrayed as ignorant, incestuous,

and wild. Television programs such as The Beverly Hillbillies

cement the negative perceptions and stereotypes into

the minds of Americans. Possibly the most damming and hurtful

stereotypes came from the 1972 film Deliverance.

In the film “mountain men” are portrayed as uneducated,

dirty, and rapists of tourists. Even as recently as this year,

a television commercial aired showing some men getting out

of an SUV in the mountains, and when they hear the song “Dueling

Banjos,” the “theme song” of the mountain

men in Deliverance, they run to the car and make

a quick exit.

With such negative media portrayals, my students expressed

their disdain for their dialect and their geographical ties

to Appalachia. They perceived themselves as unable to do much

with their lives since they would always be hindered by being

Appalachian. Bill Best, in his article about Appalachian culture

and custom, writes that “the combination of shame, emotional

sensitivity, and artistic forms of expression makes Appalachian

children poor candidates for success in the public schools,

where almost all such attributes are not valued and where

very few of their strengths are perceived as such.”

My students’ concerns became my concerns. I dedicated

the following five years and my dissertation research to unpacking

the mysteries of Appalachia. My interests led me to study

the industrialization of the Appalachian region and, specifically,

how the continuous closing of factories affected the economy

and, more importantly, the workers at those factories.

Appalachia has always been a desired region for large, manufacturing

companies because of the powerful rivers, the vast expanses

of land, timber, and coal, as well as an available, cost effective

workforce. Perhaps the most affected industry, due largely

to the North American Free Trade Agreement, was textile and

garment manufacturing. M. Mittelhauser says, “Employment

in these industries has been projected to decline by about

300,000 jobs over the 1994-2005 period, compared to a net

loss of about 250,00 jobs over the previous 11-year period.”

The statistics were startling, and I was particularly concerned

about what happened to the women who were previously employed

in the sewing industry.

In the fall of 2000, I decided to attend a community college

developmental writing class with the intention of finding

out about the progress of displaced garment workers who would

be taking this class. Instead of just collecting data about

writing instruction, I found myself gathering information

about women’s lives - women committed to their families

and their heritage in a way I had never witnessed in other

American cultures. The women who participated in my study

have overcome incredible odds and hardships; the mere fact

that they have found themselves in college for the first time

(at the ages between 23 and 50) is an incredible testament

to the dedication and will power that many of the women of

Appalachia possess.

During the time that I taught, researched, and lived in Appalachia,

I talked and studied with women who have made the study and

teaching of the region their life’s work. I discovered

authors like Barbara Kingsolver, who divides her time between

the American Southwest and Appalachia; Nikki Giovanni, who

as a Black feminist poet was born in and now again calls Appalachia

home; Sharyn McCrumb, who has penetrated the mainstream fiction

market; and Jo Carson, whose “found poetry” about

and from Appalachians gives a voice to people from the hills.

The rich tapestry of writers, musicians, and artists of the

region, in addition to the time that I spent with Appalachian

women, convinced me of the need to include Appalachian studies

in the American studies curriculum. Allison Ensor, in a discussion

of the importance of establishing a canon of Appalachian literature,

states, “Although I attended elementary school, high

school, and college in one of the Appalachian counties of

Tennessee, I heard virtually no indication from my teachers

that the literature - or the history or culture - of Appalachia

was of any importance at all.” Ensor, among other writers

and authors of the region, recognizes the tendency to ignore

Appalachia in the planning of American studies and literature

programs.

Once I left Appalachia and began teaching in New England,

I realized the study of the region did not often occur once

outside the region. Consequently, I created a critical writing

course that focuses on the history, culture, and literature

of Appalachia. Critical writing courses at my University are

sophomore level writing courses that focus on writing, researching,

and documentation. Each professor chooses a theme for his/her

course and the writing in the class revolves around that theme.

Within the course, I use the reader, Appalachia Inside

Out. We also read Jo Carson’s stories I Ain’t

Told Nobody Yet and a novel, Sharyn McCrumb’s The

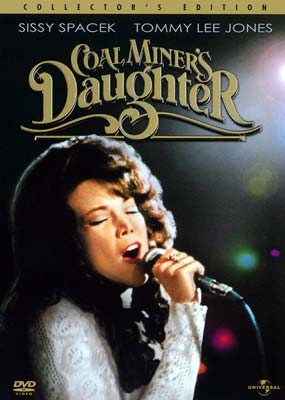

Ballad of Frankie Silver. Additionally, I use a film

from the 1980’s called The Coal Miner’s Daughter,

which as far as Hollywood presentations go, does surprisingly

little stereotyping about the Appalachian culture.

In the beginning of the course, I spend several days unpacking

the stereotypes that my students have internalized about Appalachia.

W. H. Ward cautions, “The main obstacle here, of course,

is an abiding one in a great deal of regional writing still

deeply tinged with local color: the tendency of characterization

to run stereotypes.” It is exactly this caution that

encourages me to dispel the stereotypical information that

my students bring with them to my course. At first, they are

reluctant to admit that they have any stereotypes, but once

we open the discussion and I am frank about my own preconceived

ideas from my childhood, they open up. At the age of a freshman

or sophomore in college, my students are significantly impacted

by the media and what they see and hear from its sources.

They hold all the common stereotypes about “mountain

men” - moonshiners, incestuous, poor, dirty, shoeless,

uneducated. What follows next in the course is an exploratory

essay in which students not only identify their preconceived

stereotypes but also dig to find where the stereotypes originated.

If you speak to any of the students that have completed my

Appalachian course, you will hear that they have a newly gained

respect for its people and culture. They probably can hum

you a few bars of a bluegrass song, tell you about their Appalachian

penpal who is not a barefoot, wild rapist, and tell you how

they think the legend of Frankie Silver is one in which Frankie

was wrongly convicted for killing her husband. It is in the

teaching of the Appalachian focused course that I have affirmed

my belief that the study of Appalachia belongs somewhere,

hopefully in American Studies courses, within the University

curriculum.

It is not my intention to think that we should “save”

Appalachians, but instead to celebrate and study their culture

to increase its cultural significance and our understanding.

If an already marginalized region becomes further marginalized

by not being recognized within college curriculums, then the

region will continue to be negatively impacted. I think often

of the high school students that I taught in Shawsville. I

hope that they are in universities where their culture and

literature are celebrated. I also think often about the women

with whom I studied at the community college. I hope that

through their writing and in their new positions that their

culture is as valued as they value it.

December 2004

From Katherine L. Hall, Assistant Professor of Writing Studies

at Roger Williams University

|