Throughout the history of pop music, there has always been an influential cultural icon for consumers to follow. In the following, my aim is to take a modern look at three various representations of these iconic models - of which all are melded and intertwined together as part of what constitutes pop music - and address their respective impacts on consumer culture both individually and holistically. In addition, by analyzing these icons from a modern, fragmented perspective, I hope to unveil to readers the effects pop music iconography continues to have on consumers and their methods of consumption and idolization. For my contextual purposes, I will be concentrating on the artist/s, album cover art, and modes of music collecting such as vinyl albums, CDs, and MP3 players.

Academicians often attempt to classify and label theoretical movements in a variety of ways. For us, "modernism" can be best defined by Chris Barker, who writes, “Modernism incorporates the tensions between on the one hand, fragmentation, instability and the ephemeral and, on the other hand, a concern for depth, meaning and universalism.” Two primary constructs I wish to focus on are fragmentation - which I will frequently refer to as individualism - and universalism - which will be synonymous with globalization.

Music Artist/s

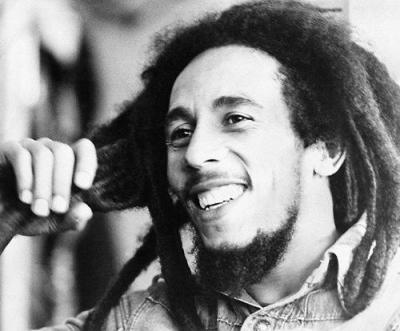

Of the numerous artists who can be considered when studying this idea of a "cultural icon," there is no better representative than Bob Marley. In this section, I will primarily use Marley’s legacy and impact, along with a few other popular names from the past fifty years, to support my claim.

Paul Gilroy writes of Bob Marley, “He has become an immortal, uncanny presence.” First, we must ask ourselves, “How and why is this so?” Marley, born in Jamaica to an Anglo-American father and a black mother, grew up during a turbulent time for his country. Gilroy explains, “Marley certainly endured a difficult childhood as what would now be called a ‘mixed race’ child. It introduced him not only to poverty and the viciousness of racial hierarchies, but to the antipathy and suspicion that can be directed from both sides of the colour line at people whose bodies carry the unsettling evidence of transgressive intimacy between black and white.” Due to the concept of being a "mixed race" child, Marley, early in life, began to strive for a unification and "oneness" amongst all people - this attempt to achieve harmony would carry over, not only into his music and lyrics, but to his image and messages, too. Gilroy furthers this idea by stating, “Contrary to the stereotype, mixed parentage does not seem to have been a handicap for him but rather to have conferred some interpretative advantages and stimulated him towards useful insights into the character and limits of identity and groupness.” Marley’s "mixed race" dualism directly coincided with his country’s consistent struggle and longing for independence from colonial Britain. Like Jamaica, sixties America was harboring its own share of political and racial unrest. Though the Civil Rights and Voting Acts had both been passed, the majority of blacks and whites were still at a high level of civil unrest, not to mention the presence of the Vietnam War and its lingering effects on the nation. All of this American instability did not go unnoticed by Marley, who, by this time, had moved to America to work as a housekeeper and since moved back to his home-nation.

During this time, Marley and his band mates became interested in the iconic messages that performers like James Brown were singing to audiences. As David Shumway writes, “Look magazine [asked] in its cover, ‘Is this the most important black man in America?’” In 1968, Shumway reminds us, Brown released his “Say It Loud - I’m Black and I’m Proud” which would, essentially, become the “anthem of the black-power movement.” With influential artists such as Brown frequenting the Jamaican radio waves, Marley began to write songs that would rebel against the cultural "normalities" of the time - for not only Jamaica and America, but all people. In a word, the music was anti-establishment. However, for Marley, it was not rebellion in the sense of an uprising anarchy; in contrast, it was the exact opposite. Of this, Gilroy writes, “Bob’s lyrics not only remind us of the goal involved in making the colour of skin no more significant tha[n] the colour of our eyes. They also admonish anybody who hesitates before the existential responsibility which comes with knowing that you do, contrary to appearances, rule your destiny.”

As Gilroy explains, “the underdeveloped world that made itself audible in the core of overdeveloped social and economic life” is referred to by Marley as "Babylon." In this light, Marley appears to be commenting on the world as being too "individualized" - and the shards and remnants remaining are only becoming more "fragmented" with time. To respond to this, Marley attempted to offer a counter to the disillusioned "Babylon"; he and the Wailers became the first true pop leaders of the "world music" movement. Through "world music," Gilroy writes, “The Jamaican rebel style was heard, copied and then blended into the local traditions of Brasil [sic], Surinam, Japan, Australia, and numerous African countries, particularly Zimbabwe, Zaire, South Africa and the Ivory Coast.” In a sense, Marley and his band mates were attempting globalization and unification by means of a rebellious method of peace, love, and awareness. By doing so, there was a hope that what had become a fragmented world could once again reach some sense of simplistic and cohesive understanding.

Marley’s work and efforts did not go unnoticed to the consumers of his time (and still to the present day). Setting aside the fact that Marley’s face - marked with wrinkles of struggle and shrouded in mists of ganja smoke - can be found on countless posters, the peace warrior’s message has effectively spread to seemingly all corners of the globe. Gilroy asks, “Do people connect themselves and their hopes with the mythic figure of Bob Marley as a man, as a Jamaican, a Caribbean, as African or pan-African artist?” This is a difficult question, and one I believe cannot have a simple answer. For our purposes, I believe consumers so intimately connected with Marley because of his melodic plea for a return to an Edenic paradise amidst the troubles and woes of war and racial conflagrations. Gilroy explains that Marley “[gave] post-colonial Jamaica a voice in the world” and created a “shift away from non-violence and towards legitimate force, deployed in self-defence [sic] [which was] registered in [his] imagination.” Shumway writes, “Music was the glue that held young people together, something shared that transcended any particular politics except that of youth itself.” Shumway is correct: People were tired of the disenfranchised "Babylon," and Bob Marley was the global rally cry who would let these people voice their concern.

Album Cover Art

Thus far, I have attempted to show the cultural impact that pop music icons have on consumers by analyzing and primarily focusing on the artist, individually. What we must also consider in this study are the tools that artists are equipped with to further provide their work with proper clarity and intended representation. In this case, one of the most prominent tools available - though its popularity appears to be waning with the rise of digital music (MP3 players such as iPods, which will be addressed later in the article) - to modern pop musicians is the album cover. By examining album cover art as another mode of iconography, I hope to show how these various forms of artistic expression can and do affect cultural consumers.

Peter Plagens calls the album cover a “veritable Sistine Chapel ceiling.” In other words, artists/musicians use the cover itself as a canvas, while the actual text and images on them becomes the palette. On this canvas, the artist has free reign to produce his vision and message as he sees fit to portray it. To better understand this idea, I turn to my primary focal point for this section. In his article “CD Cover Art as Cultural Literacy and Hip-hop Design in Brazil,” Derek Pardue comments on his time spent with Brazilian hip-hoppers - who represent a microcosm for all artists - and the importance of cover art for them. To begin, we read, “‘Marginal’ hip-hoppers use images to represent the outside world, which they limit for political reasons to the periferia, in a manner that they propose transforms that world and consequently transforms themselves as well.” As Pardue explains, periferia is to be understood as the “socio-geographical term which symbolizes São Paulo’s suburban spaces and Brazilian ideologies of race and class during 20th-century processes of urbanization.” In other words, for Pardue’s studied Brazilian hip-hoppers, the album cover becomes a way to comment on and relay meaning pertaining to racial and class issues of the homeland. Of course, looking at this on a global scale, I would argue the same could be said for any artist in any country - while songs and lyrical content provide an oral means of representation, album covers present a visual and written one.

According to Pardue, Brazilian hip-hop appears to be dividing itself into two categories: positive and marginal. Of these two classifications, we read, “‘Positive’ hip-hoppers often claim that they are able to ‘exchange information’, a quality held in high respect, better than ‘marginal’ hip-hoppers, because they keep up with not only US trends but what is happening in England, France, Germany, Chile, Cuba, Japan, and other hip-hop centers.” For us, this point suggests that marginalized hip-hoppers (or marginalized artists of any genre) are forced to be "out of the loop," so to speak. Because they are outside - be it due to socioeconomic status, living in (sub)urban slums, etc., these artists, as a result, are naturally more fragmented and individualistic. Granted, they can be unified within their own small subgroups, but they cannot connect on a universal and global scale like the "positive" artists can.

Being aware of this division amongst artists, the push for creative freedom and representation on album covers becomes all the more important for these Brazilian hip-hoppers. Three ways in which the musicians achieve this symbolism can be found via 1) perspective camera angles, 2) clarity of images, and 3) typography. Like Bob Marley’s reaction to "Babylon," BR - one of the groups Pardue followed during his time spent in Brazil - dubbed oppressive and unjust figures of society as the ‘system’; to further expand on this, Pardue relays what BR group members discussed while attempting to create a look for their album cover, writing, “We are a target. [The system] is like that … [Let’s] just use our eyes and we’ll be looking down on the [periferia]. It’s serious.” By using this downward camera angle, consumers see BR standing up and symbolically defeating the "system." In addition, BR members look serious in order to show their intention of sending a stern message of counter-reaction against unfair treatment. This realistic depiction of periferia makes BR look like rebel warriors, harkening back to the days of Marley; simultaneously, this message also cannot help but appeal to consumers who feel the same sense of disillusion.

The second means of album cover representation can be seen through the clarity of images used. Pardue notes, “They felt that the profile of BR was ‘in your face, straight up no funny stuff.’ And, this could be most effectively achieved with a photo 100% in sharp focus with defined color boundaries.” For BR, and for consumers, vivid, sharp images with a detailed focus - all contained within a set and defined boundary - touches on "realism." Ultimately, the blinders of society are removed, and there remains no protective film to guard the true essence of reality; prospective consumers are subjected to a visual illustration of "truth" as seen by musicians with the same view of the world as themselves. While BR effectively depicts this sense of realistic fragmentation in their work, I interject here to briefly present and discuss another form of cover art that contrasts Brazilian hip-hop reality - sixties altered state-of-consciousness.

If we are to consider sharp, clear images as "realism," then we must also understand that album covers of the exact opposite form - those with non-confining boundaries, numerous colors, and shrouds of smoke - stand to symbolize the anti-establishment and counter culture in their own way. Of course, this form rose to prominence during the turbulent events of the sixties. The Civil Rights Movement and Vietnam led, in part, to the creation of the "hippie" subculture. In a sense, hippies were crying the same plea and seeking the exact refuge as Bob Marley - that of a return to a more simple way of life in which all could co-exist; this wish found fulfillment on album covers of the 1960s. Sam Sutherland writes of these album covers, “Visual elements now drew from a sometimes literally mind-blowing pantheon of styles and influences, from psychedelic art to high fashion, elaborate logotypes to commercial illustrative styles cribbed from simpler, bygone times.” Sutherland brings a fine point to mind: people of today look back at the Boomer generation and wonder why drugs were so prevalent. I believe it was because people wished for an escape from reality, which, in and of itself, was too much for people to cope with. Thus they searched for mind-altering methods to return the nation (and world) to a more peaceful and unified time. Both BR’s and sixties album art symbolize similar messages: 1) Be it through sharp realism or mind-altering "shrouded-ness," both cultures were/are counter-establishment 2) Both represent the struggles going on during their time - be it the periferia or Vietnam and the Civil Rights Movement 3) Both modes of expression appealed to its respective consumer culture - "hippies" (and followers of the sort) and global hip-hoppers (or anyone feeling undermined and misrepresented by the "system.")

A third method of examining album art and its effects on consumer culture can be found by looking at the cover’s typography. Typography is defined by Merriam-Webster as “the style, arrangement, or appearance of printed letters on a page.” The format, size, and space between letters all indicate meaning for the creators. For example, Pardue writes, “When I asked about the typography, Sérgio remarked that the block lettering works in multiple ways to ‘combine’ with hip-hop. First, it links to [the system], because hip-hoppers recognize official, government signs as stenciled. Some associate stenciled lettering with institutional uniforms or large building signs.” In other words, hip-hoppers see block letters of serif and sans-serif format as symbolizing the empowered "system" they oppose. The appearance of these stenciled formats seems structured, confined to boundaries and rules, rigid, and are used as the accepted norm of written "system" communication. Pardue writes of this opposition toward the institution: “In Na Mira da Sociedade, designers Sérgio and Fanta cracked the stenciled lettering in the title as a visual reply to being the target of society. In the CD insert pages they continue this theme of visual opposition by literally shooting holes in the ‘system’ typography.”

Another typographical form musicians use to make their artistic statements is graffiti. The style and structure of graffiti is everything typical block font is not - thus, it still opposes the "system," yet does so in a slightly less aggressive manner. Pardue writes, “Graffiti artists visually mark and subsequently oppose the rules of public place.” Graffiti font typically consists of fat letters that are not restricted to boundaries - the form takes on a somewhat playful resistance with its typical usage of a wide variety of colors and other stylistic choices such as italics. In a sense, graffiti is distinct because it allows the musician to, once again, turn the album cover into a canvas for his or her artwork.

Like camera angles and clarity of images, various forms of typography all play an important role in establishing the artist’s message on the album cover. Cover art becomes an entity of its own - it unifies people through its cultural images and messages. The creation process, which takes place to produce album cover art, unites fragmented people and cultures; the final product, whatever form it may take, is certain to affect consumers in some fashion.

Methods of Collection

Up to this point, I have examined two types of cultural consumer icons: the artist and album cover art. Respectively, each topic has been, and in its own form continues to be, an icon. While this may be so, there is a third mode of iconography that, in the present day, I find to be most prevalent - the MP3 player. The MP3 player has become iconic with modern music. As a result of this, digitalizing music has, I argue, caused the following for consumers: 1) an alteration of methods of collection 2) a return to an individualized state-of-being 3) the creation of a positive shift in control and power in the consumer’s favor.

The format on which music is stored has changed with time and technological improvements - this change is unavoidable. From LP records of varying size and capacity and compact cassettes, to compact discs and now MP3 players, one aspect is for certain: music storage devices are becoming physically smaller in size while the actual amount of information the device can store is growing exponentially. This fact creates somewhat of an intriguing division among consumers, which I will be referring to as meaning - or what consumers associate with and connect to when they purchase music. In this light, meaning can be associated with collectors of music and general consumers, too. I argue that storage devices such as LPs, compact cassettes, and compact discs allow buyers to acquire and brandish a physical means of space. On the contrary, MP3 players store digitalized music that cannot necessarily be held and stored as part of a physical collection. This is not to say digital music cannot be part of a collection; on the contrary, I believe it instead becomes a spatial object within the digital storage device. In essence, it is part of a collection, but its owner cannot say, “Look at the shelves that line my home…these are my memories.” Thus, music collecting becomes altered somewhat. Some will prefer to point to the MP3 device and say this is collecting as well, but storing music digitally changes the traditional meaning of what collecting represents.

On this topic, David Beer recounts part of Walter Benjamin’s narrative which, though pertaining to books, can apply to the storage of music, too: "I am unpacking my library. Yes, I am…I must ask you to join me in the disorder of crates that have been wrenched open, the air saturated with the dust of wood, the floor covered with torn paper, to join me among piles of volumes that are seeing daylight again after two years of darkness, so that you may be ready to share with me a bit of the mood…what I am really concerned with is giving you some insight into the relationship of a book collector to his possessions, into collecting rather than collection." For Benjamin, it does not matter if the books have been untouched for years - it is the memories established and shared due to the process of physically collecting the books that are important. This collecting is Benjamin’s "meaning"…the books surround him as a part of the history of his consumer life - they help define who he is. The same can be said for music collecting. As I write, I look to my shelf beside me and consider all of the albums I have collected. While I do own an MP3 device, I still relish in having this physical collection, regardless of if I touch them for years or not. Beer writes, “Benjamin describes a complex relationship between the collector and his books that is not simply about the practice of reading but about the physicality, aesthetics, experience, and tactility of collecting. Benjamin’s collector is immersed in memoires and narratives through the connections made…with the physical properties of the book as a form of technological reproduction.” There is obviously a strong level of reciprocity between book and music collecting methods - they are one in the same, just of a different mode of text.

Beer challenges MP3 users by asking, “What are the consequences of leaving our collection constantly packed away on a hard-drive?” For our purposes, aside from the transition away from the traditional method of collecting (one which I believe devaluates the collecting experience), my main fear for the decision to digitally store music is that it will return consumers to a fragmented, individualized state-of-being. David Hadju wonders, “Is the album dying, or is it just passing into another plane of existence?” Antony Bruno echoes Beer and Hadju by adding, “Does album art have a place in the future of digital music?” (26). All three authors’ questions relay a similar theme: What will be the fate of the traditional methods of pop music consumer culture? I believe MP3 players, and even online file-sharing, will return consumers to an earlier period when the primary focus was placed on the song instead of the album. Hadju writes, “The first half-century of recorded music reinforced the pre-eminence of the song, largely because the recording capacity of a standard ten-inch 78 rpm record was only about three minutes.” During this time, an individual song was more important than a united album. As records gave way to albums, more of an emphasis was placed on the entire collection as a whole. Artists who had become accustomed to achieving fame and popularity based on hit singles were now required to focus on a consistently thorough and worthwhile album for consumers to purchase. Were artists not able to do this, their works were said to contain "filler" songs - material that would satisfy the required space on the album, but not necessarily be meaningful contributions for the consumer.

Where then does the MP3 player fit into this scenario? First, we must look at how digitalizing music - thus making it available for download on the internet - is allowing consumers to pick and choose what has meaning for them, individually. Instead of having to purchase an entire album on CD format, or waiting for the single to be released, consumers can simply go to iTunes and select the individual songs they prefer. Not only does this method of collection take us back to early recorded music when A and B-side singles were sold (thus allowing people to pick and choose), it also turns the pop music consumer population into a fragmented culture. Buyers are not all getting the same collective experience (from buying the same cohesive album), instead they are individually selecting what appeals to them most. The same can be said for Bruno’s album art destiny. He writes of cover art’s role in digitalized music: “Its primary purpose is to serve as icons when scrolling through vast music libraries on the computer or iPod.” In other words, even the symbolic album cover is becoming less important - its role has been reduced to simply helping consumers identify the individual songs by scrolling through the interface.

I briefly intervene here to address a contradictory point (there are more, I am sure) which I see could arise with my argument. Though I believe digitalizing music is fragmenting and separating consumers, I do see the possibility of the creation of what I shall call "individualistic globalization." In theory, these two terms are polar opposites - the former divides while the latter unites - but, by combining them, we create what I believe digital music may do to consumers: cause a digital global unification on an individual scale. To put it simply, people may, with regards to music, connect with one another on an international scale like never before seen, even though they are choosing to personally select individual songs that have meaning for them. MP3 players and digital downloads may then, in essence, globalize consumers, while doing so on an individual level.

As a result of being able to pick and choose individual songs over entire albums, there remains one final category I wish to discuss: the power shift from artist to consumer. To begin with, I wish to quote Hadju’s answer to his own question referenced above. He writes: "What we are witnessing, then, is not the death of the album, but something more intriguing: a transformation in the nature of its authorship. While professional recording artists are creating all the materials that end up on home-recorded CDs, the art of their assemblage - of selecting, compiling, and editing (or even altering the tracks electronically) - has shifted into the hands of the individual at home." What Hadju is referring to is the power shift that is occurring between producer and consumer due to the decision to make digitalized music downloadable. In a sense, the artist is no longer the album creator - the consumer is. Hadju adds, “It is only to be expected that blank compact discs for home recording outsell commercial releases today.” Why is this so? Because consumers are able to select individual songs of meaning to them and organize their own compilations. These created CDs can be shared amongst people (the same can be argued for mixed tapes, though as much individual customization was not available during its prime); personal touches such as typography and designs can be added to the blank cover of the disc; and, a certain level of power is bestowed upon the consumer because he can do with the songs what he likes. Hadju even goes so far as to interview his own daughter who, we are informed, owns over one hundred created discs. The daughter - a member of the "MP3 generation" and targeted audience of the developing digital consumer culture - makes a critical point when she states why she enjoys making her own CDs: “[We can] mix it up. [Music] is a mix. The music industry is obsessed with categories - hip-hop, rock, New Age.... Put different tracks together. They may get along.” This opinion only further reiterates that consumers are becoming fragmented due to picking and choosing music to download from the internet. Artists, while their music continues to be played and enjoyed, lose their creative powers to wield the album as an overall work; instead, consumers are left to produce their own fragmented albums to suit their individual tastes and meanings.

Conclusion

In this article, it has been my aim to take a modern approach with regards to pop music and three of its main icons. This form of iconography - individual in its analysis, yet united in its purpose - stands to show how time and culture has affected pop music and its consumers. Artists, album cover art, and methods of collection all play a vital role in the fragmentation and, at times, unification of people. Of course, the study of these three icons, while informative as I hope it has been, leaves us with yet-unanswered questions which only time and technology can answer. Will the role of the artist decline as more control is placed in the hands of the consumer? Will iPods and MP3 players completely diminish the popularity of the album? Will digitalized music become the "new traditional" method of collecting? Whatever these answers may hold and unveil, my hope is that readers will now better grasp a small portion of pop music’s past in order to better interpret, analyze, and understand its future.

May 2011

From guest contributor Jeremy Burris |