Despite benefiting from a dedicated readership and enduring academic attention, opinions on the literary merit of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road remain divisive. Suffering from association with dated countercultural ideals and a critical apparatus based on a self-deflating mythology of bohemian spontaneity, On the Road’s lasting literary value is often difficult to identify. Summarizing the popular narrative of On the Road’s authorship, Matt Theado states that “in twenty-one days in April [Kerouac] punched his typewriter keys onto the lengths of paper and produced a long unparagraphed strip of text that would define him as a writer and an American icon."

Purportedly fuelled by stimulant drugs and pea soup, Kerouac constructed a bohemian vision of On the Road’s authorship so persistent it rivals the novel’s fictional narrative in its fame. Portraying himself as a speed freak author employing avant-garde theories of “spontaneous" creation, Kerouac locates On the Road carefully within the bohemian landscape he and his Beat friends popularized in the 1950s. In doing so, Theado states, “the actual facts of the composition [of On the Road] were blurred by rumour, misstatement, and faulty memory, creating a nebulous chronicle that is mixed parts fact, yarn, and legend about the distinctive characteristics of the scroll typescript, the subsequent typescripts that were produced from it, and the whole journey from inception to publication of one of America’s greatest novels."

Considering the fact that critical disdain of On the Road often fixates on the “blurred facts" of the text’s “spontaneous" composition, it is necessary to dismantle the countercultural aura surrounding both Kerouac and his text if an attempt is to be made to find reason for the novel’s longevity in American popular consciousness. This essay outlines an effort to dismantle the accepted portrait of Kerouac as pure bohemian in favor of a more accurate account of the material realities of Kerouac’s life. In doing so, I gesture towards new ways of approaching Kerouac and his writing, approaches that consider Kerouac’s text according to its content and Kerouac according to the material realities of his text’s authorship.

Inextricably tied to its context in the 1940s and 1950s, Kerouac’s writing is locked within the social mores of cold war America, a war which Michael Davidson explains “was fought out as much on the cultural as well as on the diplomatic front through collusions between federal agencies like the CIA and universities, literary magazines, arts organizations, public forums, and art studies programs. If there was a single ideology to the cold war cultural front it was the idea that...we had come to the ‘end of ideology’ and that the arts had to remain a bastion of aesthetic free enterprise against totalitarian censorship."

Recalling Michel Foucault’s theory of heterotopia, in which a subject’s perception of a space is determined by the differing spaces against which it is compared, the portrayal of On the Road as a heterotopic countercultural space seems tailored to position Kerouac’s novel on the front lines of the cultural war against the socio-political climate of 1950s America that Davidson describes. The “experimental" nature of Kerouac’s spontaneous aesthetic technique suggests On the Road was written as a direct challenge to hegemonic American social structures. Ann Charters writes that “in On the Road Kerouac had supposedly defined a new generation, and he was besieged with questions about the life-style he had described in his novel. The reporters didn’t care who he was, or how long he’d been working on his book, or what he was trying to do as a writer."

By recognizing the counterculture’s enthusiastic embrace of On the Road, it becomes clear that the text’s portrait of a countercultural space different from the hegemonic norm allows the novel to serve a social function far beyond anything inherent in the novel’s actual content. After all, along with Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl," Kerouac’s novel is often cited as one of the fundamental texts of the 1950s counterculture, a fact which continues to dominate the majority of discussions about the text. Indeed, despite its historical specificity as a countercultural document of the 1950s, the novel remains popular with audiences interested in contemporary counterculture. In an effort to understand readers’ enduring interest in the novel, I believe it is necessary to unpack the reality of On The Road’s authorship in contrast with its popular mythology. In doing so, Kerouac’s novel reveals a style and character more conventional than the text’s mythology presents itself as, but no less interesting.

Speaking generally of the Beats but with Kerouac in mind, portraits of the Beats frequently depict them as desiring an escape from the oppression of mainstream America, ironically often by means of fame and success as popular authors and artists. According to Davidson, the Beats either “resisted hegemonic American values, remaining outside the mainstream by refusing its terms (conformism, consensus, contract) or else, given the totalizing nature of postwar capitalism, they were assimilated into it." Many conservative critics of the 1950s, Davidson states, “liked to point out the similarities between Kerouac and company and the middle class, suburban society they excoriated." Instead of “rejecting the cultural mainstream, the Beats embraced many of its more oppositional features. Kerouac’s affection for Krazy Kat and the Marx Brothers, his love of fast cars and speed, his enthusiasm for all night diners and automats, and his belief in the lumpen underclass certainly invoke one vision of [the] American mainstream." Mainstream America always already exists in the works of the Beat counter culture. When Kerouac “rejects" American hegemony in On the Road,he does so with aspirations of fame in mind.

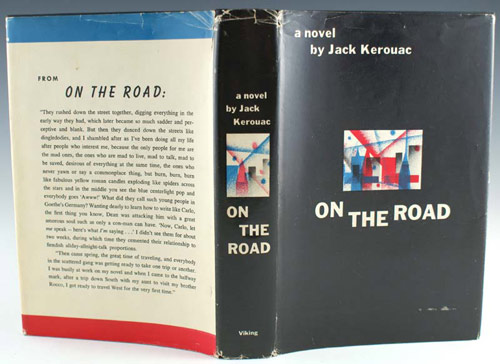

The romantic mythology of Kerouac’s artistically pure authorial intentions and creative process is secured when readers ignore Kerouac’s pursuit of fame in favor of his constructed identity as a bohemian. Returning to On the Road’s famed authorship, the myth reported by Ann Charters is that Kerouac’s wife, Joan, “fed Jack pea soup and coffee [while he wrote On the Road]; he took Benzedrine to stay awake. Joan was impressed by the fact that Jack sweated so profusely while writing On the Road that he went through several T-shirts a day. He hung the damp shirts all over the apartment so they could dry." Charters’ account of Kerouac writing the original scroll draft of On the Road casts him as an impassioned artist so enthralled with his work he could not sleep, let alone eat. Later, when On the Road was ready for publication, Davidson reminds us, “the manuscript of [the novel] finally accepted by [Viking Press literary advisor] Malcolm Cowley was a considerably edited and reworked version of the famous teletype roll."

By drawing a distinction between the artistically pure original scroll and the edited version of the novel Viking Press eventually published, Kerouac is painted as an outsider victim of the creative industries whose artistic intentions are compromised during the editorial process. Sympathetic scholars have apologized for Kerouac’s apparent creative concessions in publication, Davidson notes that “none of this disqualifies Kerouac’s remarks on spontaneity in prose; it simply points out certain discrepancies between theory and practice that are inevitable with a poetics dominated by such an expressive ideal." When the “spontaneous" creation of On the Road is used as a means of quantifying Kerouac’s success as an author, Kerouac’s work and persona serve only to reinforce the public’s popular conception of him as an icon of the experimental underground. However, the material realities of Kerouac’s authorship reveal Kerouac deserves no such distinction.

Before outlining the material realities of Kerouac’s authorship, however, it is necessary first to theorize the way Kerouac’s bohemian identity fundamentally informs the reception of his texts. Michel Foucault’s "author function" concept explains that despite the author’s apparent disappearance from the actual content of narrative, the author maintains a privileged position in relation to his or her text as a result of the association of his or her name with the work in question. That said, the author’s name does not represent the content of the text. Rather, the name signifies the whole of the author’s body of work for the reader, standing as evidence of what the reader can expect within a text by its association with past works inscribed with the same author’s name.

There is, according to Foucault, no concrete connection between the author function of the author’s name and the person with whom the name is materially associated. On the contrary, the author function is isolated from the person of the author, a construction beyond the author’s control. According to Charters, Kerouac’s author function positions the biography of On the Road as Kerouac’s “true subject - the story of his own search for a place as an outsider in America." As a result, when Kerouac’s author function is assembled according to the bohemian mythology of the Beats and of On the Road’s creation, the realities of Kerouac and of what Kerouac brings to his novel are pushed aside by both his readers and critics alike.

As mentioned earlier, Foucault’s 1967 lecture “Of Other Spaces" outlines the concept of “heterotopia." Speaking of spaces, Foucault explains that “the space which today appears to form the horizon of our concerns, our theory, our systems, is not an innovation; space itself has a history in the Western experience, and it is not possible to disregard the fatal intersection of time with space." Through the comparison of two different spaces, the subject constructs difference between the spaces. The difference between spaces allows the subject to relate to or occupy a space in time: “our epoch is one in which space takes for us the form of relations among sites." Spaces both define and enable modern society. With this in mind, Foucault introduces heterotopias, spaces that are “absolutely different from all the sites that they reflect and speak about." Heterotopic populations are “deviant in relation to the required mean or norm." More importantly, “the heterotopia is capable of juxtaposing in a single real place several spaces, several sites that are in themselves incompatible." For Kerouac’s audience, On the Road is a heterotopic space, a gateway to the alluring life of American bohemia. It suggests a vision of America attempting to escape the oppressive weight of the cold war, of modernity, of America itself. In its most idealized form, the heterotopia of On the Road, Foucault would argue, “creates a space of illusion that exposes every real space, all the sites inside of which life is partitioned, as still more illusory."

True to the heterotopia described by On the Road, Kerouac often did lead a bohemian life and his novels do work to capture its details. Indeed, just as On the Road finds Kerouac (or his narrator, depending on the edition) leading an unconventional life of hitchhiking, drugs, and lumpen camaraderie, in 1944, Charters reports, Kerouac “took so many drugs with [his bohemian friends] that finally his health began to suffer, and he was hospitalized after an attack of phlebitis brought on by excessive Benzedrine use." Kerouac’s lifestyle recalls that of Walter Benjamin’s Parisian bohemian, who would spend his days “on the boulevard, [where] he kept himself in readiness for the next incident, witticism, or rumor. There he unfolded the full drapery of his connections with colleagues and men-about-town, and he was as much dependent on their results as the cocottes were on their disguises. On the boulevards he spent his hours in idleness, which he displayed before people as part of his working hours...In view of the protracted periods of idleness which in the eyes of the public were necessary for the realization of his own labor power, its value became almost fantastic." Bohemia is a space of idleness. As Benjamin asserts, such idleness is a superficial facade for “men of letters." Kerouac’s wanderings and presence in the street are key to his participation in the bohemian tradition.

Kerouac spent lengthy periods travelling and bumming. In classic bohemian form, street life served as inspiration for his art. However, as the realities of Kerouac’s life reveal, the illusory, bohemian heterotopia of On the Road’s authorship never truly existed: Kerouac did not write On the Road in an impassioned marathon of speed and pea soup; rather, much of the novel was written in the comfort of his mother’s house enjoying the benefits of her home cooking. Theado writes that “Gabrielle Kerouac’s apartment was a model of decent middle-class life, a dominion she ruled over while providing cooking, cleaning, and nurturance for her son when he was not on the road or in the city. In the small living room, cushioned chairs were arranged around the television, and even Kerouac’s writing desk was positioned so that he could swivel his chair to see the TV."

Similarly, the apartment Kerouac shared with his wife during the writing of the scroll manuscript was surprisingly typical considering Kerouac’s bohemian pedigree. Theado writes, "For a time, the newly wed couple lived the reasonably calm and harmonious life that Kerouac had long pined for...Friends who rang them up at Chelsea 2-9615 or just dropped by their apartment were pleasantly surprised by the domestic tranquility. Joan found a better waitressing job at The Brass Rail, and Kerouac supplemented their income by writing movie script synopses for Twentieth Century Fox."

While Kerouac was publicly a man of the street, his home life did not differ much from that of middle class America. Like the Parisian bohemians, Kerouac’s writing, as Benjamin phrases it, “supported the oppressed, though it espoused not only their cause but their illusions as well. It had an ear for the songs of the revolution and also for the ‘higher voice’ which spoke from the drumroll of the executions." Kerouac’s voice certainly sits well with the lumpen bohemians, echoing his travels and street life. However, the domesticity of his private life locates his voice within the bourgeois middle class. This contradiction does not suit the purposes of Kerouac’s bohemian author function, complicating the mythology of On the Road by stripping it of its romance and danger. Kerouac’s place in the middle class is too familiar for his countercultural audience. As such, it is a reality often ignored by his readers.

Kerouac makes fleeting reference to the conditions of his home life in On the Road. In the edited 1957 Viking Press edition of the novel, the text opens with Sal Paradise in “Paterson, New Jersey, where I was living with my aunt." The narrative glosses over the domesticity of the scene, explaining Paradise’s reasons for living with his “aunt" by alluding to both divorce and studies: “I first met Dean not long after my wife and I split up"; “He came right out to Paterson...one night while I was studying." The text works to maintain the narrator’s countercultural authenticity despite his domestic comforts.

The scroll manuscript complicates this sense of authenticity when it reveals that Paradise’s “aunt" is in fact Kerouac’s mother - Kerouac writes that when Neal visits him at home “we went out to have a few beers because we couldn’t talk like we wanted to in front of my mother." Similarly, Paradise’s “divorce" stands in for the death of Kerouac’s father - “I first met Neal not long after my father died" - while “studying" is less specifically described as Kerouac working on “my book or my painting or whatever you want." Kerouac downplays the ties between him, his mother’s house, and his art by twisting the facts presented in his novel.

Likewise, Paradise recalls “one night when Dean ate supper at my house...he leaned over my shoulder as I typed rapidly away." Given the degree to which On the Road is steeped in autobiography, Kerouac’s self-mythologizing is in full effect here. It is well documented by Theado that “even in his youth, Kerouac was an excellent typist; he possessed an almost athletic prowess for typing." According to Theado, typing was a passion from which Kerouac drew great satisfaction as he watched “the neat lines of print on a growing stack of pages." With this fact in mind, it is unsurprising typing makes such an early appearance in On the Road. However, knowing that Dean ate supper served by Kerouac’s mother in the comforts of her suburban home before observing Kerouac’s skills as a typist - and thus as an of author of spontaneous prose - undermines the countercultural credit earned by Kerouac’s creative bravado. That Kerouac boasts of his creative process in his text while working to hide the comfortable nature of his environment indicates how actively On the Road invests in its mythic reputation.

Considering that On the Road actively participates in mythologizing itself, it follows that, as R.J. Ellis claims, “different On the Roads will exist in different readers’ cultural imaginaries. But these differences are complicated in the case of On the Road by different degrees of knowledge about the novel." Kerouac’s mythology falls apart the more readers learn about the novel; after all, the middle class realities of Kerouac’s creative environment indicate that On the Road’s mythology is misleading. As such, the text takes efforts to bury the realities of its authorship. That said, the original scroll of On the Road is, by its seemingly unedited nature, accepted as a more truthful account of Kerouac and his travels. However, like the Viking Press edition of the novel published in 1957, the scroll’s authenticity is similarly constructed, and thus it too can be dismantled by closely observing the process of its drafting.

Contrary to the belief that On the Road is largely an unedited novel - it is often cited as a manifestation of Allen Ginsberg’s mantra “first thought, best thought" - it nonetheless underwent a number of drafts and rewrites, even in its scroll form. Indeed, as Ellis tells us, Kerouac “widely complained about his publisher’s comment that a continuous scroll would be difficult to revise - something he did not want to do (particularly because he believed his first novel, The Town and the City [1950], had suffered from his publisher’s revision demands). Soon he was widely discussing how he was, after all, rewriting On the Road."

Though Kerouac started On the Road with the scroll manuscript, the journey leading to its ultimate publication takes the novel through countless changes; the process of the novel’s revisions was so extensive that Kerouac ended up producing two separate novels in addition to the On the Road released in 1957 - Excerpts from Visions of Cody (1959) and Visions of Cody (1972). By viewing the novel’s evolution, Ellis states, the 1957 edition of On the Road - the same edition celebrated for its heterotopic value - “emerges as carefully - even traditionally - structured." Consequently, the spontaneity of On the Road’s authorship is called into question, jeopardizing the novel’s countercultural authenticity by challenging the experimental elements of the text which serve as the best signifiers of its avant-garde status.

Though recognition of On the Road as a carefully structured text debunks the novel’s avant-garde claims and compromises its popular identity as a countercultural document, the novel’s structural choices are a surprisingly fruitful site of analysis for readers considering how carefully Kerouac and his publishers worked to obscure the text’s organization. Indeed, considering the efforts the text makes to mimic spontaneity, the novel’s careful structure reveals On the Road as a work of surprising complexity, the text’s organizational choices emerging as its biggest signifiers of thematic development.

An example of On the Road’s structure emphasizing its thematic complexity is found in the way the scroll ends as compared to “Part Five" of the edited Viking Press edition of the novel. Stretching only five pages, “Part Five" is very deliberately set apart from the rest of the text as an epilogue. Considering the novelty of its separation from the rest of the text, such a division exists to direct the reader’s gaze. By clearly isolating the section from “Part Four," a concrete thematic statement is made more obvious to the reader. The final paragraph of the edited Viking Press version of the novel reads: "So in America when the sun goes down and I sit on the old broken-down river pier watching the long, long skies over New Jersey and sense all that raw land that rolls in one unbelievable huge bulge over to the West Coast, all that road going, all the people dreaming in the immensity of it, and in Iowa I know by now the children must be crying in the land where they let the children cry, and tonight the stars’ll be out and don’t you know that God is Pooh Bear? the evening star must be drooping and shedding her sparkler dims on the prairie, which is just before the coming of complete night that blesses the earth, darkness all rivers, cups the peaks and folds the final shore in, and nobody, nobody knows what’s going to happen to anybody besides the forlorn rags of growing old, I think of Dean Moriarty, I even think of Old Dean Moriarty the father we never found, I think of Dean Moriarty."

Though the same passage appears in the scroll manuscript - the only significant difference between the two is the addition in the edited version of the non-sensical statement that “God is Pooh Bear" - the structural division imposed upon the text during the editing process sets these words apart from the seemingly “organic" flow of the narrative, forcing a thematic weight on to the section’s words as a result of their being separated from the rest of the novel. When the entirety of “Part Five" is read with its paragraphing in mind, the symbolic weight of Sal’s loss of Dean is drawn acutely to the attention of the reader, encouraging readers to dig through the complete events of the novel to construct a portrait of what Dean and the narrative mean to Sal, and by extension to America as a whole. As a result, the journey of Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty is granted a more obvious significance than is demonstrated by the free-flowing single paragraph of the scroll manuscript, the aesthetic sameness of the unparagraphed manuscript allowing fewer passages to assume obviously heightened degrees of thematic importance.

Contrary to the way On the Road’s mythology qualifies its success according to the terms of its “spontaneous" aesthetic, the material realities of On the Road’s authorship and its carefully constructed structure are exactly what enable the text’s success. Constructing a readership based on a false identity of countercultural authenticity, On the Road relies on a bohemian fantasy for its reception, a fantasy that the text is not equipped to grapple with due to its author’s middle class existence and the narrative’s meticulous mythologizing. As such, readers must unlearn their preconceived notions of “Jack Kerouac" as an artistically well-intentioned bohemian, replacing him with a more historically specific account of the material circumstances of On the Road’s creation and extensive drafting. In doing so, the existing legacy of Kerouac’s novel is explained while its shelf life is extended into the future, encouraging critics to put newfound critical pressure on the novel’s content and thematic structure without the baggage of Kerouac’s constructed bohemian identity.

July 2014

From guest contributor Robert Mousseau

|